Why is listening to people so hard? A 4-Part Clinical Collaboration Reflection

Part 2

Collaborative care, in it’s current form, is not very scaleable. In chronic pain care, we have a situation where the people who need help most, have the least access to services (1). They have the highest barriers to change, the most complex social situations and the lowest means to change their circumstances. Their best care options have been opiates, emergency rooms and the lure of surgery to “fix” the structural problems. To adopt a collaborative model of care, we’re not starting with a clean slate, but with a battleground of blame and shame where everyone is hurting (2). Chronic pain is the most burdensome non-fatal disease on the planet, and the health care industry has contributed in some part to this dire circumstance.

I get to work in a health care wonderland – one that is reliant on the ability of people to pay for it, and those people can access many services to address the multiple facets of their pain. When people report meaningful changes in their lives and their pain, they invariably have had the means and the ability to have changed the context of their experience. They have the space psychologically and socially for the biological factors to change. In this optimal set up, I see people get their lives back. I also feel guilt that these optimal conditions are not available to most people, and I’m not touching the vastness of the challenge.

A critical part of collaboration is shared communication. In any team environment, to make a project work, you must be speaking the same language. Sharing stories using the same words enable us to work together effectively (3). To move toward bigger scale changes in how we help people in pain, we must work toward using the same words (4). Medical jargon has long been a division between patients and health professionals, and a way of maintaining and asserting power structures. Thanks to Doctor Google, and the unprecedented access people now have to information, we’ve broken that wall. Instead of being a threat to our power structures, we have the opportunity to bring another data source into the conversation. People come to us with their self-diagnoses, frequently catastrophic and alarming, that they’ve gleaned from the internet. Our professional skill set must evolve to effectively use online information and tools. For now at least, we’re better than Dr Google, and it’s our ability to listen to people and translate information with clinical findings that gives us that edge. While there is good information on the internet about pain, it’s unlikely to be found by the people who need it, and in a way that makes sense.

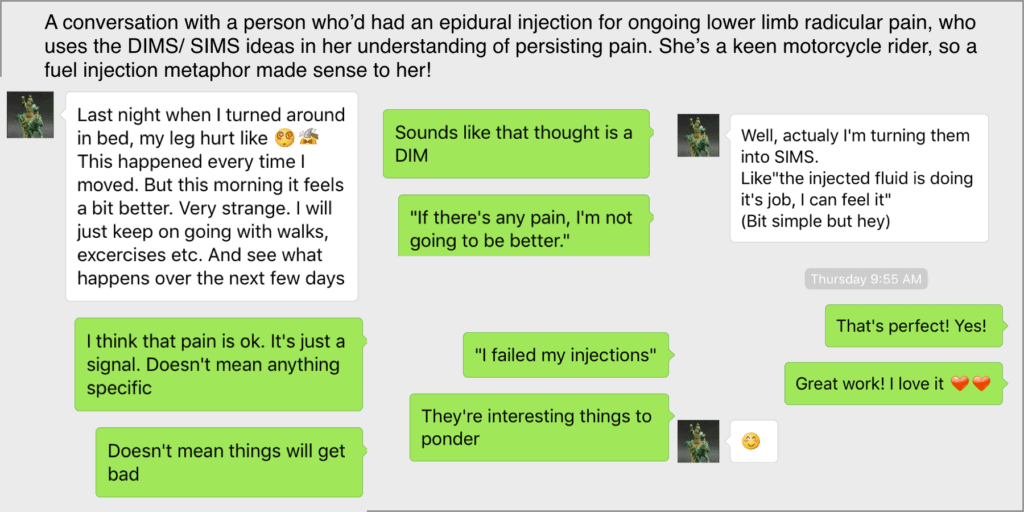

Helping people discover a new language and context is a precious gift. Using the words of danger and safety (5) in pain allows people to engage their creativity, and their whole life experiences (6). In the clinic, when we’re physically present to assess and observe, we act as the translator between a person’s story, and their physical sensations. For someone who cannot bend forward, and gets that sharp shooting pain that puts them on the floor, and is worried about the impending wheelchair-bound life, a gentle neurodynamic test or a movement cue is a way of building safety. It allows us to help them build a new story. Then we can show charts, models or tell stories of how nerves work, and how systems get sensitive more often than they get damaged. In the clinic, our job is to facilitate feeling sensitive but safe. A shared language about danger and safety allows a simple text message conversation to have a therapeutic value. Now we’re getting to something that might be scalable. Language is that powerful.

Coming up: Bring on The Pain Revolution

About Lissanthea Taylor

Lissanthea is an Australian Physiotherapist on the look out for the ways we can use technology, business models and social media to improve population health with regard to pain treatment. She’s working on getting better information to people in pain with her Pain Chats emails. She’s also part of the team that runs the Pain Revolution where she makes sure that the stories of the ride, and the ongoing community-based Local Pain Educator network reach the world.

Lissanthea is an Australian Physiotherapist on the look out for the ways we can use technology, business models and social media to improve population health with regard to pain treatment. She’s working on getting better information to people in pain with her Pain Chats emails. She’s also part of the team that runs the Pain Revolution where she makes sure that the stories of the ride, and the ongoing community-based Local Pain Educator network reach the world.

References

[3] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2939527/

[4] https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2474-10-123