This series of case studies about the creation and evolution of multidisciplinary pain clinics in developing countries is intended to provide examples of the ideas demonstrated in this manual.

CASE STUDY

MALAYSIA

Multidisciplinary Pain Clinic Founder: Mary Suma Cardosa, MBBS, anesthesiologist and pain specialist at Hospital Selayang; 2019 president of the Malaysian Association for the Study of Pain

Background

In Malaysia, the Ministry of Health (MOH) governs the country’s national health care system, including management of 153 public hospitals in its 13 states. Each state operates at least one large public hospital, with more-populated areas, such as the Klang Valley, having several. The country also has more than 200 private hospitals.

Both state and private hospitals, accept citizens and non-citizens, but state hospitals charge minimal fees for citizens and higher fees for non- citizens. The level of care in Malaysian hospitals is considered equal to that of many Western countries.

Health care professionals (doctors, nurses, physiotherapists and other allied health professionals) in public facilities are employed by the Ministry of Health (MOH), not by any individual hospital or clinic. This means that they can be assigned to any healthcare facility. When health care professionals are promoted throughout their career in the MOH, they may be re-assigned to new hospitals. This constant movement of personnel can create challenges to medical teams operating any type of clinic or department.

In addition, many health care professionals, especially specialist doctors, leave public hospitals to earn the higher salaries offered by private hospitals [1]. The higher ratio of physicians to patients in private hospitals also means patients may be assessed and treated sooner than at state hospitals, depending on the medical condition, which adds to the competitiveness of attracting patients. That said, private hospitals are concentrated in the cities, and patients who live outside of urban areas have less access to private health care.

The need for high-quality pain care is immense, especially as the country’s population ages. An estimated 1 million Malaysians “live with persistent pain, the vast majority (82%) of whom indicated that the pain interfered with their activities,” according to the Malaysian 3rd National Health and Morbidity survey [2].

For more information on the Malaysian pain landscape and health care system, see the Ministry of Health website at http://www.moh.gov.my/.

Launching a Multidisciplinary Pain Clinic (MDPC)

When Dr. Mary Cardosa finished her initial training in anesthesiology in 1993, Malaysia had one pain clinic, but it was not multidisciplinary. Not until 1997, when Dr. Cardosa became the first person sent overseas by the Malaysian government for specialized training in pain management, was a multidisciplinary approach to pain clearly understood and seriously considered.

During her year at Royal North Shore Hospital in Sydney, Australia, Dr. Cardosa learned about multidisciplinary pain management (MDPM) from Professor Michael Cousins and his team at the hospital’s Pain Management Research Institute, which included Michael Nicholas, PhD, a University of Sydney professor specializing in psychology and pain.

Inspired, upon her return in mid-1998, Dr. Cardosa was determined to set up a multidisciplinary pain clinic (MDPC), but was assigned to two other public hospitals before being reassigned in late 1999 to Hospital Selayang. This was a new facility which was developing new clinical services, so her department head and the hospital leadership were especially receptive when she shared her vision to start the country’s second pain clinic onsite.

By June 2000, she had organized and launched the Hospital Selayang Pain Clinic—the first in a Ministry of Health Hospital, and the first in Malaysia to use a multidisciplinary approach to pain assessment and treatment. The clinic operated twice a week and was outpatient only, focusing on patients with either cancer or non-cancer chronic pain. Earlier in her career, she started the Acute Pain Service in the same hospital, which focused on patients with acute, mainly post-operative, pain.

Dr. Cardosa and her new team (detailed below in Personnel) drew up a list of the types of patients they would see, including referral criteria and prioritization. Cancer pain patients, for instance, would be seen on the next available date, while patients with chronic non-cancer pain were scheduled later. The team circulated the list to all hospital departments and encouraged its doctors and specialists to send appropriate patients to the clinic. These referrals formed the initial pipeline of patients accepted by the new clinic. In addition, referrals were accepted from other hospitals (private and public) around the country, as well as from government and private primary care clinics.

Ideally, the entire team tried to meet on each clinic day afternoon after seeing patients in the morning and calling additional meetings if they needed input from other hospital departments such as rheumatology. In reality, though, uniting all members of the team every day was not always possible. Regular meetings were organized to discuss all new patients seen at the clinic.

PERSONNEL: Recruiting and Managing a Multidisciplinary Pain Clinic Team

Although Dr. Cardosa had submitted a formal proposal to the Ministry of Health outlining the staffing and resources needed to set up a multidisciplinary pain clinic, she initially had to rely on staff from existing departments in the hospital as approval from the MOH (for budget and staffing) could take many years to process.

Using her relationships with other hospital department heads and specialists, strong support of her own Anaesthesiology Department head and the hospital leadership as well as her own professional network and friendships, she successfully recruited a physiotherapist, a psychiatrist, and a nurse to staff the clinic with her twice a week. She did not need clerical assistance, because in Malaysian public hospitals, nurses handle administration such as making appointments, calling patients, and collecting data and surveys, in addition to their medical nursing responsibilities.

Also, because the clinic was located in the hospital, patients could use the hospital’s pharmacy and registration services for check-in, payments and medication, leaving the clinic free to focus primarily on patient care.

The physiotherapy department head at Hospital Selayang was proactive and supportive in 2000 during the clinic set-up, assigning a dedicated physiotherapist to the clinic. Dr. Cardosa felt fortunate to have such support, which continued through the years. Although all physiotherapists treat patients with pain, many do not differentiate between acute and chronic pain, leading to poor management of patients with chronic pain. Those physiotherapists assigned to the pain clinic developed the skills and knowledge to treat chronic pain patients, and although there were many changes of individual physiotherapists (due to transfers, promotions, etc.), the physiotherapy support has continued throughout the clinic’s existence, with a physiotherapist assessing and treating patients in the pain clinic, as well as participating in team meetings.

In addition to expertise in pain assessment and treatment, founders of MDPCs should be exceptionally skilled in relationship- building, creative problem-solving, and communicating with diverse audiences...

Dr. Cardosa also faced a shortage of clinical psychologists in Malaysia, which still continues to this day. In the early 2000s, the only career options for psychologists in the Ministry of Health were positions as “counselors,” a job title that was not as prestigious as other health care specialties and did not pay as well.

She continued searching for personnel from different specialties, especially a willing clinical psychologist. Through her friendship with the head of the Department of Psychological Medicine at the Universiti Putra Malaysia, she sought and obtained a stream of clinical psychologists and trainees.

In 2004, Dr Zubaidah Jamil Osman, DPsych, had just returned from her training in Melbourne and was assigned to the Hospital Selayang Pain clinic, four years after the clinic opening. The university gave Dr. Osman paid time off to help in the clinic, and after a few years, Dr. Cardosa obtained funding to pay her to serve as a part-time visiting consultant. Because Dr. Osman still lectured regularly and supervised students doing their master’s degrees in clinical psychology, she also brought her students to observe and help with assessments and basic treatments such as relaxation training. The arrangement worked for many years and has resulted in several clinical psychologists taking up an interest in pain management, including one who completed his Ph.D. in pain psychology.

In 2005, Dr. Cardosa expanded the multidisciplinary team again, recruiting a pharmacist and social worker. The pharmacist did not dispense medications from a dedicated clinic pharmacy since the main hospital had its own large pharmacy. He or she would come to the clinic to counsel any patient who may have been prescribed a new pain drug, such as methadone, or to assess someone who had an adverse drug reaction. While the first social worker at the clinic was enthusiastic and skilled, Dr. Cardosa had a difficult time replacing her with someone equally competent and dedicated after she was promoted and transferred to another hospital.

Challenges: Personnel

In addition to expertise in pain assessment and treatment, founders of MDPCs should be exceptionally skilled in relationship-building, creative problem-solving, and communicating with diverse audiences, according to Dr. Cardosa. The launch team also must be persistent, committed, and resourceful. Finding these combinations in the personalities and professional expertise of team members takes time and strong dedication.

Another challenge in the growth of the Hospital Selayang clinic was that, because clinic pain specialists were anesthesiologists, surgeons were frequently pressuring them to spend more time in surgery. In Dr. Cardosa’s case, since she was doing pioneering work in setting up the pain services, she began spending more time outside of the operating theater than inside. The strong support of her department and hospital leadership enabled her personally to continue focusing on pain clinic work, but she—like other Malaysian MDPCs--still had to wait for staff to be interested, available, and assigned.

In particular, Dr. Cardosa had no back-up physician. For the first three years, she served as the sole physician and pain specialist in the pain clinic. She had trainee pain physicians on and off, but they were assigned to different hospitals throughout the country before another pain specialist was assigned to Selayang Hospital. In addition, the anesthesia department, with an increase in the number of staff, managed to assign junior doctors (medical officers) to the pain clinic on a rotating basis. Thankfully, with the increase in number of trained pain specialists in the Ministry of Health, there are now at least two, sometimes three, pain specialists at the pain clinic in hospital Selayang, together with trainee pain specialists and medical officers.

Training and Troubleshooting

From the first day, Dr. Cardosa trained her clinic staff personally, using the afternoon meetings on clinic days to discuss patient cases, teach new skills, and learn as a team through shared experiences. The entire team “learned together,” since no member had much experience in a multidisciplinary pain environment.

Dr. Cardosa was the first anesthesiologist in the MOH trained in the subspecialty of pain medicine. After the establishment of a multidisciplinary pain clinic in Selayang Hospital, the MOH continued to identify and send interested anesthesiologists from other hospitals around the country for similar subspeciality training. A 3-year training program was developed, which included a year at Dr. Cardosa’s clinic and nine to 12 months of additional training overseas at pain centers in Australia, Singapore, Thailand, India and Korea.

The Malaysian government permitted specialist anesthesiologists doing subspecialty training to take up to a year away from their in-country work, providing their annual salary, as well as a monthly allowance for living expenses and training or conference fees.

New pain clinics in other government hospitals began building the same multidisciplinary model, first identifying (at the minimum) an available on-staff specialist anesthesiologist interested in training in pain medicine, together with a nurse and a physiotherapist and/or occupational therapist to set up the clinic. The specialist, who would eventually be the pain clinic director, would run his or her clinic while completing the three-year training program. During this time, Dr. Cardosa provided support by travelling regularly to the newly set up clinics and would provide the specialist input required to continue the service even while the trainee pain specialists were doing their overseas training, to ensure the facilities’ sustainability. As these other clinics grew, additional staff such as occupational therapists, pharmacists, psychiatrists, and clinical psychologists would be added to the team according to interest and availability.

Challenges: Training

One of the biggest barriers for the clinic at Selayang Hospital was that all staff working in the pain clinic also had other duties, serving not only patients with chronic pain but also other patients in the hospital — both inpatient and outpatient — from diverse disciplines such as general medicine, general surgery, urology, orthopedics, gynecology, pediatrics, intensive care, etc., This made the workload heavy and diverse, with many services completing for the staff’s time. Therefore, ongoing training in pain management was all the more important. This was true in the other MDPCs across the country, too—not all of which had the same level of support for their clinics or offered the same hospital services.

New MDPC founders, therefore, must become comfortable managing part-time personnel, recruiting and training new specialists specifically for pain patients, filling service gaps when staff leave, and accepting that (e.g. for physiotherapy) management of patients outside of the pain clinic may not be ideal but could be necessary.

The continued turnover of staff was another challenge. However, in most cases, Dr. Cardosa found that a departing individual had already identified and trained a successor to fill the vacancy, leading, at times, to availability of “extra” staff such as a second physiotherapist. This pipeline of trained, committed professionals has been essential to ensuring long-term sustainability of the facility.

Even with assigned staff, none worked solely for the clinic, so coordinating consistent workers could be difficult when other hospital or department duties infringed on clinic hours. Another issue was that even supportive hospital department leaders might assign different personnel to work at the clinic during different times, which could affect the consistency and culture of the team.

Dr. Cardosa was most successful at recruitment and retention when she was able to find people interested and committed to pain management and training; one way to capture interest was to show them first-hand how much patients could improve with the multidisciplinary approach.

The challenge was—18 months into the clinic’s evolution—she was still having problems fully discharging patients. Patients would visit the clinic and keep returning. Although specialist clinics in the MOH hospitals referred patients with hypertension and diabetes to their general practitioners or community clinics for long-term follow- up, patient with chronic pain had nowhere to go as there was little experience with the management of chronic pain in community clinics. How were MDPCs elsewhere resolving this problem?

Dr. Cardosa realized that she had to start a multidisciplinary cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) pain program in her hospital to complement the treatment of individuals attending the pain clinic. She applied for and was fortunate to secure funding from the Malaysian government for a four-person team from Hospital Selayang to observe the ADAPT program at the Royal North Shore Hospital in Sydney, Australia, for three weeks in December 2001. This program uses a pain self-management approach, incorporating goal-setting, activity-pacing, and practical problem-solving to instill new behaviors and thinking that can result in dramatic positive changes in patients with chronic pain.

The team included Dr. Cardosa, a nurse, a physiotherapist, and a psychiatrist. All were so impressed with their observations of the ADAPT program that they immediately began planning their own two-week version of the program and set a goal of launching it within six months. In June 2002, the group ran its first CBT program, calling it MENANG. The word means “win” in the native Bahasa Malaysia language, and the team developed the name from “Program MENANGani Kesakitan,” which translates to “Pain Management Program.” Dr. Michael Nicholas and Lois Tonkin, a physiotherapist from the Pain Management Research Institute (PMRI), came for a week each to help run the first MENANG program.

Costs had to be creatively covered. The clinic could not afford to pay for salaries of the visiting specialists, although it covered airfare and food, and the hospital provided lodging in the hospital doctors’ quarters, ensured adequate space, and enabled team members to participate. Dr. Nicholas was interested to see how and whether the CBT program—the first of its kind in Malaysia, and in Asia, could work in another cultural context, so he volunteered his time for the first MENANG program. Dr. Nicholas and PMRI continued to provide support by sending a clinical psychologist to help the Malaysian team to run the next three MENANG programs, and a clinical psychologist from the UK, Dr. Amanda C de C Williams, volunteered to come for the fifth MENANG program. After that, the local team was trained and confident enough to conduct the program by themselves, led by Dr. Cardosa and Dr. Zubaidah Jamil Osman. Dr. Cardosa credits the support and mentoring from Dr. Nicholas and Dr. Williams as core to the MENANG program’s success.

The results of 70 patients from the first 11 groups showed that patients made significant improvements in pain levels, disability and psychological well-being, which were maintained at one year.

Program outcomes proved dramatic for many patients. Patients attending the program came from all over the country and were assessed by the multidisciplinary team before being selected for the program. On the first day, the staff videotaped the patients walking a distance of 40 meters to study their gait, facial expressions, speed, and more. They were then given intensive multidisciplinary training in pain self-management with patient-driven specific goals (e.g., sitting for an hour, driving a car, etc.) to reduce their suffering. The program included moving the patient away from any prescribed pain medications, increasing exercise and movement, and adopting other non-pharmacological techniques.

After two weeks, patients were again filmed. The results were near- universal improvement, sometimes almost “like magic,” to quote one of the patients. Best of all, the improvements were generally sustained. Patients returned for follow-up after one month, three months, six months, and one year before being discharged from the clinic.

One patient who sustained a severe arm injury with nerve damage (brachial plexus palsy) in a motorcycle accident progressed so much that he started returning to speak to other skeptical patients about his much- improved quality of life. This two-hour patient-to-patient storytelling is now part of the program, and new patients feel supported and understood, so they better trust and engage with the program.

The pain clinic staff, meanwhile, began using the before-and-after patient videotapes to train other medical staff and reference in medical lectures. The results of 70 patients from the first 11 groups showed that patients made significant improvements in pain levels, disability and psychological well-being, which were maintained at one year; as described in a 2011 article in Translational Behavioral Medicine [3].

FACILITIES: The Multidisciplinary Pain Clinic Environment

Hospital Selayang did not have the option of separate facilities for a MDPC. Dr. Cardosa started the pain clinic using two multi-use rooms shared with other specialists, because the clinic was not running every day. Some space was dedicated for anesthesia, so clinic operations were run there initially, and physiotherapy treatments sometimes required patients to go to the hospital gym.

Dr. Cardosa considered herself lucky to have identified space, since obtaining government funding to set up an entirely new facility is very difficult and takes extensive lobbying and political outreach. Other departments also pressured them to leave since other services in this relatively new hospital were also expanding.

Although she did not receive direct permanent funding for a physical facility, she did find her facility challenges resolved in more recent years by a retiring hospital hand and microsurgery surgeon who led another department and appreciated that the clinic had effectively treated his referred patients. To ensure his large space was used well after his departure, he offered her five consulting rooms and a procedure room for her clinic.

For the MENANG program, the clinic also used a room next to the palliative care ward, because Dr. Cardosa had helped establish that ward and was part of the team that obtained funding to set up this room. Other MDPC directors in Malaysia also became adept at actively searching for existing space and presenting compelling cases that a clinic was good use of those areas. In 2019, many MDPC facilities still are not able to include physiotherapy and its needed equipment as part of the clinic space, so patients must go to a gym elsewhere in the hospital.

Because the Hospital Selayang Pain Clinic is public, patients pay any fees at the counter along with any other hospital patients. In addition, the pain clinic does not have a dedicated pharmacy but instead relies on the main hospital pharmacy to dispense medications.

An outstanding goal is still to unite all clinic care in one area, as is done at the Royal North Shore Hospital, Australia.

The Multidisciplinary Funding Model

Multidisciplinary pain clinics in Malaysia are funded indirectly by the Malaysian government as part of its investment in public hospitals, and start-up funds and expansion usually require repeated applications and often two to five years of process time. The government is very supportive of and interested in ways to ensure that Malaysian citizens can access high-quality health care.

Advance planning and strong relationships with hospital leadership help clinic directors ensure any funding requests are well-considered.

MEASURING OUTCOMES: Defining And Meeting Clinic Goals

Because Dr. Cardosa had worked in Hospital Selayang and elsewhere for many years, she understood the pain needs of its patients and had built strong relationships with fellow staff. She also felt strong pressure from hospital leaders to launch an MDPC soon after she returned from her Australian training. Indeed, they noted they would not send another physician for similar training until they witnessed what she achieved in Malaysia first. Thus, Dr. Cardosa’s first clinic opened without any prior data collection beyond what the hospital routinely gathered on its own.

Measuring outcomes became more essential once the clinic opened, and Dr. Cardosa needed to show the return on investment for her training. Below are some key outcomes from the years since the clinic launched:

Outcome 1: At least one multidisciplinary pain clinic exists in every state in Malaysia.

Up until her retirement in 2016, Dr. Cardosa trained most of the pain specialists working in the public hospitals in Malaysia. These specialists have gone on to set up, sometimes with the assistance of Dr. Cardosa personally, pain clinics in other parts of the country. To date, at least one multidisciplinary pain clinic exists in every state in Malaysia. Data from the annual census of pain clinics in MOH hospitals show that, in total, there are 14,000 patient visits at the outpatient pain clinics annually. This is in addition to the inpatient cancer pain and acute pain services run by the pain specialists.

Having retired from full time public service in 2016, Dr. Cardosa continues to serve as a visiting consultant to the MDPC at Hospital Selayang, which continues to run twice a week. The movement toward creation of more MDPCs has helped hospitals optimize facility space and existing resources, build their reputations as public health care leaders, and address specific pain needs of an aging patient population.

Outcome 2: Patient numbers are up.

In its first six months, the MDPC at Hospital Selayang served approximately 30 patients with chronic pain. Nearly 80 patients with different conditions were served in year two, and by 2019, that number had ballooned to 200 to 300 new patients making 1,500 to 2,000 patient visits annually, including follow-up appointments.

Demographic data show that patients also are traveling from around the country to visit the clinic, although this has diminished with the establishment of MDPCs in different states throughout the country.

Outcome 3: MDPC services to patients and external medical personnel have expanded.

Services offered at the MDPC still include assessment and treatment of patients with post-operative pain and cancer/non-cancer pain, but the clinic has now reached advanced operation and emphasizes more pain self-management, as well as more follow-up of patients discharged with strong opioids after surgery or multi-trauma. The latter may be asked to come to the clinic once or twice to ensure that they do not continue with strong opioids once the acute pain has settled; if the pain becomes persistent (chronic), then staff emphasize self-management and non-pharmacological management, while at the same time weaning them off the strong opioids.

The facility’s evolution into a model MDPC also has transformed it into a major training center for health workers of all disciplines to learn more about pain. Observers have been part of the clinic’s daily operations since day one, especially for the MENANG program. In fact, observers often outnumber patients during the two-week MENANG program.

Dr. Cardosa uses these events and ongoing operations to train staff from other pain clinics, including occupational therapists, pharmacists, physiotherapists, social workers, nurses, and physicians. Observers must participate in teaching discussions and team meetings, where

patient and treatment challenges are explored. After they witness firsthand the patient impact due to a multidisciplinary approach, revision of patient goals, and training in self-management, they must submit a final report of their new knowledge.

Outcome 4: If ranked informally on a maturity scale of Levels 1 (foundational) to 3 (advanced), the Hospital Selayang Pain Clinic would be Level 3 (advanced).

The expanded services, strength of the MENANG program, and extensive professional training program are among the reasons why Dr. Cardosa would describe the Selayang Hospital clinic as “Level 3—Advanced.” (See clinic maturity chart on page X.) The number estimates level of maturity and scope of impact a multidisciplinary pain clinic have in its operations and patient outcomes.

Outcome 5: Multidisciplinary pain management training has grown.

After seeing the resulting outcomes from Dr. Cardosa’s Australian training, the Malaysian government sent a second anesthesiologist for a yearlong pain management training in 2002. He later set up his

own multidisciplinary clinic on the east coast of peninsula Malaysia. Following that training, others have been trained in Australia, Singapore, Thailand, Korea and Canada, returning to the country to further transform pain treatment throughout the states.

In addition, teams from other hospitals who observed the MENANG program began to replicate the training and multidisciplinary approach in other clinics and hospitals across the country, although in shorter, less-intensive versions of the program.

Outcome 6: Much of the growth in patient clientele is due to the excellent reputation and greater awareness of the MDPC clinic.

As noted earlier, core to recruiting good clinic staff and volunteers has been the ability to demonstrate genuine patient improvement, the importance of the work, and the ways that they, too, can make a difference.

The clinic uses several creative approaches to reinforce these positive outcomes.

- First, the videotapes of improved patients in the MENANG program are shared with professionals at trainings and conferences, so interest has built. Seeing progress so quickly and providing self- reported patient data that show suffering has diminished has been compelling to professionals and trainees of myriad specialties.

- Second, patient graduates of the clinic’s MENANG program return to speak to new patients, making the latter feel supported, understood, and optimistic. In one patient case at Hospital Selayang Pain Clinic, a MENANG patient graduate who lost use of his right arm in a motorcycle accident has returned annually for more than a decade--determined to help other frustrated patients regain hope, develop more control over their pain, and reduce unhelpful thoughts that cause much of their suffering.

Outcome 7: Data collection is embedded into daily clinic operations, and its results encourage others to start MDPCs and CBT programs.

All patients who visit the clinic receive questionnaires that determine a baseline of their health. If they go through MENANG, their progress is tracked for the first year.

Dr. Cardosa and her colleagues published a 2011 paper in Translational Behavioral Medicine, which showed results in the first eleven groups (70 patients) that equaled patient improvement statistics found in populations of Western countries. The clinic has continues to gather important data during its two MENANG programs a year, in addition to twice-weekly outpatient and daily inpatient services.

Challenges: Outcomes

Challenge 1: Benchmarking and data analysis are too resource- intensive to maintain.

Although the clinic tracks patient data, including demographics, diagnoses, and more, it has a harder time finding resources to fully analyze and benchmark the information. The Selayang Hospital Pain Clinic does not have a strong system for retention and analysis of data, in part because it is focused on tracking and analyzing data of MENANG graduates.

In contrast, the CBT program at the MDPC in Australia with Dr.

Nicholas collects and compares data from its patients to all patients countrywide. This enables his clinic to know the quality of its work and encourages staff and volunteers to improve and learn. It is this model that Dr. Cardosa hopes all MDPCs in Malaysia will achieve in the future.

Challenge 2: Maintaining quality of care in every state requires more public pain specialists and pain psychologists.

Once medical staff leave, they may not be assigned to run pain clinic services. The movement developed by Dr. Cardosa has led to creation of MDPCs in every state “in principle,” but some have “lost” their pain specialists, as there is constant movement of specialists from public hospitals to the private sector. The low number of pain specialists in the country means that any departures from state to private practice could be highly impactful to patient care and clinic sustainability. Although those clinics still run, their directors are often junior physicians who may have inadequate training in pain management and assessment.

References

[1] Yang SS. Public versus private on medical care. Borneo Post Online. Published online 12 December 2020. Accessed 9 September 2019. http://www.theborneopost. com/2010/12/12/public-versus-private-on-medical-care.

[2] Cardosa MS, Gurpreet R, Tee HGT. Chronic Pain, The Third National Health and Morbidity Survey 2006, vol. 1. Kuala Lumpur: Institute for Public Health, Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2008:262.

[3] Cardosa M, Jamil Osman Z, Nicholas M, Tonkin L, Williams ACC, Aziz KA, Ali RM, Dahari NM. Self-management of chronic pain in Malaysian patients: effectiveness trial with 1-year follow-up Transl Behav Med. 2012; 2(1): 30–37. Published online 2011 Dec 6. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0095-2.

CASE STUDY

PHILIPPINES

Multidisciplinary Pain Clinic Founder: Jocelyn Que, MD, MMed, FPBA, anesthesiologist at the Center for Pain Medicine, University of Santo Thomas, Manila, Philippines

Background

Health care in the Philippines is provided through a dual health delivery system composed of the public sector and the private sector [1]. The public sector is largely financed through a tax-based budgeting system to government health care facilities; while the private sector is largely market-oriented, with fee-for-service options. Nearly 60% of hospitals in the country are privately run, and they serve approximately 30% of the Filipino population. The remaining 40% of hospitals are public [2].

According to the 2018 Global Data on Cancer, more than 140,000 new cancer cases and more than 80,000 cancer deaths are expected in the Philippines each year [4].

Social health insurance under the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth) was introduced in 1995 to provide financial risk protection for the Filipino people. PhilHealth reimburses government and private health facilities, and reportedly covers 92% of the population in 2017 [3]. However, financial protection is limited such that pain management and palliative care services are not covered, resulting in a high level of household out-of-pocket payment.

The burden of untreated pain and its impact on the quality of life of the patients and their families are most evident in patients with cancer.

According to the 2018 Global Data on Cancer, more than 140,000 new cancer cases and more than 80,000 cancer deaths are expected in the Philippines each year [4]. To provide cancer patients better access to more responsive and affordable healthcare services, Republic Act No. 11215 otherwise known as the National Integrated Cancer Control Act (NICCA) was signed into law in 2019. The new law also aims to expand PhilHealth packages for Filipinos diagnosed with cancer and mandates the establishment of the Philippine Cancer Center to ensure access to cancer care services and medicines. By institutionalizing interdisciplinary/multidisciplinary care with a whole-of-government, equity-based, and life-course approach, access to quality and affordable care for cancer patients and survivors will be attained.

Launching a Multidisciplinary Pain Clinic (MDPC)

In the Philippines, the first pain clinic was established in 1987 by the Department of Anesthesiology, Philippine General Hospital, a tertiary state-owned hospital and operated by the University of the Philippines, under the vision and guidance of Dr. Cenon Cruz. Fresh from his training in Pain Medicine at the Seattle Multidisciplinary Pain Center under the tutelage of Prof. John J. Bonica, the clinic opened with a team of 3 anesthesiologists (including Dr. Cruz) and was later joined by an acupuncturist.

It was in the same year 1987 that the Pain Society of the Philippines was founded during the IASP World Congress in Hamburg, Germany where the Philippine delegation was led by Dr. Cenon Cruz. The first assembly of highly motivated physicians (anesthesiologists, neurologists, neurosurgeons, oncologists, rehabilitation medicine specialist, acupuncturists and residents in training) was convened by the group who attended the World Congress. This was geared towards unifying different specialists under one single organization. Prior to this, the concept of multidisciplinary approach to pain management was unheard of and each specialist operated his own pain clinic.

In 1988, the University of Santo Tomas Hospital (USTH) established a part-time pain clinic offering pain consultation but few other services. The facility was led by Dr. Dominador Braganza who had some training in interventional pain practice in Germany. The pain team comprised of a few healthcare professionals who had taken short courses in pain but had little experience or advanced pain training. Although it may have been viewed as multidisciplinary at the time, the approach was not as strictly defined as today.

In 1993, Dr. Cenon Cruz established the first fully multidisciplinary pain clinic (MDPC) in the country at St. Luke’s Medical Center-Quezon City (SLMC-QC), a well-funded private medical center. Health care professionals from various specialties and disciplines were assembled to work together in addressing the biopsychosocial dimensions of pain. As was the case in other pain clinics, most of the patients seen had cancer-related pain, but later evolved to include non-cancer pain conditions. Subsequently, other multidisciplinary pain clinics were organized and a few pain clinics were restructured into MDPCs. One of these was the USTH Pain Management and Palliative Care Unit.

Cognizant of the huge knowledge and skills gap in pain management in the country, Dr. Jocelyn Que pursued advanced studies at the University of Sydney and clinical fellowship training in Pain Medicine at the Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney, Australia, under the mentorship of pain pioneer and University of Sydney Professor Michael Cousins, and his staff in 2005. The training inspired her to want to develop similar MDPCs in the Philippines. It was fortuitous when, upon her return in 2006, the director of the newly established Benavides Cancer Institute at UST Hospital appointed Dr. Que as Head of the Pain Management and Palliative Care Unit to improve services for cancer patients and supported the vision of adopting a multidisciplinary approach to pain management in the re-envisioned pain clinic.

This support from the administration was key to the immediate establishment of the multidisciplinary Pain Management and Palliative Care Unit. The clinic continued to serve 100 patients in its first year, but that number—and the attention of other local healthcare leaders-- began growing steadily.

Because fully trained Filipino pain specialists were not common then and now, they often affiliate with multiple clinics. Thus, Dr. Que has collaborated with other pain specialists and health care professionals in establishing MDPCs in other hospitals and remains affiliated with these pain clinics.

PERSONNEL: Recruiting and Managing a Multidisciplinary Pain Clinic Team

The USTH Pain Clinic was already a functioning pain clinic under the Department of Anesthesiology when Dr. Que returned in 2006 from her pain fellowship training. The pain clinic then was merely a cubicle containing a desk, two chairs, and a bed/examination table in the Anesthesia department office. Though the USTH is a private tertiary university hospital with a capacity of 352 private and 250 service beds, only an average of 100 patients per year were referred to the pain service before 2006.

With the mandate from the Director of the USTH Benavides Cancer Institute to restructure the pain clinic to better serve the multidimensional needs of the cancer patients, Dr. Que transitioned it to multi-modal operations with an interdisciplinary team and merged it with the palliative care service to create the current pain management and palliative care unit (PMPCU).

When Dr. Que began the transition, the USTH MDPC started with one nurse and four pain physicians. In response to the lack of trained health care professionals in the pain team, Dr. Que actively sought and eventually found Australian fellowship training positions with stipends that enabled three of her identified colleagues—a clinical psychologist, a pediatric pain specialist, and a palliative care physician—to train in multidisciplinary pain management in Australian hospitals. Funding for the clinical psychologist training was provided by an IASP SCAN Design Foundation fellowship grant.

Staffing of Filipino MDPCs grew considerably during the past 13 years.

In 2019, UST Hospital clinic has six pain physicians (two of whom are full-time), three palliative care practitioners, and one full-time pain nurse. In addition, clinic staff can refer patients to a clinical psychologist/ psychiatrist from the Department of Neurology & Psychiatry or to a physical therapist or occupational therapist from the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Science. Patients may be seen by these health care practitioners in the MDPC or in their respective clinics where the needed equipment and space for treatment are housed. As her staff developed, Dr. Que introduced more services, upgraded pain assessments, introduced psychosocial assessments, and offered various pharmacologic and non- pharmacologic approaches, including cognitive behavioral therapy, acupuncture and interventional pain procedures.

In the upscale private hospitals like St. Luke’s Hospital-Global City, its MDPC staff in 2019 includes eight pain specialists, two palliative care physicians, eight pain nurses, two palliative care nurses, two palliative care physicians, an adult psychologist, a pediatric psychologist, a social worker, a chaplain, and an addiction medicine specialist/physician who also is a psychiatrist. A clinical pharmacist works for the clinic part-time, meeting with its patients to advise them on drug side effects and the best ways to take and store restricted drugs such as opioids.

A fellowship training program in pain medicine also has helped grow the pain staff and continued the growth of clinic services such as more interventional procedures and increased numbers of family conferences and multidisciplinary team meetings.

Dr. Que recommends that new MDPCs begin with a minimum staff of three pain specialists, although five would be ideal. If a clinic aims to provide seven-day coverage, she notes that it would likely operate most efficiently with seven pain nurses, three palliative care nurses, and a clinical psychologist trained to help patients in pain.

The staff size would depend on the institution, location, and needed services; highly urban areas may need a bigger staff, since many pain specialists rotate to different hospitals on different days. If the institution can support full-time hospital pain doctors in the clinic, the staff size could be smaller. Dr. Que, for instance, served as the UST Hospital clinic’s second palliative care physician and rotated among facilities regularly.

As a private hospital, St. Luke’s Medical Center had a different staffing scenario. Operating 24 hours a day seven days a week, the MDPC had two of its 10 nurses on duty for every eight-hour shift. Nurses were able to assess and monitor in-patient and out-patient patients around the clock. If a cancer patient was too ill to come into the clinic, a healthcare professional such as a physician or palliative nurse visited them at home.

Challenges: Personnel

A common personnel challenge for most MDPCs in the Philippines has been the unavailability of a clinical psychologist who is trained in the psychosocial assessment and psychosocial approaches to pain management, which is essential for a truly comprehensive patient and pain assessments and management. To address the issue, in 2010, Dr. Que invited Prof. Michael Nicholas of Royal North Shore Hospital and his team of a pain nurse, psychologist, and physical therapist to visit Manila Doctors Hospital and lead a two-week multidisciplinary workshop on teaching patient self-management skills. Also, a clinical psychologist of the USTH MDPC was sent to the Royal North Shore Hospital to train under the tutelage of Prof. Nicholas through the IASP SCAN Design Foundation fellowship grant. However, after working at the MDPC for three years, the clinical psychologist left the country to start a family with her Australian husband.

Indeed, the swift turnover of trained health care staff has been a common problem in the country. With the Philippines being a major exporter of health care professionals, it constantly grapples with the shortage of health providers, sometimes inevitably leading to poor quality of health care and high stress levels among health care staff. Furthermore, the country suffers from a disparity in the distribution of health workers in the country, where health workers prefer to work in urban than rural areas.

Another major challenge of the USTH MDPC was the lack of funding for a full-time pain nurse, which meant that the pain physicians had Essential Pain Management Lite University of Santo Tomas March 2015 Essential Pain Management Participants Davao Regional Hospital May 2015 to provide her salary. As a private hospital, USTH does not provide salaries for the physicians, only for employed hospital staff like nurses, pharmacists, physical therapists. With only one pain nurse, the USTH MDPC operated only in the day and pain referrals at night were addressed by the pain practitioners themselves.

Training and Troubleshooting

Education and training of MDPC personnel is an ongoing necessity. Clinic staff must continue to learn foundational pain management, as well as keep up with emerging pain research and treatments.

Because there was no formal education on pain management in the undergraduate medical and other health sciences curricula, Dr. Que has used the Essential Pain Management (EPM) program as an introductory module for all members of the USTH MDPC. This program was developed by Dr. Roger Goucke, a pain medicine physician in Perth, Australia, and Dr. Wayne Morris, an anesthesiologist at the University of Otago in Christchurch Hospital, New Zealand. The module provided a simple framework of how to approach a patient with pain.

In 2014, Dr. Que invited Dr. Goucke and Dr. Mary Cardosa, founder of the first multidisciplinary pain clinic in Malaysia, to the University of Santo Tomas to hold an inaugural EPM workshop. The three-day workshop attracted 50 health care professionals and sought to increase pain awareness countrywide. The workshop included a first day of EPM basics, while day two became a separate half-day instructor course that covered how participants could better teach the module. Day three required participants to run the course themselves and lead small- group discussions. Key leaders of the Pain Society of the Philippines attended this workshop at the invitation of Dr. Que. Impressed, the society decided to offer the workshops nationwide, an initiative that was launched in 2015 and is ongoing.

To address the knowledge gaps on pain in the undergraduate medical curriculum in the University of Santo Tomas (UST), Dr. Que and the pain education team under the Center for Pain Medicine, UST Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, has incorporated the EPM module into the curriculum of fourth year UST medical students. The team also traveled out of town to teach the EPM program to health care professionals in other institutions.

In 2008, the UST Faculty of Medicine and Surgery collaborated with the University of Sydney to offer purely online postgraduate studies in pain management to health care professionals who are interested in advancing their knowledge and understanding of pain and its Pain Self-Management Trainers’ Course manila 2018 Multidisciplinary Participants in Pain Self-Management Trainers’ Workshop at University of Santo Tomas in Manila in 2018 management. This program enabled health care professionals from South East Asia, India and Pakistan to learn at a reduced cost. To date, 60 health providers have enrolled in the program, of which 21 have graduated with the degree of Master of Medicine in Pain Management (for medical practitioners) and 3 with the degree of Master of Science in Pain Management (for non-medical health care professionals).

Challenges: Training

One of the most common problems for MDPCs has been funding shortages. Additional funding would have enabled the clinics to “easily hire staff, conduct research, and provide training,” says Dr. Que.

Financial support varies by institution. In the Philippines, to qualify as a pain specialist, a physician must complete two years of training in an accredited post-doctoral fellowship training program. To date, there are only 4 institutions with accredited pain fellowship training programs (with stipends provided to fellow trainees), namely: St. Luke’s Medical Center-Quezon City, St. Luke’s Medical Center-Global City, University of the Philippines - Philippine General Hospital, and Manila Doctors’ Hospital. No fellowship training program has been offered at UST Hospital due to funding concerns.

Another challenge is training members of the MDPC on the biopsychosocial dimensions of pain and the multidisciplinary approach to pain management. With the lack of clinical psychologists familiar with psychological approaches to pain management being a continuing problem in the country, a program that would teach patients how to self-manage their pain would help address this problem. It was in 2018 that such a workshop was conducted by Prof. Michael Nicholas and physical therapist Maria De Sousa from Royal North Share Hospital as a four-day skills training program. The workshop taught health care professionals what and how to teach patients pain self-management skills. Acquiring self-management skills will enable patients to function and cope with their pain by themselves and will help streamline referrals that would require involvement of a clinical psychologist.

Despite a major typhoon in Manila that required the workshop to move from site to site, 28 attendees completed the MDPC training.

FACILITIES: Creating the Multidisciplinary Pain Clinic Environment

From the facilities standpoint, the USTH pain clinic before 2006 was made up of a cubicle containing a desk, 2 chairs, and a bed/ examination table in the Anesthesia department office. With its transition into a MDPC, the USTH PMPCU was moved to a different site — the USTH Benavides Cancer Institute building — where it has one consultation room dedicated for its sole use and shares a common reception area, outpatient consultation rooms, library and family conference room with the interdisciplinary team at the USTH Benavides Cancer Institute.

Due to limitations in space and budget, equipment such as patient- controlled analgesia pumps and ultrasound machines were shared among the different departments/units. Interventional pain procedures requiring use of fluoroscopy were done in the operating room or in the procedural room of the Interventional Cardiology unit.

In the Philippines, there are only three MDPCs that exist as independent units, unlike most of the other MDPCs which are under the Department of Anesthesiology. The MDPC at St. Luke’s Medical Center-Global City (SLMC-GC) is an independent unit and has dedicated unit space larger than that of USTH PMPCU, including two or three consultation rooms assigned solely for pain management and palliative care unit, and a family conference room for patient discussions or multidisciplinary team meetings. The physiotherapists and occupational therapists reside in their own well-equipped rehabilitation centers, and pharmacists are headquartered in each main hospital pharmacy for all three MDPCs. The SLMC-GC has a 528-bed capacity and offers a two- year pain medicine fellowship training program.

BUDGET: Funding Challenges for Long-Term Sustainability

As a private university/teaching hospital, the USTH sustains itself mainly on patient fees and, to a small extent, from PhilHealth subsidy as an accredited health care facility. However, the practice of Pain Medicine has not been recognized as a specialty in the Philippines so patients and pain practitioners could not claim PhilHealth benefits for pain services.

Both long- and short-term funding remain as major concerns. Despite its continuing growth and high reputation among patients, the clinic does not compete well in terms of revenue generation or its return on investment against other hospital services.

As part of the USTH PMPCU’s responsibility of educating the hospital staff and the public and to help sustain the salaries of the pain nurse and secretary, Dr. Que conducts regular educational activities though this contributes only in the short term. In the long term, the clinic needs greater hospital administration support. With the change of hospital administrators, the new MDPC director needs to build and maintain strong relationships and communication channels with the hospital administrators to help ensure adequate, sustainable funding for clinic services, operations, and personnel.

MEASURING OUTCOMES: Defining and Meeting Clinic Goals

Hospitals with MDPCs regularly audit each departments and section, so clinic staff recognize key performance indicators, regularly collect patient satisfaction surveys, and comply with quality measurements. In addition, internal and external audit teams of the hospitals visit the clinics quarterly to check records, staff, credentials, training, patient satisfaction, and sample patient records.

When Dr. Que began at the UST Hospital in 2006, no data for the clinic had been collected, so she was unable to conduct needs assessments and other research. Lack of funding has continued to prevent the clinic from collecting or analyzing as much data as it would like.

In 2013, USTH Benavides Cancer Institute surveyed cancer patients to identify their symptoms and how they correlated with other demographic data [3]. The survey revealed that cancer patients suffered from three top symptoms: pain, anxiety, and a poor sense of well-being. As an offshoot, Dr. Que and her colleagues conducted another study [5] and reported that one-third of patients with cancer had experienced or were experiencing depression. The findings further validated the need for psychological expertise and training of clinic staff and psychological services for clinic patients.

Here are some of the key outcomes of the 32 year-old pain clinic.

Outcome 1: Clinic patient numbers are up significantly.

The UST Hospital pain clinic served approximately 100 patients in the year before Dr. Que transitioned it to a multidisciplinary facility. That number has climbed to 500 annually in 2019. Most of these patients (70-84%) had cancer-related pain, 14-24% had chronic non-cancer pain and 2.3-6% presented with acute pain. Patients with acute postoperative pain were managed by the anesthesiologist, and only the patient who presented with complex pain conditions or non-responsive pain will be referred to the pain service. Only SLMC-GC mandates that all postoperative patients need to be evaluated by the MDPC pain specialist.

Outcome 2: The MDPCs are at various levels of expertise and sustainability.

Dr. Que considers St Luke’s Medical Center to be a Level 3 MDPC on a rating scale of Level 1 (foundational) to Level 3 (advanced) because of its healthy financial condition, large staff size, myriad comprehensive services, and high-quality equipment.

She rates UST Hospital at Level 2 (intermediate), citing infrastructure gaps, smaller multidisciplinary staffs, and lower funding for and assignment of pain and palliative nurses. UST Hospital is offering more educational opportunities and adding new construction that may benefit the clinic, though, so this informal ranking may deserve reevaluating in a year or two. Despite these limitations, patient outcomes show improvement in clinical parameters such as pain reduction, return to function or work, enhanced quality of life, and patient satisfaction.

Outcome 3: The MDPCs have been helpful training centers for undergraduate and graduate pain trainees and pain education across the country and South East Asia.

Dr. Que continues to teach Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine to undergraduate medical students at UST and at the clinic. Her training in Sydney and clinical work at UST Hospital also inspired her and a multidisciplinary team of colleagues to collaborate with the Pain Management Research Institute, University of Sydney and establish the online master’s degree program in pain management for post-graduate physicians in Southeast Asia, India, and Pakistan in 2008.

The Developing Countries Project: Initiative for Improving Pain Education grant by the International Association for the Study of Pain was instrumental in jumpstarting the organization of the online graduate studies program. The grant supported a three-day training workshop on online facilitation for the multidisciplinary and international faculty of the online master’s degree program in 2008.

This program was later expanded in 2015 to offer the master of science degree in pain management to non-medical health care professionals in the same regions.

Outcome 4: Support by hospital leadership proved critical but did not alleviate all challenges in the first year of the MDPC.

Ensuring sustainable clinic support required educating and negotiating with administrators about the unique needs of MDPCs. However, the hospital was not as forthcoming with administrative support and unit space, nor did it accommodate requests to address the clinic’s primary challenge in year one: funding a pain nurse who could manage administrative as well as clinical or patient care duties. With the recent change of hospital administrators on October 2020, it is hoped that our voice will be heard and a few of our requests will eventually be granted.

Challenges: Outcomes

Although the number of MDPCs in the country is slowly growing, these facilities will continue to face difficulties. The UST Hospital Pain Management and Palliative Care Unit has been short of personnel and funding since its inception as a MDPC in 2006, yet this has not deterred its inception, operation and growth and continues to serve patients with pain problems. There is still much that can be done and needs to be done. The MDPC Director shall persevere in communicating with the hospital administration to make them better understand the nature of the practice of Pain Medicine and the essential components to ensure the delivery of quality pain management for our patients. Members of the multidisciplinary pain team should share a common vision and communicate regularly to achieve the patients’ goals and the clinic’s raison d’etre.

The Philippines is moving steadily toward a more multidisciplinary pain management approach. The recent approval of the National Integrated Cancer Control Act is providing a much-needed impetus for the creation of pain management and palliative care services and an increased availability and accessibility of pain medications for Filipino patients. The shift increases the urgency for education and training of more health care professionals on the multidisciplinary approach to pain.

Dr. Que is optimistic that the country is advancing in the right direction and would do so faster with greater financial and educational investments, as well as with the combined energy and efforts of diverse but collaborating stakeholders.

References

[1] The Philippines Health System Review. Vol. 8, No. 2. Dayrit MM, Lagrada LP, Picazo OF, Pons MC, Villaverde MC. New Delhi: World Health Organization, Regional Office for South East Asia, 2018.

[2] TransferWise. Healthcare in the Philippines: A Guide to the Filipino Healthcare System. Published 28 September 2017. Accessed 9 November 2020. https://transferwise.com/gb/blog/healthcare-system-in-the-philippines

[3] Bacorro WR, Que J, Sy Ortin TT, Feeley TW, Reyes-Gibby CC. A Cross-sectional Analysis of Symptom Burden among Adult Cancer Patients in a Filipino Tertiary Care Cancer Center. J Clinical Oncology 33, no. 29_suppl (October 10, 2015) 98-98. DOI: 10.1200/jco.2015.33.29_suppl.98

[4] Unite B. Better health care for cancer patients ensured as cancer law’s IRR signed. Manila Bulletin. Published 12 August 2019. Accessed 9 November 2020. https://mb.com.ph/2019/08/12/better-health-care-for-cancer-patients-ensured-as-cancer-laws-irr-signed/

[5] Que J, Sy Ortin TT, Anderson KO, Gonzalez-Suarez CB, Feeley T, Reyes-Gibby CC. Depressive Symptoms among Cancer Patients in a Philippine Tertiary Hospital: Prevalence, Factors, and Influence on Health-related Quality of Life. J Pall Med. 2013; 16:10. DOI: 10.1089/jpm. 2013.0022.

CASE STUDY

THAILAND

Clinic Founder: Pongparadee Chaudakshetrin, MD, anesthesiologist, formerly of Siriraj Hospital Pain Clinic in Bangkok, Thailand, and now at Samitivej Sukhumvit Hospital and Praram 9 Hospital

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) ranks Thailand as 47th in its global list of top-50 healthcare systems, primarily for its good universal healthcare system [1]. In 2017, the Thailand government set a 2026 strategic goal of becoming a world-class “Medical Hub.”[2]

Thai healthcare and its funding are divided into three schemes: government, nonprofit, and private. The Ministry of Public Health oversees policies, quality of practices, and execution of the government scheme introduced in 2001 to 2002 to ensure universal healthcare for the country’s 68 million citizens. This healthcare coverage scheme which was then called the ‘30-baht scheme’, offered comprehensive healthcare that included not just basics, but services such as radiotherapy, surgery, and critical care for accidents and emergencies. The scheme includes management of nearly 930 contracted public hospitals—many of whom carry international accreditations--and 9,768 clinics or health centers [3]. All receive funding generated by public tax revenues and distributed via the National Health Security Office according to local population size.

The government scheme is further broken down into three major programs: the universal coverage scheme, a welfare system for civil servants and their families, and Social Security for private employees only. A gold card is issued free to any Thai citizen who wants to access the universal care provided in their health district or to cover referrals to any out-of-area health specialists.

Although high-quality rural medical care is less assured than care provided in urban areas, most citizens can adequately access government-run healthcare.

Patient fees and private insurance fund 363 private hospitals and 25,615 private clinics [4], which tend to serve patients faster than the often-overloaded public health facilities. In addition to treating Thai nationals, private hospitals play a major role in Thailand’s thriving medical tourism [5], which is among the most respected in the world.

While general healthcare in Thailand has enjoyed strong government attention and investment, pain management specifically has not been a government priority.

Of all the conditions that cause pain, cancer pain appears to be most publicly acknowledged as a major health challenge in Thailand. A 2003 article [6] by Drs. Kittiphon Nagaviroj, MD, and Darin Jaturapatporn, MD, in Pain Research and Management revealed the scale of the problem. It noted that in-hospital admissions by cancer patients were rising and that of the 62% of admitted cancer patients who report experiencing pain [5], one-third received no pain management intervention [7].

Among cancer patients whose pain was chronic, approximately half reported receiving pain treatment, but often only with simple analgesics [8]. This may be because one study at a Thai teaching hospital found that nearly 60 percent of recently graduated physicians and residents in 2005 acknowledged that they did not know how to administer pain medication, and more than half feared that terminal cancer patients would become tolerant or addicted to any provided opioids, and thus, had a generally negative attitude about pain management overall [9]. The same study found that 86.4% of physicians said they needed to take pain management courses [10].

Launching A Multidisciplinary Pain Clinic

In the late 1980s, Pongparadee Chaudakshetrin, MD, was assigned by the head of the anesthesiology department at Siriraj hospital to start a Pain service. At the time, there is no specific policy or direction plans but to diversify anesthesiologic roles in managing pain out of the operating theater. Service was managed in a small clinic for patients with both acute and chronic pain by a three-person staff (physician, nurse, assistant secretary) The pain management offered were evaluation, diagnosis, and management through the diagnostic and therapeutic intervention to address nearly every kind of pain, primarily through neural blockades and pharmacological treatments, including analgesic and psychotropic medications, and nerve stimulation. The operating hours were 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday. The patients were consulted but sometimes referred from other hospitals where there was no service running. Most of the problems were diagnosed with cancer and chronic pain.

When the patient completed the round of further consultations, clinic staff would communicate with all of the specialists, gathering insights and recommendations and, when possible, meeting with them as a larger team to discuss and agree on possible treatments and plans.

At the time, the pain condition and its management were not installed in the curriculum of the medical student. Only acute postoperative pain management was taught seldomly in the teaching round. A routine talk on ‘Pain Management’ for a group of medical students that rotated to the anesthesiology department was initiated as this new medical service was recognized as part of the Anesthesiology Department.

However, on the larger healthcare landscape at the time, only a few people were interested in pain management and treated the pain problem appropriately, especially chronic and cancer pain, but this was progressively changed. Dr. Chaudakshetrin was a vocal advocate for the Pain clinic, by her teaching and active participation in educational activities in and outside the Anesthesiology department, she worked closely with the other department staffs to try to inspire support and engagement of medical students including graduates in the field such as an anesthesiology resident and alliances.

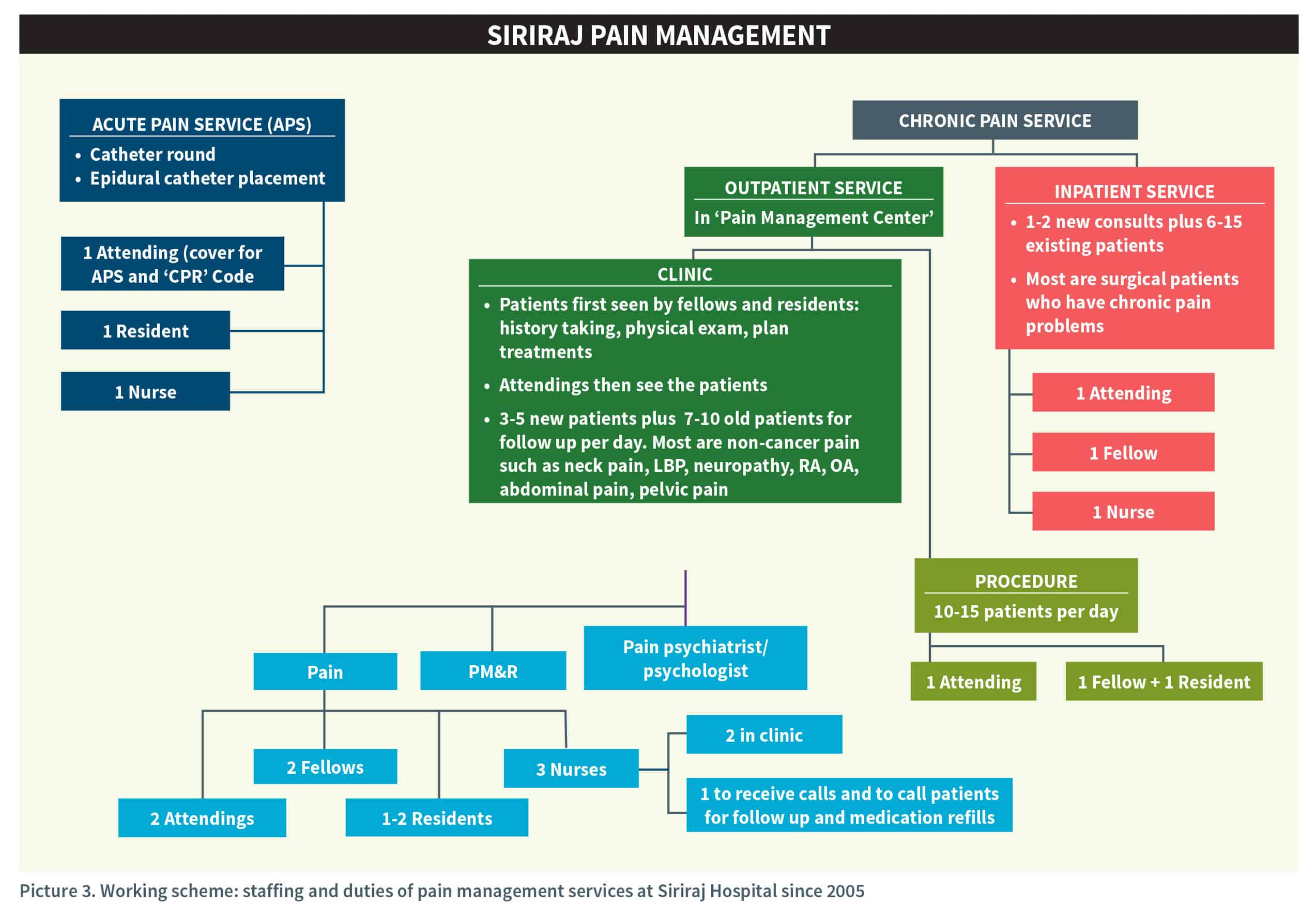

Her efforts and the support of the department director helped the clinic become more involved in the academic of the Department of Anesthesiology, which in turn strengthened support among hospital and university leaders. Interest further improved among hospital colleagues after clinic staff showed them how the facility was addressing problems associated with post-op suffering. As more anesthesiologists recognized the value of multidisciplinary treatment options, some tried to help the clinic. In 2005, the acute postoperative pain service established and separated which nudged Dr. Chaudakshetrin toward treating more on chronic pain patients and fellowship training program initiatives on pain management.

Based on such a highly urban area, Siriraj Hospital traditionally handled the highest volume of patients in the metropolitan area. The number of patients with difficult pain conditions grew progressively. The complexity of the overlapping pain conditions finally prompted the group to seek treatment alternatives. Clinic staff and hospital faculty began to look at a multidisciplinary team approach but moved forward cautiously. It was five more years before the hospital was ready to try an approach that united expertise and insights from diverse medical specialties.

Dr. Chaudakshetrin installed a patient assessment, diagnosis, and consultation process that would steadily evolve the service to a multidisciplinary clinic model. Only patients who considered difficult were cautiously treated through the comprehensive evaluation

and diagnosis by clinic staff (doctor and nurse) and then consulted to specialists who were involved in the managed care including psychiatrists, physiotherapists, and rehabilitationist.

When the patient completed the round of further consultations, clinic staff would communicate with all of the specialists, gathering insights and recommendations and, when possible, meeting with them as a larger team to discuss and agree on possible treatments and plans.

The patient then met with the group to hear a preliminary diagnosis, receive education on available treatments, and be asked for consent on the treatment plan. The clinic staff collaborated for follow-up and post-treatment evaluations.

PERSONNEL: Recruiting And Training a Multidisciplinary Pain Clinic Team

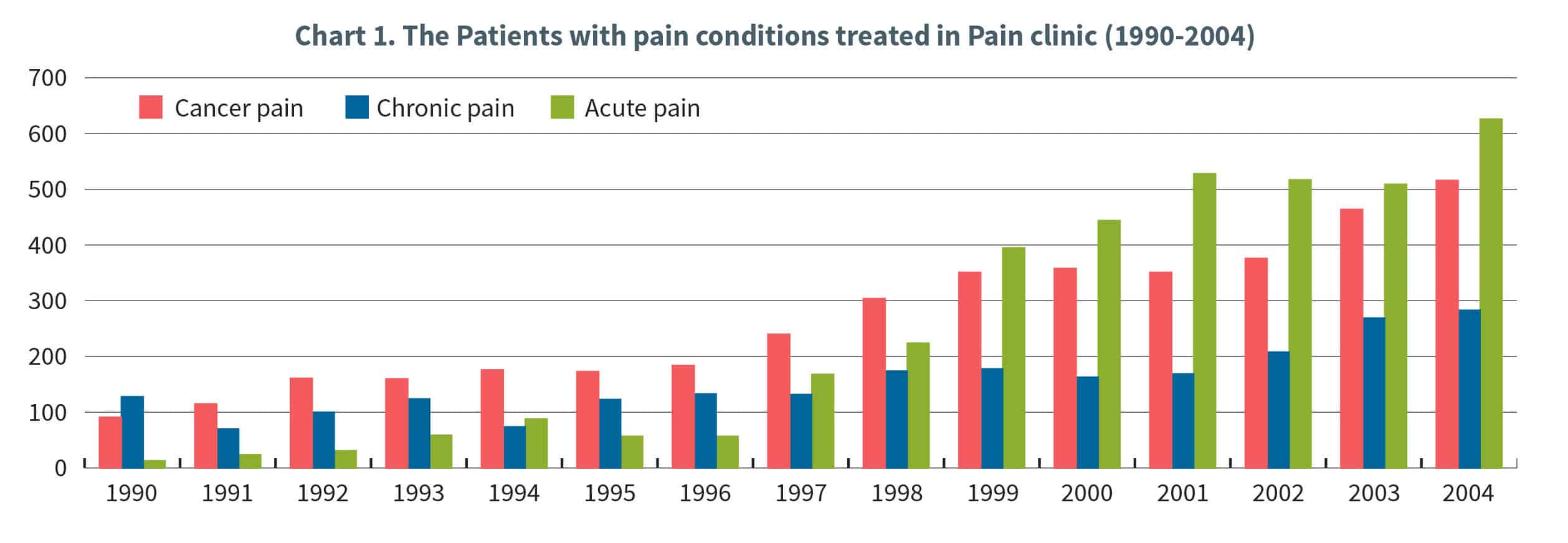

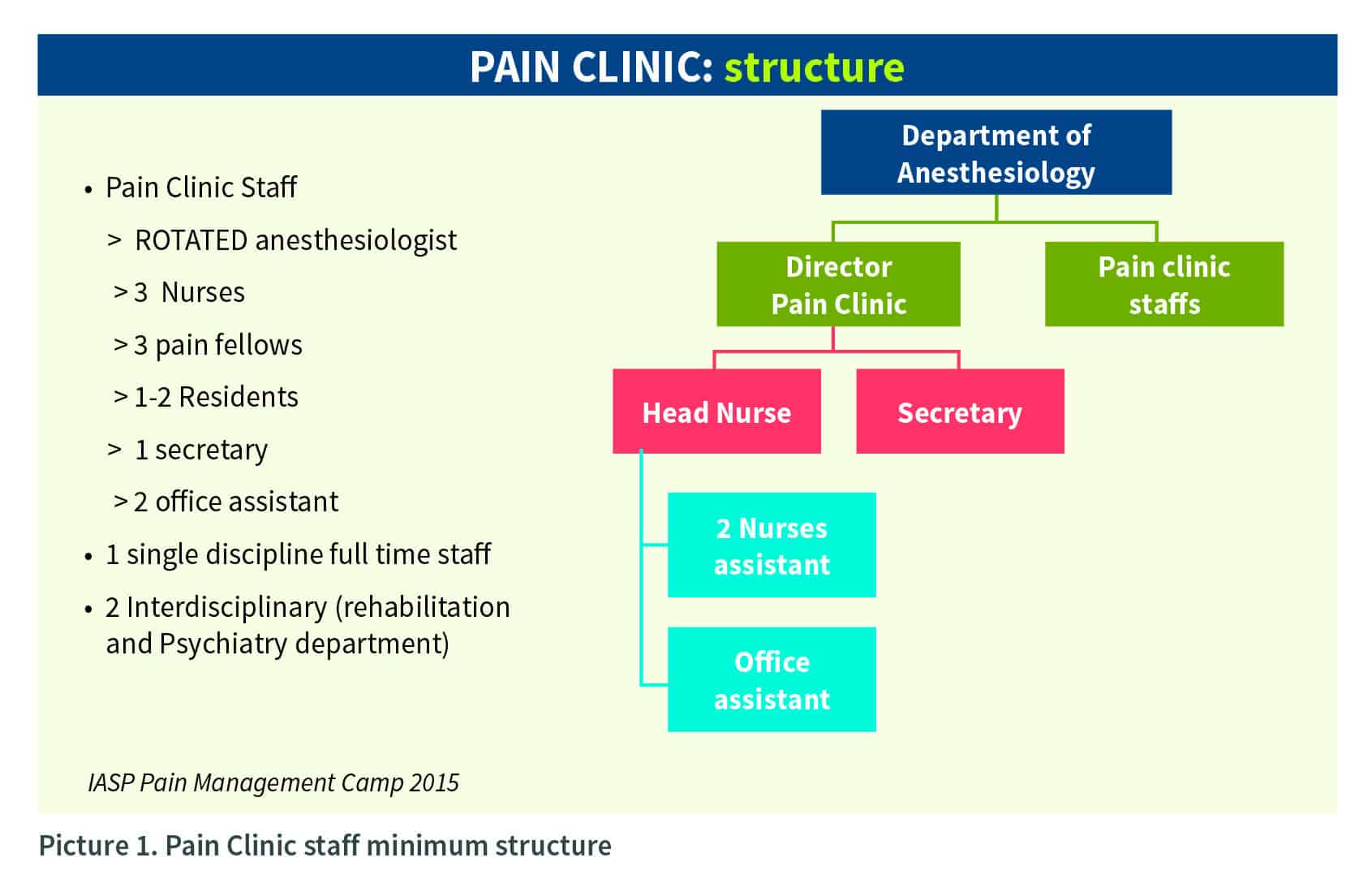

In its first year, the pain clinic served around 200 patients with an initial staff of three—Dr. Chaudakshetrin is the pain medicine physician, an assistant secretary, and a nurse. Full-time professional staffing stayed the same for three years. Until 1993, patient-demanding pain management service increased progressively, a second nursing staff was allocated enabling the clinic to serve more patients annually. By the time the hospital expanded the staff again with more nurses and assisting staff four years later, patient-visit numbers had reached an average of 1,000 a year.

For the next 13 years, patient growth flourished and totaled 5,000 patient-visits in 2010. By 2015, the hospital had slowly continued to expand clinic staff to two to three attending anesthesiologists, three registered pain nurses, one assistant secretary, three Thai fellows, two visiting international fellows, one volunteer physiatrist (Tuesdays only), and one volunteer psychiatrist (Thursdays only). Grand rounds for in- patient consultations occurred every two weeks, while staff conducted clinic pharmacological ward rounds each Tuesday. The staff did weekly intervention procedures in a single theater session on Wednesdays.

Although not assigned specifically to the clinic, when time allowed, a hospital pharmacist would visit the clinic to counsel clinic patients upon request whenever new medications were introduced or a negative drug reaction occurred. A social worker also provided financially and support assistance to clinic patients upon referral.

Especially in the early years, recruitment of talented, committed personnel for the clinic’s multidisciplinary team was difficult, despite the ever-increasing workload. The hospital structure was such that each employee was mandated to work only for his or her department.

Convincing a physician to see clinic patients meant asking the individual to spend hours working on a project that was under the oversight of the Department of Anesthesiology rather than his or her own.

Using her strong relationship-building skills, Dr. Chaudakshetrin reached out to personal friends and professional acquaintances to get involved and help her execute the MDPC model for the good of the patients. In one case, an interesting physiatrist (physical medicine and rehabilitation physician, PM&R) and a close friend volunteered every Tuesday morning for more than 20 years.

Dr. Chaudakshetrin worked to strengthen the clinic model by organizing an in-depth multidisciplinary pain meeting every month but would meet more frequently if complex cases arose. These get-togethers helped bond staff through a better understanding of each other and shared, self- taught knowledge that would help the clinic succeed.

Challenges: Personnel

The biggest staff challenge for the clinic was that people did not consider pain as a major health problem, so they did not want to be full-time pain management specialists nor to work full-time in an MDPC, according to Dr. Chaudakshetrin. A part-time schedule supporting staff was not fully dedicated to pain management, nor were they often willing to learn and improve their competency skills.

Besides, the hospital did not develop a succession plan for a pain management specialist in case Dr. Chaudakshetrin or the other pain specialist left. This all made personnel recruitment an ongoing concern.

Another major challenge was there was no pain treatment room; therefore, anesthetic pain treatment could not be scheduled. Normally, it was done in the recovery room or only when there was a vacancy in the operating theater, resulting in inadequate time and access to appropriate facilities for larger procedures.

Most of the time, clinic staffers were already scheduled to work in the pain clinic, but because the hospital considered pain a non-emergency, staff sometimes would be pulled away from clinic duties to work in operating rooms instead. This occasionally led to a severe shortage of clinic staff during the working day, according to Dr. Chaudakshetrin, and clinic patients were forced to suffer longer.

Personnel turnover at the higher, decision-making levels at the hospital also had negative impacts on clinic management and the addition of new services. Department head replacements were not always as supportive of the clinic, and personnel churn meant hospital policies were not always consistent. For example, despite growing numbers of patients and workload, supporting staff would not be assigned to help.

Training and Troubleshooting

Ongoing training of personnel was critical throughout the clinic’s evolution. Dr. Chaudakshetrin trained her nurses and assistants because, in the early 1990s, the university and hospital did not have any pain management courses for nurses.

As a clinic administrator, Dr. Chaudakshetrin had already worked to improve education to meet department standards even before the transition was made to a multidisciplinary approach. Thus, the Department of Anesthesiology provided some training for her administrating staff, but most learnings of clinic staff occurred on the job and alongside Dr. Chaudakshetrin, watching her listen carefully, speak to patients, and handle patient cases.

Personal relationships continued to play a vital role in recruiting and training multidisciplinary staff. In the clinic’s foundational years, Dr. Chaudakshetrin developed friendships and sometimes gave presentations alongside four specialists--a psychiatrist, a rheumatologist, a rehabilitation specialist, and an orthopedic surgeon--whom she met at professional conferences and pain management symposia. Their common interest inspired them to work together more consistently, and the friends would refer to medical students and fellows to work or volunteer regularly in the clinic. This support helped strengthen and expand the multidisciplinary team.

The clinic staff worked hard to improve core competencies needed to optimize the outcomes of the MDPC. These included a strict focus on accurate pain diagnoses and management, along with basic communication and listening skills. Because communication was considered the most important of clinic skills, all staff were required to excel at discussing, training, and especially listening to patients, other hospital staff, and interdisciplinary consulting staff.

One skill lacking at the clinic in its early days was a staff member proficient in statistics. While a basic knowledge of statistics would have helped develop clinic-based research, the nurses in the 1990s did not have time or training to conduct possible research.

To Dr. Chaudakshetrin, delivering pain training and education was one of the most important elements of clinic operations. Healthcare providers from other hospital departments would sometimes visit to observe, and she advocated for the establishment of a residency training program. Support from the department improved once the clinic—thanks in part to ongoing training by volunteer specialists--had built a strong positive reputation among patients, her peers, and the wider community.

FACILITIES

The Multidisciplinary Pain Clinic Environment

Because the MDPC resided in the hospital, it had to use existing space. Initially, only one room of approximately 4 square meters was allocated in the rehabilitation building for clinic work. She and the assigned nurse eventually moved to two rooms and slightly larger hospital accommodations of 8X10 square meters to see patients for pain assessment, follow-ups, and small procedures such as diagnostic nerve blocks for patients with upper-arm pain.

Finding time and space to administer larger nerve blocks was an ongoing challenge since that required competing for the use of operating theaters. The tight scheduling of theater rooms meant finding vacancies for every clinic patient at the needed times was nearly impossible; if operations were scheduled for 9 a.m., Dr. Chaudakshetrin and her assistants would arrive early at 8 a.m. to fill the narrow time slot with clinic patient procedures. The competition for operating space meant scheduling required extreme flexibility. Eventually, the situation resolved, but it took years before people recognized that the MDPC staff was acting only in the best interest of its patients.

Between 1992 and 1997, the clinic acquired space of 80 square meters and received two infusion pumps and a PCA machine to bolster its development of anesthetic acute pain services. It remained in that space until 2011 when the MDPC was permitted to expand exponentially. The new facility had a waiting room, seven clinic rooms for assessment and treatments, and a small meeting room with a display board that worked well for teaching, pain self-management training, and meetings of the multidisciplinary team or families. The clinic remains at this site today.

In terms of equipment, “nothing fancy” was required when she transitioned from a traditional to a multidisciplinary pain clinic, according to Dr. Chaudakshetrin. The hospital supplied basic equipment to the pain clinic such as that used to establish pain scores and conduct physical and neurological exams. Other equipment such as a C-arm had to be borrowed from other departments. The equipment also was sometimes added based on which type of specialist was working in the clinic or which patient conditions were most common. Some specialists even had their equipment such as demonstration charts of physical exercises for patients to do at home.

The Multidisciplinary Pain Clinic Funding Model