A “walk in the park” is more difficult than it sounds for someone with Peripheral Arterial Disease. This condition, called Intermittent Claudication (IC), is caused by narrowing of the lower-limb arteries which reduces blood flow to the muscles during walking resulting in a cramping leg pain. People often have to slow or stop walking every few minutes to let the pain subside – such walking limitations reduce mood, and limit their daily activities and quality of life.

An effective, but underused, treatment for IC is regular walking exercise. There is robust, synthesized high-quality evidence from randomized controlled trials that exercise therapy can lead to improvements that are often clinically – and personally – significant, enabling at least 2-fold-gains in symptom-free walking[1]. Exercise therapy is therefore recommended as first-line treatment in the pathway of care for IC patients.

However, people with IC must undertake substantial changes to their current behaviour in order to start the program, and then adhere to a regimen of progressive exercise. Being advised to walk – when walking itself causes pain – is counterintuitive to many people. Perceptions about walking treatment may not fit with how people understand their IC, including its cause, severity, and their own ability to control symptoms. As a result, they may believe that walking is unhelpful or unnecessary. Other barriers that IC patients must overcome include the need to stop and rest their legs, challenges of walking on uneven pavement or uphill, and feeling like they are a burden when walking with others.[2,3]

We are interested in improving the health, function, and quality of life of people with IC by supporting self-management through regular walking exercise. To date, evidence suggests that home-based exercise programmes are less effective than centre-based programmes.[4] However, past home-based interventions have lacked a robust foundation in behaviour-change theory and techniques, which are essential to supporting uptake and adherence to walking.[5] In addition, few programmes have honed and maximized the expertise of physiotherapists in prescribing, delivering, and supervising exercise therapy remotely.

So how can we help people with IC to walk more?

We conducted a series of qualitative and quantitative studies to develop a novel, physiotherapist-led behaviour change intervention aimed at increasing walking in people with IC. We incorporated two established theories of health behaviour-change, the Theory of Planned Behaviour and the Common Sense Model of Illness Representations, to the design and interpretation of the studies.

We interviewed 19 people (aged 44-79 years) with IC. They expressed a desire for tailored prescriptions and clear walking guidelines, especially in terms of the appropriate exercise intensity and, crucially, how much pain or discomfort they should endure whilst walking, before taking a rest. This is in stark contrast to the often brief and generic advice received following a diagnosis of IC by a vascular specialist, which does not change behaviour[4]. In addition, these tailored messages should be framed around the impact of IC on the patient and engender realistic expectations of the potential outcomes of walking treatment.

Our systematic review identified 6 randomised trials reporting key behaviour-change strategies associated with increased walking in people with IC. These included support for people to identify and problem-solve barriers to walking, and to self-monitor and evaluate their performance against walking goals. We incorporated these strategies in our new programme.[5]

We invited 142 patients to complete questionnaires about their walking, illness, and treatment beliefs and to complete a 6-minute walk test. Participants performed better on the walk test if they had formed intentions to walk, felt they had control over their condition, believed that their treatment was efficacious, had a coherent understanding of their IC, and attributed the cause of IC as having modifiable risk factors.

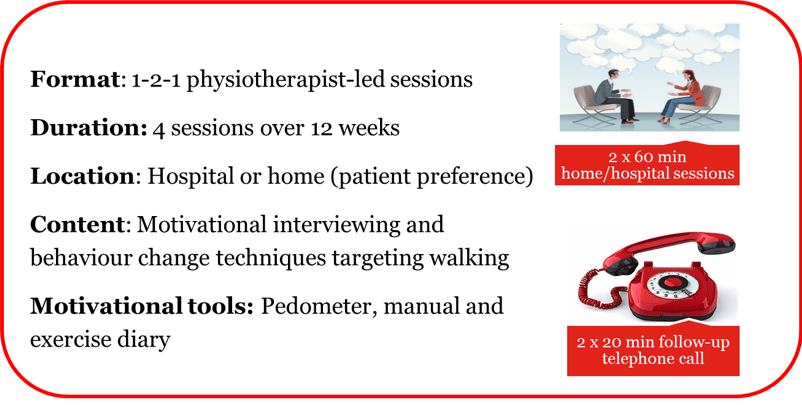

We used the information from these three studies to design our new treatment, which is called MOSAIC (MOtivating Structured Walking Activity in People with Intermittent Claudication). MOSAIC provides two 60-min face-to-face sessions and two 20-min telephone calls with a physiotherapist whom we had trained in motivational interviewing and behaviour-change techniques.

In a randomized controlled feasibility trial comparing MOSAIC to an attention-control[6], we found high study retention, adherence, and acceptability of the MOSAIC intervention. The 6-minute walk test was a robust measure, which was able to capture clinically relevant parameters such as both pain-free and maximum walking durations. The intervention was acceptable both to the patients and physiotherapist, who reported that home-based treatment was a convenient alternative which facilitated a collaborative relationship. Learning and recommendations to improve MOSAIC were taken on board, including suggestions to have more structured content and training prior to delivering booster telephone calls and the use of pedometers to support self-monitoring.

We are now conducting a multicentre randomised controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of MOSAIC for improving walking ability (measured by a 6-minute walk test) at 3 months follow-up. We are also interested in whether MOSAIC can improve activities of daily living and health-related quality of life, i.e., important targets of walking programmes for which the effects of walking remain unclear. We hope that MOSAIC will provide an alternative approach to prescribing and supervising exercise therapy as treatment for IC, and will add to the body of knowledge on incorporating psychological approaches into physiotherapy practice.

About the authors

Melissa N Galea Holmes, PhD is a Research & Implementation Facilitator at the NIHR CLAHRC North Thames, University College London, United Kingdom. Her research interests focus on improving care for patients with vascular disease, and the development and evaluation of interventions to improve exercise or physical functioning in people with long-term conditions. @MGaleaHolmes

Melissa N Galea Holmes, PhD is a Research & Implementation Facilitator at the NIHR CLAHRC North Thames, University College London, United Kingdom. Her research interests focus on improving care for patients with vascular disease, and the development and evaluation of interventions to improve exercise or physical functioning in people with long-term conditions. @MGaleaHolmes

John A Weinman is Professor of Psychology as applied to Medicines at the Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Emeritus Professor at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience in King’s College London. His research focuses on the influence of psychological processes on health, illness and health care delivery. He is particularly interested in the role of psychological factors in adaptation to and recovery from major illness and treatment, including surgery.

John A Weinman is Professor of Psychology as applied to Medicines at the Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Emeritus Professor at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience in King’s College London. His research focuses on the influence of psychological processes on health, illness and health care delivery. He is particularly interested in the role of psychological factors in adaptation to and recovery from major illness and treatment, including surgery.

Lindsay M Bearne is a physiotherapist and Senior Lecturer in the Department of Population Heath Sciences, King’s College London, United Kingdom. Her research interests include the impact of long-term musculoskeletal and vascular conditions on physical function and quality of life and the design, testing and implementation of exercise-based rehabilitation and self-management programmes. She is the Chief Investigator of the MOSAIC Trial.

Lindsay M Bearne is a physiotherapist and Senior Lecturer in the Department of Population Heath Sciences, King’s College London, United Kingdom. Her research interests include the impact of long-term musculoskeletal and vascular conditions on physical function and quality of life and the design, testing and implementation of exercise-based rehabilitation and self-management programmes. She is the Chief Investigator of the MOSAIC Trial.

References

[1] Lane R, Harwood A, Watson L, Leng GC. Exercise for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;12:Cd000990.

[2] Galea Holmes MN, Weinman JA, Bearne LM. ‘You can’t walk with cramp!’ A qualitative exploration of individuals’ beliefs and experiences of walking as treatment for intermittent claudication. J Health Psychol. 2015.

[3] Galea MN, Bray SR, Martin Ginis KA. Barriers and facilitators for walking in individuals with intermittent claudication. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2008;16(1):69-84.

[4] Hageman D, Fokkenrood HJ, Gommans LN, van den Houten MM, Teijink JA. Supervised exercise therapy versus home-based exercise therapy versus walking advice for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4:Cd005263.

[5] Galea M, Weinman J, White C, Bearne L. Do Behaviour-Change Techniques Contribute to the Effectiveness of Exercise Therapy in Patients with Intermittent Claudication? A Systematic Review. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 2013;46(1):132-141.

[6] Galea Holmes MN, Weinman JA, Bearne LM. A randomized controlled feasibility trial of a home-based walking behavior–change intervention for people with intermittent claudication. Journal of Vascular Nursing. 2019.