When I first entered an experimental pain laboratory, I had no idea what to expect. I was a newbie to the BiM lab, and acting as a pilot participant in a colleague’s experiment. My colleague sat me down, attached some electrodes to my arm, and asked me to tell him what I felt on a 0-100 NRS anchored at 0 with ‘no pain’ and 100 with ‘worst pain imaginable’. He gave me many, many stimulation trials, and I kept giving ‘0’. I could feel that he was ramping up the intensity but, even though I didn’t like the feeling the stimulation gave me, I couldn’t honestly call it ‘painful’. It was too dull, too tolerable, too not-quite-pain to be called ‘painful’. I was feeling a changing in intensity, but I was unable to report that: the response options of 0 (no pain) to 100 implied that as soon as I shifted above 0, I was reporting pain. It was frustrating, because my role as a participant was to report what I felt, but I couldn’t! That was the first time I considered that there is a whole range of sensory experience encapsulated within the ‘0’ on a conventional 0-100 NRS for pain. For a participant, being unable to express the change in non-painful intensity that one is feeling can be frustrating. At the same time, the researcher loses potentially valuable information by restricting the participant’s response options.

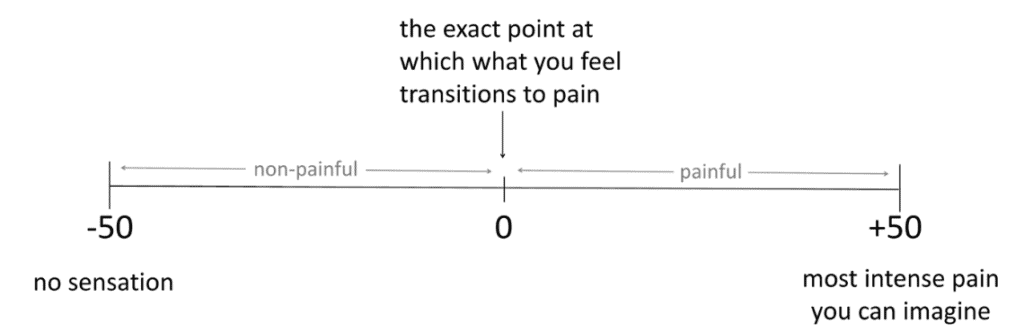

What about putting both non-painful and painful experiences onto a single scale? OK sure, it would violate the age-old traditions of psychophysiology, but it could be useful. We tentatively developed this ‘Sensation and Pain Rating Scale’ (SPARS) (Figure 1).

We piloted it to determine whether people intuitively preferred unequally or equally sized ranges for non-painful and painful, and to refine the anchors at either end. Next, we tested whether people use it in a way that made sense. In that experiment, people rated a bunch of laser stimuli on the SPARS and they did so in a way that made sense.

Then we spoke with the very knowledgeable Bob Coghill, who gets excited talking about pain assessment. That led to comparing how people use the SPARS to how they might use the two sides of the SPARS if they were presented separately. We chose a conventional NRS (0 = no pain; 100 = worst pain you can imagine) to represent the ‘painful’ end of the SPARS, and an invented ‘Sensation Rating Scale’ (SRS) (0 = no sensation; 100 = pain) to represent the non-painful end of the SPARS. In this Experiment 2, our participants rated a range of intensities of laser stimulation. In each block, they used only the SPARS, only the NRS, or only the SRS. We asked participants a whole heap of questions and we undertook a formal analysis.[1]

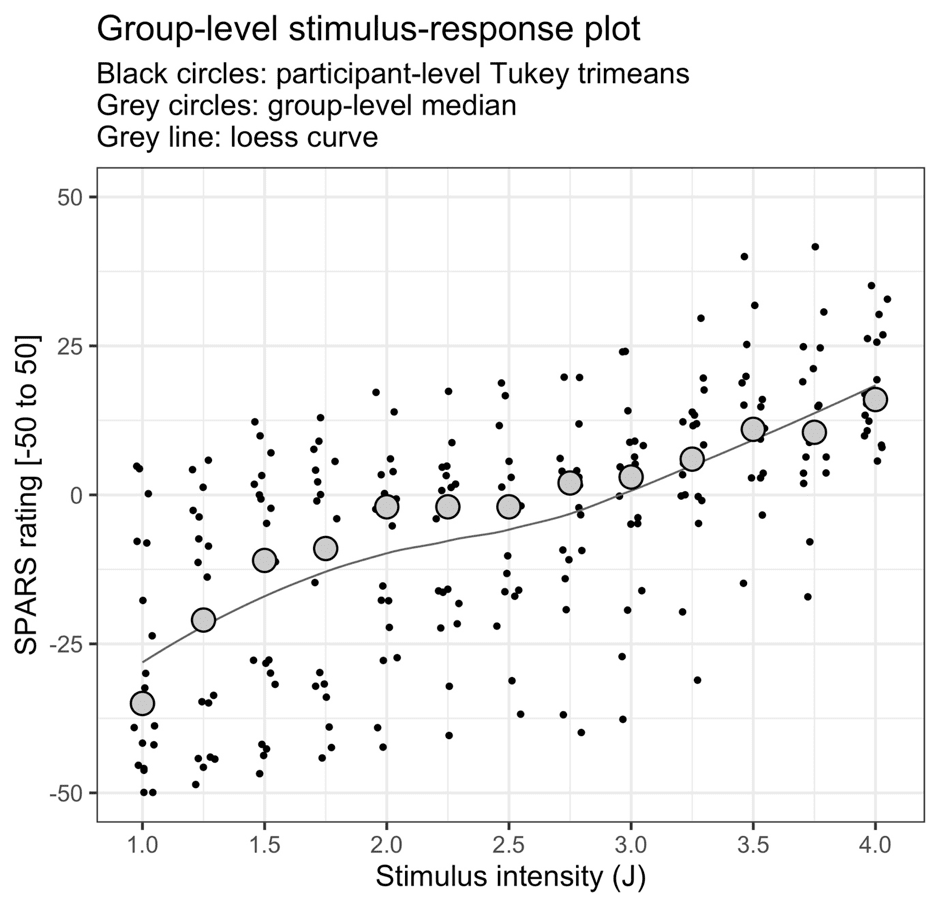

Here’s what we found: the relationship between stimulus intensity and SPARS rating was almost linear, with a slight curve (Figure 2) and it functioned about as well as an NRS does. Obviously, it captured a lot more information, particularly around pain threshold, than an NRS does.

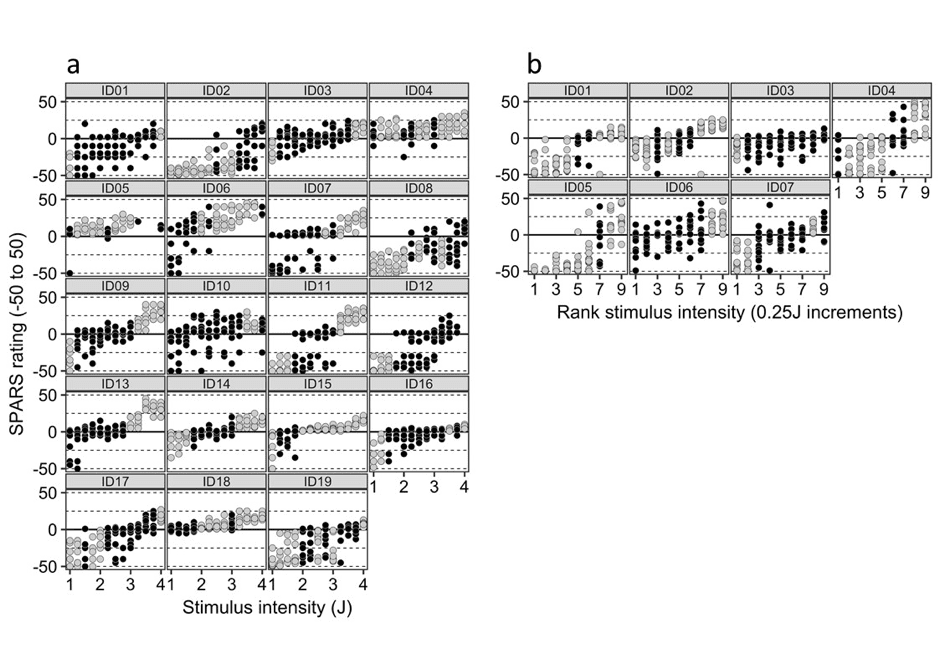

Take a look at the plot – see that slight change in shape of the curve over the pain threshold? That looked to us as though people were rating the same stimulus intensity as both ‘non-painful’ and ‘painful’ in different trials. We were surprised by how wide this apparent ‘zone of uncertainty’ might be, because ‘pain threshold’ is typically considered to be a reasonably thin virtual boundary between non-painful and painful events. Some of our previous work [e.g. 2, 3] and a whole heap of studies using pain threshold have been based on this assumption.

So we formally analysed this and as Figure 3 shows – the concept of a pain threshold as a clear boundary is very flimsy indeed!

I presented on the SPARS at the World Congress on Pain, where the scale attracted some interest from clinicians as well as scientists. As a clinician who has also been a patient, I can totally see that it might be useful to have the option to express that I no longer have pain, but what I feel isn’t yet ‘quite right’. It might give patients a way to report, for example, that bending their replaced knee joint is uncomfortable and approaches pain (perhaps a SPARS = -5), whereas straightening the knee is clearly painful (perhaps a SPARS = +15). Prompted by these considerations, we have asked a group of generous clinicians to explore what their patients think of the SPARS and to give us feedback. If you’d like to do the same, please feel free – you can find instructions and give us feedback here.

I like the SPARS because it gives people a chance to express more than only pain, and I think that can only improve communication and the quality of our research data. It holds up really well – as well as the 0-100 pain scales – so we can confidently use it. The next step is to replicate our findings with different stimuli and to work out if it is useful clinically.

Tory Madden

Tory is a physiotherapist who worked clinically before turning her focus toward research. She did her PhD with BiM, looking at classical conditioning and pain. She is now a postdoc at the University of Cape Town, where she is exploring the role of social threat and is also involved in teaching. Tory spends some of her spare time running in the mountains – a necessary pastime that conveniently balances her penchant for excessive consumption of chocolate and other tasty delights.

References

[1] Victoria J. Madden, Peter R. Kamerman, Valeria Bellan, Mark J. Catley, Leslie N. Russek, Danny Camfferman, G. Lorimer Moseley (2019) Was That Painful or Nonpainful? The Sensation and Pain Rating Scale Performs Well in the Experimental Context. J Pain 20(4); 472.e1–472.e12

[2] Victoria J. Madden, Valeria Bellan, Leslie N. Russek, Danny Camfferman, Johan W.S. Vlaeyen, G. Lorimer Moseley. (2016) Pain by Association? Experimental Modulation of Human Pain Thresholds Using Classical Conditioning. J Pain 17(10); 1105–1115

[3] 2019. Modulating pain thresholds through classical conditioning. PeerJ 7:e6486 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6486