At BiM, we have often discussed the idea that learning processes might contribute to chronic pain (e.g., 1, 2, 3, 4). Researchers are also investigating whether other unpleasant states, such as fatigue, can be learned. For this reason we have invited researcher and psychologist Bert to tell us about his work.

It is normal to feel tired after a long day of work, an evening run, or in the presence of acute illness, where fatigue promotes resting and recovery. In some cases however, fatigue can become chronic and persist unnecessarily.

Fatigue persisting longer than six months affects one out of ten (or even more [1]) individuals, and is even more common in chronic disease states, including neurological and immunological disorders, cardiovascular disease, psychiatric illness, and fatigue related disorders such as chronic fatigue disorder and burn-out syndrome.

Despite the high prevalence of chronic fatigue, its development remains poorly understood and cannot be explained by biological variables alone. For instance, similar to other somatic sensations such as pain and dyspnea, fatigue complaints may exist in absence of (evidence for) physiological or neurobiological dysregulation [2]. Moreover, there is little, or at best inconsistent, evidence connecting fatigue symptoms to markers of chronic disease, indicating that other variables need be taken into account to explain chronic fatigue [3,4].

Against this background, I investigate whether fatigue may be influenced by our own experiences and what we learn from them. We recently developed the ‘ALT+F model’ – Associative Learning Trajectory towards Chronic Fatigue – that describes how learning may contribute to fatigue becoming a chronic symptom. Central to this model is that whenever humans experience fatigue, internal (e.g., bodily sensations) and external stimuli (e.g., work environment) become associated with fatigue through classical (Pavlovian) conditioning. Just as Pavlov’s dogs came to salivate at the sound of a bell because of association with food, stimuli associated with tiredness, may now evoke fatigue as a conditioned response. In burn-out syndrome for instance, the work environment has become a powerful trigger of fatigue (and distress) merely on the basis of previous experience. Indeed, we posit that individual learning histories may contribute to the development of fatigue symptoms triggered by various stimuli (such as the work environment), which may also explain why these stimuli are subsequently being avoided. Learning processes may thus loosen the, normally exclusive, link between fatigue and cognitive or physical effort or acute illness. In a recent theoretical review, we discuss the current clinical and experimental evidence for the ALT+F-model [5].

Not only might ongoing fatigue symptoms have a learning component, but they may be reinforced by the process of operant (behavioral) conditioning and the laws of reward and punishment. That is, if what we do about fatigue leads to temporary rewarding outcomes, fatigue might be reinforced. For example, resting might give temporary fatigue relief, and reporting fatigue to a loved one might attract care and attention. In that respect, fatigue complaints may be influenced by the reactions of our social environment. In a recent experiment, we demonstrated that fatigue can indeed be increased through social reinforcement [6].

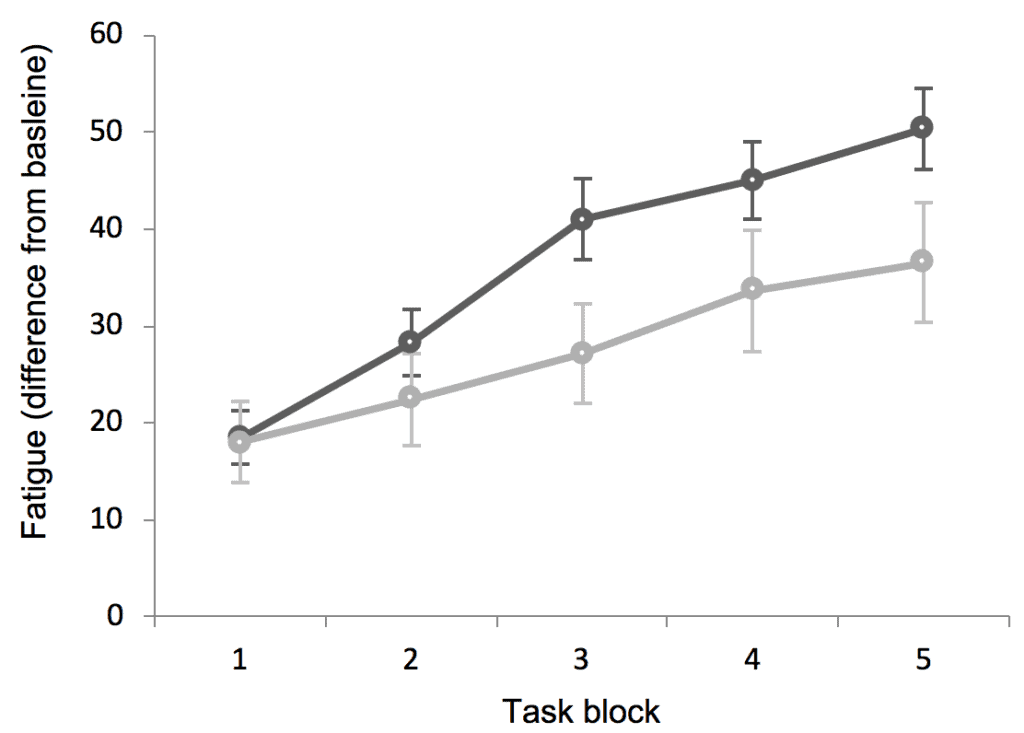

Forty-four healthy individuals were requested to repeatedly rate their fatigue while performing five consecutive blocks of a cognitively demanding working memory task. Crucially, for half of participants (the experimental group) subtle social reward was given by the experimenter (e.g., “That’s good”) whenever their fatigue ratings increased relative to their previous rating, and social disapproval (e.g., “Hmm, strange”) was given whenever their fatigue decreased. The other half of participants (the control group) only received neutral feedback to their ratings (“You may now continue with the next block”). The results depicted in Figure 1 show that fatigue increased in both groups, indicating that the task was indeed cognitively demanding. However, this increase was stronger in the group where fatigue increases were rewarded. What is more, this effect was unrelated to conscious awareness. That is, participants in this group were not aware that their fatigue ratings were being systematically reinforced.

Ultimately, gaining insight in how learning can contribute to chronic fatigue symptoms may open a new window on treatment. For instance, learned associations (e.g., between the work environment and fatigue) may be extinguished through exposure therapy, while rewarding behaviors consistent with higher levels of energy (operant conditioning) might be effective tools towards reducing fatigue.

About the author

Bert Lenaert, PhD, is a psychologist and postdoctoral scholar at the Limburg Brain Injury Center, Maastricht University in the Netherlands. In his current research, Bert uses the innovative method of experience sampling to better capture and measure fatigue in the flow of daily life of individuals who suffered brain injury. Further, Bert experimentally investigates how a common experience such as fatigue can become a chronic symptom, and specifically looks at the role of classical and operant conditioning therein.

Bert Lenaert, PhD, is a psychologist and postdoctoral scholar at the Limburg Brain Injury Center, Maastricht University in the Netherlands. In his current research, Bert uses the innovative method of experience sampling to better capture and measure fatigue in the flow of daily life of individuals who suffered brain injury. Further, Bert experimentally investigates how a common experience such as fatigue can become a chronic symptom, and specifically looks at the role of classical and operant conditioning therein.

References

[1] van ‘t Leven, M., Zielhuis, G. A., van der Meer, J. W., Verbeek, A. L., & Bleijenberg, G. (2009). Fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome-like complaints in the general population. European Journal of Public Health, 20, 251-257.

[2] Rief, W., & Broadbent, E. (2007). Explaining medically unexplained symptoms-models and mechanisms. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 821-841.

[3] Afari, N., & Buchwald, D. (2003). Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Answers sought. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 221–236.

[4] Kutlubaev, M.A., Duncan, F.H., & Mead, G.E. (2012). Biological correlates of post-stroke fatigue: A systematic review. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 125, 219-227.

[5] Lenaert, B., Boddez, Y., Vlaeyen, J. W., & van Heugten, C. M. (2018). Learning to feel tired: A learning trajectory towards chronic fatigue. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 100, 54–66.

[6] Lenaert, B., Jansen, R., & van Heugten, C. M. (2018). You make me tired: An experimental test of the role of interpersonal operant conditioning in fatigue. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 103, 12-17.