Pain in Refugee and Displaced Populations

Authors

- Amanda C de C Williams, PhD: University College London, UK

- Lester E Jones, PhD: Singapore Institute of Technology, Singapore

- Jordi Miró, PhD: University Rovira i Virgili, Spain

Pain is often neglected and undertreated in vulnerable populations, including refugees and people who have been displaced, often to neighbouring low- or middle-income countries. Even those in high-income host countries with robust healthcare systems face significant barriers to adequate pain assessment and treatment.

The Situation of Refugees and Displaced People

Displaced people flee their homes due to conflict, persecution, or environmental disasters, in which they may lose family members, homes, livelihoods, and legal status. These traumatic experiences are compounded by precarious living conditions, such as life in refugee camps, where even basic necessities such as accommodation and food are often insufficient. If, in high-income countries, refugees and asylum seekers may also face difficulties such as uncertain legal and financial status, temporary housing, limits on work and, in some cases, detention. Navigating unfamiliar and complex healthcare systems adds to these challenges.

Many displaced individuals are survivors of severe human rights violations, including torture. However, torture is often not disclosed due to factors such as distrust, language barriers, feelings of shame, traumatic stress, and other personal or cultural reasons. Survivors of torture commonly experience a constellation of symptoms including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety. These symptoms interact with pain to create complex and disabling chronic conditions [1]. Social isolation and the lack of family support may significantly worsen the experience of pain in refugee populations.

Pain in refugees is often complex, corresponding poorly to the history of injury or underlying pathology. Thorough assessment is crucial because of the higher likelihood of untreated but potentially treatable conditions. Beliefs of the person with pain on its cause(s) may differ significantly from those of healthcare providers. Although there may be no apparent recognition of a psychological component to pain, by the person with pain or the healthcare provider, it may be implied in non-psychological language in some cultural models of ill health and pain [1].

Pain care for displaced people

Availability of specialist pain services in host countries varies widely; many have none. In refugee camps, healthcare is often focused primarily on emergency medicine, which may include psychiatric or psychological services. These services are typically equipped to address pain with clear pathoanatomical causes, but rarely have the expertise, resources, or infrastructure to manage more complex pain. Additionally, psychiatric and psychological services provided by aid organizations from high-income countries may emphasize post-traumatic stress at the expense of other health concerns, and may label pain as “psychosomatic,” precluding adequate investigation or treatment of pain conditions.

Evidence on effective pain treatment in refugees remains limited, particularly in children and adolescents [6]. In the absence of robust data, best practices for assessment and treatment should be followed, but with specific considerations: providing clear and culturally sensitive explanations of pain; ensuring fully informed consent (as technology and practices may be unfamiliar or intimidating); and recognizing the possibility of medical conditions that are prevalent in low-income countries but rarely encountered in the host country [1, 5].

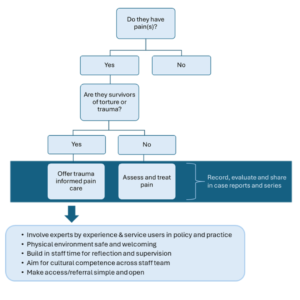

Clinicians should ask about pain without waiting for patients to raise it [7; Figure 1]. This process may require interpreters, visual aids such as body diagrams for clear communication, and extra time to ensure accurate understanding. Clinicians should also inquire about patients’ experiences, including the circumstances surrounding their displacement, such as the loss of loved ones, homes, and belongings, and their journey, often marked by significant hardship, violence, and trauma [1,7]. Pain often holds complex and culturally specific meanings, making it essential to approach treatment goals with sensitivity, taking into account personal, cultural, spiritual, and health beliefs. Refugees and displaced people should be involved in planning their healthcare to avoid perpetuating colonial attitudes on needs and solutions.

Where torture is suspected, clinicians need to explore sensitively, aiming to build trust: torture undermines trust, and in some cases, healthcare staff have been implicated in a person’s torture. [3,4]. Building trust requires clarity about confidentiality, particularly in situations where healthcare providers may be required to collect and share information about civil status or entitlement to health services with immigration authorities.

Physical therapy is often the most culturally acceptable treatment for pain. Hands-on physiotherapy can help to rebuild trust and foster engagement when implemented with psychologically-informed or trauma-informed principles [2,5]. Psychiatric and psychological clinicians, doctors, and nurses in refugee camps should train in pain assessment and management, enabling them to offer evidence-based support for individuals in these vulnerable populations.

There is a pressing need for research, including case studies, to better understand pain management as well as long-term adaptation and rehabilitation with or without treatment.

References

- Amris K, Jones LE, Williams ACdeC. Pain from torture: assessment and management. Pain Reports 2019;4(6):e794. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6903341/

- Dee JM, Gell N, van Eeghen C, Littenberg B. Physical therapy for survivors of torture: a scoping review. Torture Journal 2024;34(1):113-27. https://tidsskrift.dk/torture-journal/article/view/138985/188965

- Haoussou K. When your patient is a survivor of torture. Br Med J 2016;355:i5019. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i5019

- Kaur G. Chronic pain in refugee torture survivors. J Global Health 2017;7(2):010303. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5804708/

- McGowan E, Beamish N, Stokes E, Lowe R. Core competencies for physiotherapists working with refugees: a scoping review. Physiotherapy. 2020 Sep 1;108:10-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2020.04.004

- Roman-Juan J, Sánchez-Rodríguez E, Solé E, Castarlenas E, Jensen MP, Miró J. Immigration background as a risk factor of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain in children and adolescents: differences as a function of age. Pain 2024;165(6):1372-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38189183/

- Williams AD, Hughes J. Improving the assessment and treatment of pain in torture survivors. BJA Education 2020;20(4):133-8. https://www.bjaed.org/article/S2058-5349(20)30003-2/fulltext