The integration of negative affect, pain and cognitive control in the cingulate cortex is a recently published review, which raises some interesting ideas [1].

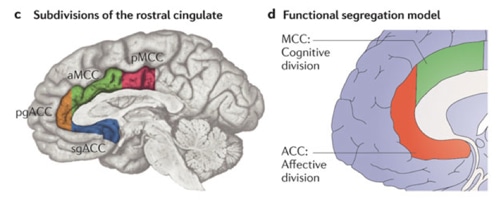

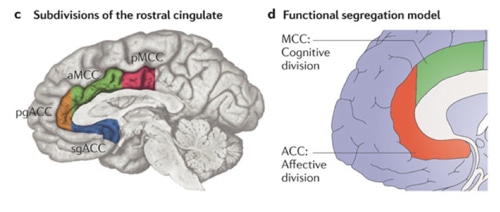

The best place to start is with a bit of neuroanatomy…if you were to cut your brain straight down the middle into two hemispheres and check out the medial surface of both hemispheres you’d see the cingulate cortex encircling the corpus callosum. We are particularly interested in the front bit: the rostral cingulate.

For a while now, a segregationist model has dominated most of the discussion relating to the function of the rostral cingulate. Lots of folks argue that the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is specialised for affective processes, and the midcingulate cortex (MCC) for cognitive processes.

This Review argues against this functional segregationist model, instead presenting us with lots of compelling evidence for the rostral cingulate—and they focus on the anterior MCC, or aMCC—as a “domain-general” processing area that is integral to negative affect, pain and cognitive control. (Note that cognitive control here refers to a range of processes, like inhibition, learning or attention that we engage when habitual or reflexive actions are insufficient). Here’s some of their arguments:

Evidence from functional imaging:

This Review collated results from more than 3000 subjects who participated in separate functional imaging studies investigating negative affect, pain and cognitive control domains. A conjunction map derived from these data reveals a sizeable cluster of activation in the aMCC, giving us physiological and anatomical proof of co-localisation of these domains in the rostral cingulate cortex.

Anatomical evidence of integration:

Invasive tracing studies performed in monkeys have told us a bit about the connections to and from the aMCC, in turn telling us a bit about the aMCC’s role. For instance the spinothalamic tract targets the aMCC, making the latter a hub for incoming nociceptive information [2]. And the aMCC projects directly to motor centres responsible for facial expression and coordination of other aversely-motivated behaviours [3].

These authors present –in my opinion—a pretty plausible working hypothesis as to why the aMCC makes a similar functional contribution to the three domains of negative affect, pain and cognitive control: negative affect and pain tend to engage the processes that come under the ‘cognitive control’ banner. Underlying pain and some forms of negative affect like fear and anxiety, is the need to exercise control and determine an optimal course of action in times of uncertainty. For all these reasons, the authors present us with the term adaptive control as opposed to cognitive control, to emphasise the role of the aMCC in controlling aversively-motivated behaviours.

As in any review, some limitations of the available evidence are brought up. Higher-resolution imaging of the rostral cingulate will give us a better idea as to the true degree of overlap in activation with negative affect, pain and cognitive control. But better resolution is afforded by imaging a smaller brain area. And findings in the cingulate cortex are only really interesting when they’re interpreted alongside all the other bits lighting up in the brain.

The adaptive control hypothesis is compelling, as is the evidence pointing towards the cingulate cortex as an integrated ‘hub’ in emotion, pain and cognitive control. The challenge now lies in interpreting and better understanding this region’s contribution to health problems like depression and chronic pain.

About Flavia

Flavia Di Pietro is a PhD student in the Moseley Group investigating the development of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) after wrist fracture. Flavia’s PhD focuses on the early detection of brain changes in CRPS using fMRI. But get this – Flavia did Physiotherapy Honours degree at Notre Dame and completely cleaned up – Brian Edwards Memorial Award, Physio Research Foundation Award, Dean’s Award. Now, these things mean that she is not only ticking the academic boxes but all the other fluffy stuff too. No surprises that the Australian Government jumped to support her PhD. So she has come over from Perth where she has been working as a physiotherapist. All her achievements, however, pale in comparison to her celebrated status as the best Shoe Salesperson south of Milano, as evidenced by her taking out the 2006 and 2008 Diana Ferrari Golden Boot Award. Clearly, she did not write this bio.

Flavia Di Pietro is a PhD student in the Moseley Group investigating the development of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) after wrist fracture. Flavia’s PhD focuses on the early detection of brain changes in CRPS using fMRI. But get this – Flavia did Physiotherapy Honours degree at Notre Dame and completely cleaned up – Brian Edwards Memorial Award, Physio Research Foundation Award, Dean’s Award. Now, these things mean that she is not only ticking the academic boxes but all the other fluffy stuff too. No surprises that the Australian Government jumped to support her PhD. So she has come over from Perth where she has been working as a physiotherapist. All her achievements, however, pale in comparison to her celebrated status as the best Shoe Salesperson south of Milano, as evidenced by her taking out the 2006 and 2008 Diana Ferrari Golden Boot Award. Clearly, she did not write this bio.

* One of the awards in Flavia’s bio is fictitious.

References

[1] Shackman AJ, Salomons TV, Slagter HA, Fox AS, Winter JJ, & Davidson RJ (2011). The integration of negative affect, pain and cognitive control in the cingulate cortex. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 12 (3), 154-67 PMID: 21331082

[2] Dum RP, Levinthal DJ, & Strick PL (2009). The spinothalamic system targets motor and sensory areas in the cerebral cortex of monkeys. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 29 (45), 14223-35 PMID: 19906970

[3] Kanske P, Heissler J, Schönfelder S, Bongers A, & Wessa M (2010). How to Regulate Emotion? Neural Networks for Reappraisal and Distraction. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991) PMID: 21041200