Sex and Gender

Biomedical understandings of sex and gender have traditionally been centered around a binary framework, conceptualizing sex as either male or female and gender as either man or woman. However, this restrictive framework fails to capture the diverse nature of identities. It overlooks the multiplicity of ways in which individuals express their sex and gender beyond the confines of a binary. These binary biomedical frameworks risk homogenizing peoples’ experiences while silencing the experiences of those who do not fit into these predetermined classifications. These binary frameworks therefore perpetuate inequities in healthcare more broadly, and in pain medicine more specifically.

The way sex and gender are conceptualized require nuanced and dynamic discourses that marry biological and sociocultural dimensions. Sex has traditionally been defined as a biological construct based on anatomy and genetics. However, the way in which we define sex based on biology needs to be more nuanced, considering organs, reproduction, chromosomes, gene expression, and hormonal levels. Sex is therefore best understood as a spectrum. Although non-all-exhaustive, some sex classifications include female, male, intersex, and disorders of sexual development. Gender has been defined as socially constructed, taking into account the multifaceted sociocultural, psychological, and experiential dimensions. However, multiple gender theorists conceptualize gender slightly differently. Although non-all-exhaustive, some gender identity classifications include: Two-Spirit, woman, man, transfeminine, transmasculine, transwoman, transmasculine, gender diverse, gender non-binary, agender, etc.

The ways that sex and gender are conceptualized are nuanced and continue to evolve in response to societal attitudes and advances in medicine. Sex and gender diversity are not monolithic; inclusive and intersectional approaches to understanding sex and gender beyond the binary are crucial within pain medicine. Considering that not all transgender and gender diverse (TGD) people will undergo medical and surgical gender-affirming care, understanding where each TGD person is in their journey is of utmost importance in supplying patient-centered care.

Pain beyond the binary

Rates of transgender and gender diverse (TGD) individuals presenting at pain clinics are rising, which is not surprising given the abundance of literature to suggest unique pain experiences in this population.

Empirical evidence of the co-occurrence of pain and gender diversity is available but limited:

- Current estimates of chronic or widespread pain in TGD or sexual and gender minority (SGM) adults range from 14.8 to 56.4% [1-2]

- In the United States, TGD Medicare beneficiaries under the age of 65 are shown to have more chronic conditions than cisgender Medicare beneficiaries, including disabling mental health and neurological/chronic pain conditions [3].

- High rates of chronic pain are also found in TGD youth worldwide; a recent cross-national, retrospective study found that one third of adolescents identifying as non-binary reported suffering from pain all or most of the time over 12-months [4].

- One study reviewed the number of TGD youth attending a pediatric intensive interdisciplinary pain treatment program in the United States and found a prevalence rate of 6.11% over a 4-year period. Notably, the TGD youth in this sample were least likely to complete the program and presented as more emotionally distressed and functionally impaired at baseline compared to age-matched, cisgender peers [5]

- Research suggests that rates of autism diagnoses and autistic traits are higher in gender diverse individuals compared to the general population [6], which, for this subset of people, can exacerbate risk of pain or contribute to its undermanagement. For example, a retrospective review of electronic medical records found that a total of 30% of patients in the outpatient pediatric pain clinic were found to likely meet criteria for autism, with 9% having a prior diagnosis and an additional 21% identified during clinical assessment. Among the autistic youth, 52% presented with widespread pain and 6% identified as gender expansive or transgender.

Biological and Sociocultural Considerations

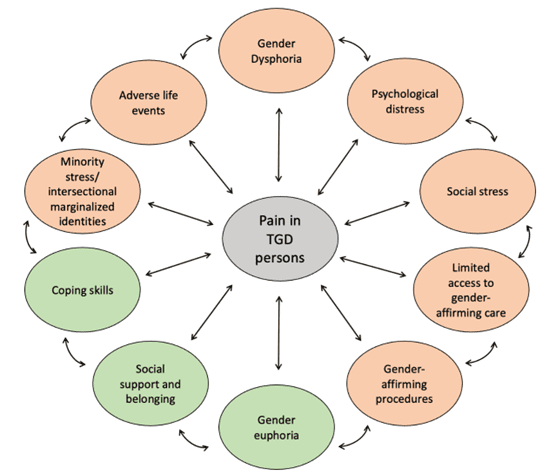

Figure 1. Factors known to inform pain experiences in TGD individuals. Arrows are used to indicate the interacting nature of these factors. Potential risk factors are denoted in orange and potential resilience factors are denoted in green.

Higher rates of pain in TGD individuals may be linked to the experiences associated with one’s gender identity. This phenomenon can be explained by the gender minority stress framework, which suggests that TGD individuals face unique stressors due to their minority status, leading to higher risks of negative health outcomes, while resilience factors like positive self-identity can mitigate these effects [7]. Stressors are categorized into distal stressors, such as discrimination and victimization, and proximal stressors, like internalized transphobia and fear of rejection. The impact of stressors can be exacerbated by development and intersectional identities [8]. Figure 1 presents may of the key factors known to uniquely influence pain experiences in TGD individuals. However, the relative impact of these factors are not mutually exclusive and cannot be quantified; factors impacting pain experiences in gender diverse youth are interconnected, interact with, and influence each other (e.g., adverse childhood experiences and social stress may be related and influence psychological distress; gender dysphoria is characterized by psychological distress). In this section, we provide examples of research that points to the relevance of the purported risk and resilience factors.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

- ACEs are a known risk factor for pain and tends to be common are higher amongst TGD compared to cis-gender individuals, especially in terms of emotional abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect [9].

- Amongst adults with chronic pain, TGD participants reported higher ACE scores and current pain scores compared to cisgender individuals [10].

Gender Dysphoria

- Gender dysphoria refers to the distress that may accompany gender incongruence, often heightened at the onset of puberty, and is associated with minority stress across systemic (e.g., discrimination), familial (e.g., conflict, rejection), social (e.g., bulling, exclusion, harassment, transphobia), and psychological (e.g., anxiety, depression, internalized transphobia) domains.

- Only one study characterized pain in a sample of eight youth with gender dysphoria presenting at a chronic pain clinic. This study found that that all eight patients treated for both chronic pain and gender dysphoria experienced a consistent reduction in their pain scores over time [11].

Social Stress

- Social stress, stemming from discrimination, stigma, and limited healthcare access, significantly exacerbates chronic pain in TGD individuals through prolonged exposure to stress hormones, which can alter immune function and promote inflammation, contributing to heightened pain sensitivity and chronic pain [12].

- Based on survey data of parents of TGD youth, about 0.6 million youth in the U.S. have experienced discrimination; these children are twice as likely to have chronic pain [13].

Psychological Distress

- Research shows that TGD individuals are at a greater risk of poor psychological well-being, with transgender women being at the greatest risk [14]. Given the link between pain severity and prevalence with impairments in mental health, higher psychological distress is believed to be a mechanism of worsened pain outcomes in TGD individuals [15, 16].

Gender-affirming (Biomedical) Interventions

- Sex hormones (estrogens, progesterones, androgens, testosterones) play pivotal roles in pain perception and transmission. Differences in pain sensitivity have been documented between cisgender women and men, where women have been noted to have greater sensitivity compared to their men counterparts. However, evidence in cis-gender people cannot be extrapolated to TGD people as it is necessary to consider gender-affirming hormonal impacts and mental health impacts of gender dys/eu-phoria. Differences in pain sensitivity in people who self-identify as TGD (outside of animal models) are less well documented but exists as follows:

- A few studies show that transgender people reported a higher prevalence of pain related to gender-affirming hormones (GAHs). For example, studies show approximately 30% of transwomen reported experiencing painful conditions, commonly in the breast and head, and 80% of these transwomen expressed that these painful conditions occurred after having started GAHs. On the contrary, 60% of transmen on GAH had improvement of their chronic headache [17, 18].

- Other research shows that approximately 69% of transmen endorsed abdominopelvic pain following initiation of testosterone and 51% of transmen reported pain with sexual penetration, with pain being present in only 42% of these men prior to testosterone use [19, 20].

- The above-mentioned research is in adults. In youth, less is known is if gonadotropin releasing hormone injection is associated with altered pain syndrome and/or injection site pain.

- Some TGD people may choose to undergo any number of gender-affirming surgeries (GAS) to align their bodily appearance with their gender identity, simplistically categorized as “feminizing surgery” and “masculinizing surgery”, or “top surgery” and “bottom surgery”. With any type of surgery, chronic pain can be a potential side effect; but the degree to which one experiences persistent pain is contingent on the intensity of the postoperative acute pain, pre-existing chronic pain, and depression and anxiety. Research on post-surgical pain in transgender people is lacking, but suggestions:

- Transgender patients receiving pectoralis nerve blocks reported lower pain scores than cis-gender patients undergoing breast reduction surgery [21].

- Robinson et al. revealed no difference in opioid consumption in patients undergoing top surgery compared to patients undergoing oncologic mastectomy without immediate reconstruction, both of whom received pectoralis nerve blocks [22].

Protective Factors: Gender Euphoria, Social Belonging, and Coping Skills

- Gender-affirming care and acceptance are critical to pain management as research shows that when TGD individuals can live in alignment with their gender identity, it can be a powerfully positive experience (i.e., gender euphoria), embodiment of one’s gender identity, and stronger sense of self, which may buffer against pain-related stressors or facilitate coping with pain related to gender-affirming practices.

- Gender euphoria also alters TGD peoples’ pain experiences. TGD people experience fewer phantom penises and fantom breasts after gender-affirmation surgery than their cis-gender counterparts [23]. Furthermore, transmen use less opioids and experience less pain after breast removal surgery [24].

- Resilience factors related to enhancing self-acceptance, hope, community connections, and positive self-identification can help TGD individuals cope with stressors. For example, supportive families, communities, and schools, as well as gender-affirming healthcare, have been found to be crucial in developing coping skills that protect against negative mental health outcomes and enhance overall well-being.

Practice Points for Healthcare Providers

- Seek out resources specific to providing care for gender-diverse patients within your area of practice, such as published guidelines for anesthesia [25], gastroenterology [26], psychology [27], as well as general resources for practitioners and families

- Create an affirming, welcoming environment in your clinical space, which can include access to gender-neutral washrooms, inclusive options on intake forms and clinic documentation, displaying safe space stickers, avoiding gendered materials, etc.

- Clinical staff should introduce/display their own pronouns, and ask patients for theirs

- Consider privacy and safety when asking about and documenting gender-related information (e.g., for an adolescent, is this information known to their parent? Has the patient consented to this information being documented visibly in their medical chart?)

- Ask only questions that are relevant for the care you are providing, and educate yourself about issues specific to gender-diverse people that may impact pain care (e.g., influence of hormone treatments, pain associated with chest binding or genital tucking, understanding where an individual is in their gender exploration/understanding etc.)

- Remember that each individual is unique, and do not assume what experiences (medical or social) an individual has had based on their gender identity

- Apologize if you make a mistake

- Be aware of the minority stressors impacting gender-diverse individuals in your area of practice, particularly if there is legislation restricting access to gender-affirming care, or exposure to transphobic violence. Mental health providers and referrals to support groups, queer communities, and other sources of allyship may help buffer against internalized transphobia and negative self-evaluation and increase identity pride.

- Understand that gender diversity is one part of a person’s experience, and be aware of biases in healthcare that inappropriately attribute health issues to gender in TGD individuals

- Prioritize patient safety, autonomy, and respect

Practice Points for Researchers

- Be aware of existing guidelines on the ethical conduct of research in transgender and gender-diverse populations [28-30]

- Review guidance on conducting sex- and gender-sensitive research in pain [31], and consider how to incorporate gender-inclusive practices in all research, regardless of whether the focus is on TGD individuals. For example, use inclusive language when addressing groups of people (e.g., “folks” or “everyone” instead of “ladies and gentlemen”)

- Ensure that research on TGD individuals is done in partnership with TGD communities from inception to dissemination, and that cisgender researchers reflect on their position, power, and biases [32]

- Understand the additional risks faced by TGD individuals with respect to privacy and confidentiality, and account for this in developing safe and autonomy-promoting research practices

- Avoid damage- or deficit-focused research [33]

References:

- Levit, D., Yaish, I., Shtrozberg, S., Aloush, V., Greenman, Y., & Ablin, J. N. (2021). Pain and transition: evaluating fibromyalgia in transgender individuals. Clin Exp Rheumatol, 39(Suppl 130), 27-32.

- Chadwick, A. L., Lisha, N. E., Lubensky, M. E., Dastur, Z., Lunn, M. R., Obedin-Maliver, J., & Flentje, A. (2024). Localized and widespread chronic pain in sexual and gender minority people—an analysis of the PRIDE study. Pain Medicine, pnae023.

- Dragon, C. N., Guerino, P., Ewald, E., & Laffan, A. M. (2017). Transgender Medicare beneficiaries and chronic conditions: exploring fee-for-service claims data. LGBT health, 4(6), 404-411.

- Johansson, C., Kullgren, C., Bador, K., & Kerekes, N. (2022). Gender non-binary adolescents’ somatic and mental health throughout 2020. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 993568.

- Scheurich, J. A., Sim, L. A., Gonzalez, C. A., Weiss, K. E., Dokken, P. J., Willette, A. T., & Harbeck-Weber, C. (2024). Gender Diversity Among Youth Attending an Intensive Interdisciplinary Pain Treatment Program. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 1-11.

- Kallitsounaki, A., & Williams, D. M. (2023). Autism spectrum disorder and gender dysphoria/incongruence. A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53(8), 3103-3117.

- Delozier, A. M., Kamody, R. C., Rodgers, S., & Chen, D. (2020). Health disparities in transgender and gender expansive adolescents: A topical review from a minority stress framework. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 45(8), 842-847.

- Boerner, K. E., Keogh, E., Inkster, A. M., Nahman-Averbuch, H., & Oberlander, T. F. (2024). A developmental framework for understanding the influence of sex and gender on health: Pediatric pain as an exemplar. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 105546.

- Schnarrs, P. W., Stone, A. L., Salcido Jr, R., Baldwin, A., Georgiou, C., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2019). Differences in adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and quality of physical and mental health between transgender and cisgender sexual minorities. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 119, 1-6.

- Shirsat, N., Finney, N., Strutner, S., Rinehart, J., Elliott III, K. H., & Shah, S. (2022). Characterizing Chronic Pain and Adverse Childhood Experiences in the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, or Queer Community. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 10-1213.

- Sayeem, M., Carter, B., Phulwani, P., & Zempsky, W. T. (2021). Gender dysphoria and chronic pain in youth. Pediatrics, 148(4).

- Anger, J. T., Case, L. K., Baranowski, A. P., Berger, A., Craft, R. M., Damitz, L. A., … & Yaksh, T. L. (2024). Pain mechanisms in the transgender individual: a review. Frontiers in Pain Research, 5, 1241015.

- Weiss, K. E., Li, R., Chen, D., Palermo, T. M., Scheurich, J. A., & Groenewald, C. B. (2024). Sexual orientation/gender identity discrimination and chronic pain in children: a national study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

- Warren, J. C., Smalley, K. B., & Barefoot, K. N. (2016). Psychological well-being among transgender and genderqueer individuals. International Journal of Transgenderism, 17(3-4), 114-123.

- Boerner, K. E., Harrison, L. E., Battison, E. A., Murphy, C., & Wilson, A. C. (2023). Topical review: acute and chronic pain experiences in transgender and gender-diverse youth. Journal of pediatric psychology, 48(12), 984-991.

- Wurm, M., Högström, J., Tillfors, M., Lindståhl, M., & Norell, A. (2024). An exploratory study of stressors, mental health, insomnia, and pain in cisgender girls, cisgender boys, and transgender and gender diverse (TGD) youth. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology.

- Pain and transition: evaluating fibromyalgia in transgender individuals

- Aloisi AM, Bachiocco V, Costantino A, Stefani R, Ceccarelli I, Bertaccini A, et al. Cross-sex hormone administration changes pain in transsexual women and men. Pain. (2007) 132(Suppl 1):S60–S7. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.02.006.

- Goetsch MF, Ribbink PJA. Penetrative genital pain in transgender men using testosterone: a survey study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2022) 226(2):264–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.09.019.

- Grimstad FW, Boskey E, Grey M. New-onset abdominopelvic pain after initiation of testosterone therapy among trans-masculine persons: a community-based exploratory survey. LGBT Health. (2020) 7(5):248–53. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2019.0258.

- Miaskowski C, Paul SM, Cooper B, West C, Levine JD, Elboim C, et al. Identification of patient subgroups and risk factors for persistent arm/shoulder pain following breast cancer surgery. Eur J Oncol Nurs. (2014) 18(3):242–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2013.12.002.

- Robinson KA, Duncan S, Austrie J, Fleishman A, Tobias A, Hopwood RA, et al. Opioid consumption after gender-affirming mastectomy and two other breast surgeries. J Surg Res. (2020) 251:33–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2019.12.043.

- Ramachandran VS, McGeoch PD. Phantom penises in transsexuals. J Conscious Stud. (2008) 15(1):5–16. Available online at: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2008- 15313-001 (Accessed February 2, 2022).

- Ramachandran VS, McGeoch PD. Occurrence of phantom genitalia after gender reassignment surgery. Med Hypotheses. (2007) 69(5):1001–3. doi: 10.1016/j. Mehy.2007.02.024

- Verdecchia N, Grunwaldt L, Visoiu M. Pain outcomes following mastectomy or bilateral breast reduction for transgender and nontransgender patients who received pectoralis nerve blocks. Paediatr Anaesth. (2020) 30(9):1049–50. doi: 10.1111/pan.13969.

- Tollinche LE, Walters CB, Radix A, Long M, Galante L, Goldstein ZG, Kapinos Y, Yeoh C. The Perioperative Care of the Transgender Patient. Anesthesia & Analgesia (2018) 127(2): 359-366. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000003371

- Velez C, Newman KL, Paul S, Berli JU, Tangpricha V, Targownik LE. Approaching digestive health care in transgender and gender-diverse communities. Gastroenterology (2024) 166(3): 369-375.

- Coyne CA, Huit TZ, Janssen A, Chen D. Supporting the mental health of transgender and gender-diverse youth. Pediatric Annals (2023) 52(12): e546-e461.

- Adams N, Pearce R, Veale J, Radix A, Castro D, Sarkar A, Thom KC. Guidance and ethical considerations for undertaking transgender health research and institutional review boards adjudicating this research. Transgender Health (2017) 2(1)

- Bauer, G., Devor, A., heinz, m., Marshall, Z., Pullen Sansfaçon, A., Pyne, J, for the CPATH Research Committee. (2019). CPATH Ethical Guidelines for Research Involving Transgender People & Communities. Canada: Canadian Professional Association for Transgender Health. Available at http://cpath.ca/en/resources/

- Servais, J., Vanhoutte, B., Maddy, H., & Godin, I. (2024). Ethical and methodological challenges conducting participative research with transgender and gender-diverse young people: a systematic review. International Journal of Transgender Health, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2024.2323524

- Keogh E, Boerner KE. Challenges with embeddiing an integated sex and gender perspective into pain research: recommendations and opporutnities. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity (2024) 117: 112-121.

- Rogers M, brown C. Critical ethical reflexivity (CER) in feminist narrative inquiry: reflections from cis researchers doing social work research with trans and non-binary people, International Journal of Social Research Methodology (2024), 27:4, 447-461, DOI: 10.1080/13645579.2023.2187007

- Holloway BT. Highlighting Trans Joy: A Call to Practitioners, Researchers, and Educators. Health Promotion Practice. 2023;24(4):612-614. doi:10.1177/15248399231152468