Advertisers and marketers make a living out of grabbing your attention. They are not above using sudden loud noises (a salient physical stimulus or bottom-up attention grab). Nor do they shy away from top-down effects such as priming (defined as subtle suggestions made to the ‘subconscious’ brain to influence behaviour). But wait. Don’t classical models of attentional control depict a dichotomy of ‘top-down’ versus ‘bottom-up’ control and don’t we presume that the ‘top-down’ control is conscious and voluntary? Most of the time we like to think we’re in control of our actions; that we choose our goals and make headway towards them by following a cunning plan (top-down control of attention). It’s part of the human condition. To this end we like to think that the brain driven (top-down) control of attention is conscious and voluntary and we presume that brain driven control of attention is equivalent to ‘goal driven selection’. But how true is this premise?

Awh and colleagues [1] have recently considered this question and reviewed the mounting body of evidence that reports a gap between brain driven attentional control and goal driven selection. The review considers two factors: selection history and reward history. Here’s a brief summary:

Selection History:

Under experimental conditions [4], participants responded faster to blocks of targets with one defining feature (e.g. red) than mixed blocks when target defining features vary from task to task (e.g. red or vertical). Although this outcome is frequently explained by the effects of focussing attention in one direction only (i.e. less cognitive load and a higher fidelity top down signal when picking only one feature), Awh et al [1] make the point that it could also be due to the effects of INVOLUNTARY priming. That is, there is an automatic influence directing behaviour towards a feature that has been previously presented. A seminal study [3] that demonstrated more efficient searching for a target when the target was previously defined by a given feature has labelled this phenomenon ‘pop-out priming’.

Reward History:

As all parents know, a little bit of bribery to get the desired behaviour can be very effective. Something more to consider about rewarding behaviour is that there may be lingering effects. Once reward has taken place behaviour can be (automatically) biased towards previously rewarded items. An example of this is an experiment where participants received a large reward for their first choice of colour (red) and were then asked to switch the target colour from red to green to get a large reward on the next turn. Switching colour made them respond more slowly than they did on the few trials where the target colour stayed the same [2]. That is, being rewarded for one target INVOLUNTARILY biases you to seek that target more quickly the next time and confounds attempts to switch to a new target.

Summary

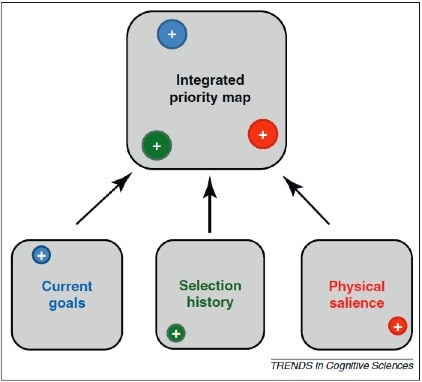

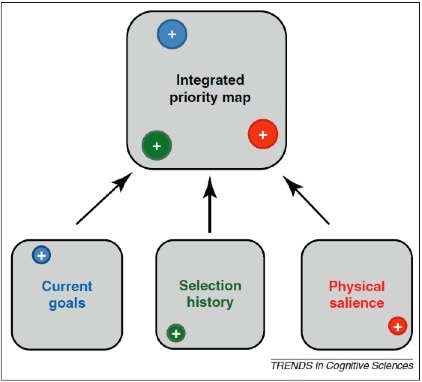

The upshot of these findings is that as well as the voluntary component involved in choosing current goals and directing attention towards attaining them, there are automatic influences that don’t easily fit into the bottom-up/top-down attentional control model. Sole consideration of any source of bias as ‘top-down’, when it is not due to physical salience, places potentially distinct sources of bias under one big umbrella. This ultimately impedes discovery and interpretation of other processing mechanisms or contributions. Awh et al[1] suggest converting interpretation of findings about attentional control to a framework where “…selection history is integrated with current goals and physical salience to shape an integrated priority map.” ([1]p437). Included in the article are some ideas for study designs to separate the sources of bias (for further reading if you are interested). Here’s a cartoon of the framework ([1]p441.)

Now this is all new territory for me (and some of the terminology is scary – is it automatic or subconscious? Or could it be subcortical processing that biases us?). I would be very interested in your thoughts about the post and the framework. I have to say, my initial thoughts about the framework are that I am never happy with square boxes or unidirectional arrows when we are discussing the brain!

Carolyn Berryman

Carolyn has been teaching with the Noisters (Neuro Orthopaedic Institute) for the last 10 years and finally got herself into research via a very competitive post-graduate scholarship. Not that she has every stopped studying – she already has a masters in physiotherapy and in pain science – good luck fitting PhD onto the business card! What is Carolyn researching for her PhD? Based at the University of South Australia in Adelaide Carolyn is looking at neurophysiological profiles between chronic pain and PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder) during working memory tasks.

Carolyn has been teaching with the Noisters (Neuro Orthopaedic Institute) for the last 10 years and finally got herself into research via a very competitive post-graduate scholarship. Not that she has every stopped studying – she already has a masters in physiotherapy and in pain science – good luck fitting PhD onto the business card! What is Carolyn researching for her PhD? Based at the University of South Australia in Adelaide Carolyn is looking at neurophysiological profiles between chronic pain and PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder) during working memory tasks.

What does Carolyn do day to day? Apart from rearranging the flowers on her desk and making room for Russian caravan tea from Abby, she’s onto the design of three studies that aim to investigate cognitive function in a group of people that pay a great deal of attention to their internal state (hypervigilant). That means lots of reading and a good deal time submitting ethics proposals. Time away from the office is spent on an island 100km south of Adelaide, sailing, cooking and dreaming of the next holiday! Here is Carolyn talking more about the research she is doing.

References

[1] Awh E, Belopolsky AV, & Theeuwes J (2012). Top-down versus bottom-up attentional control: a failed theoretical dichotomy. Trends in cognitive sciences, 16 (8), 437-43 PMID: 22795563

[2] Hickey C, Chelazzi L, & Theeuwes J (2010). Reward guides vision when it’s your thing: trait reward-seeking in reward-mediated visual priming. PloS one, 5 (11) PMID: 21124893

[3] Maljkovic V, & Nakayama K (1994). Priming of pop-out: I. Role of features. Memory & cognition, 22 (6), 657-72 PMID: 7808275

[4] Wolfe JM, Butcher SJ, Lee C, & Hyle M (2003). Changing your mind: on the contributions of top-down and bottom-up guidance in visual search for feature singletons. Journal of experimental psychology. Human perception and performance, 29 (2), 483-502 PMID: 12760630