Most commonly used exercise therapies for back pain are aimed at having an effect on some mechanical or tissue based aspect of spinal function. From range of motion exercises to muscle balance, endurance or strengthening exercises the (not unreasonable) rationale is that back pain is associated with abnormal spinal function – address that with exercise and back pain should improve.

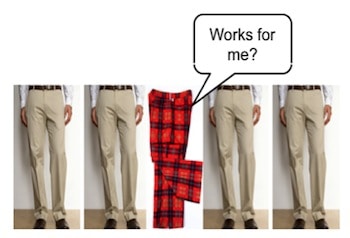

The problem is that, whichever way you slice the data, the effects of exercise are small to moderate at best (kind of the therapeutic equivalent of beige slacks, better than nothing but generally underwhelming). It doesn’t seem to matter what type of exercise you do, comparative trials of different types rarely demonstrate a difference and systematic reviews have not clearly demonstrated a type of exercise that is superior. Many argue that the problem is with the data not the treatments; the lack of targeting treatments to the group of patients for whom it is appropriate means that the true effect is washed out by all those people in the trial for whom the treatment was inappropriate or ineffective. But you all know this already and I am repeating myself.

A new review out of Switzerland, just published in the European Spine Journal has taken the issues of exercise therapy for CLBP and subgroups and looked at the data in a different way. If there are specific subgroups of patients for whom exercise regimes work the way that they were designed to, then any improvements seen in trials should be correlated with a change in an appropriate measure of spinal performance (for instance improved range of motion for ROM exercises, or improved spinal endurance or strength for those kind of regimens). So they sourced all rehab trials that incorporated exercise and a measure of spinal function and reported the results of correlation analyses between clinical outcomes (pain and disability) and physical function.

Their results are fascinating. The overwhelming majority of those trials that looked found no correlation between clinical outcome and spinal functional performance, and the few that did found weak or inconsistent correlations. So when people with CLBP feel better after exercise therapy, that change does not seem to be reliably reflected in improvements their spinal function.

It could be agued that the researchers in these trials just measured the wrong parameter of spinal function. I wonder what the correct measure would be? Also these studies might not have adequate power to detect a correlation, particularly if the subgroup of responders is small, but that in itself would be a fairly powerful indication of the limitations of the therapy.

How should this be interpreted? Directly it infers that where exercises help it’s not by the traditional mechanisms by which we thought they might. It lumps the effects of exercises, at least for now, under the label “non-specific”. Indirectly it suggests that if there are specific subgroups for whom exercise therapies have benefits, then the improvement in those subgroups was not likely due to the suggested “active ingredient” of the exercises given. I think it pulls the rug out a bit further from under the feet of the subgroup argument because in terms of specific effects there seem to be no funky britches hiding in the sea of boring beige.

About Neil

As well as writing for Body in Mind, Neil O’Connell is a researcher in the Centre for Research in Rehabilitation, Brunel University, West London, UK. He divides his time between research and training new physiotherapists and previously worked extensively as a musculoskeletal physiotherapist. He also tweets! @NeilOConnell

As well as writing for Body in Mind, Neil O’Connell is a researcher in the Centre for Research in Rehabilitation, Brunel University, West London, UK. He divides his time between research and training new physiotherapists and previously worked extensively as a musculoskeletal physiotherapist. He also tweets! @NeilOConnell

He is currently fighting his way through a PhD investigating chronic low back pain and cortically directed treatment approaches. He is particularly interested in low back pain, pain generally and the rigorous testing of treatments. Link to Neil’s published research here. Downloadable PDFs here.

Reference

Steiger F, Wirth B, de Bruin ED, & Mannion AF (2011). Is a positive clinical outcome after exercise therapy for chronic non-specific low back pain contingent upon a corresponding improvement in the targeted aspect(s) of performance? A systematic review. Eur Spine J PMID: 22072093 [Epub ahead of print]