Over this holiday season we are publishing our Editor’s picks of 2018 for you to read and enjoy again. The second one is by Kai Karos.

—

Times are changing. Our understanding of pain from a purely biomedical perspective has evolved to a biopsychosocial perspective of pain. Intuitively, pain has long been recognized as an experience that can fundamentally threaten our need to feel safe, both physically and psychologically. But what does it mean to say that pain is social? In earlier blog posts we have highlighted some of the ways in which social context can powerfully change how pain is experienced (here and here). In fact, recent proposals to change the very definition of pain have emphasized that pain is an experience associated with sensory, emotional, cognitive, and social components [8]. However, while this new definition would better reflect the underlying biopsychosocial vision of pain, it is still unclear what is meant by describing pain in social terms.

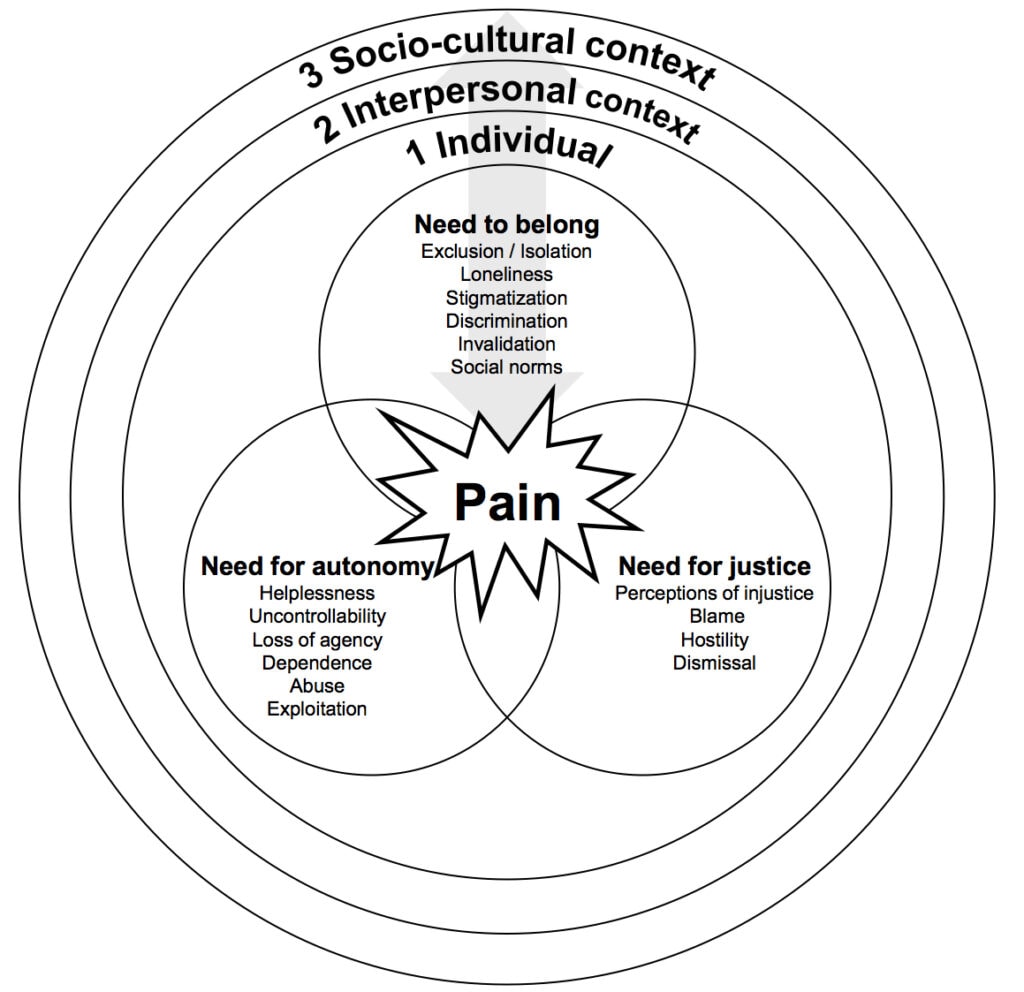

There is growing evidence and recognition that the experience of acute and chronic pain is associated with a burden to the social life of the person in pain [4]. Here, we want to go one step further and propose that the experience of pain is intrinsically social, because it threatens some of our most fundamental interpersonal needs, in the same way that it threatens the need for physical and psychological safety (see Figure 1).

First, we have a fundamental need for autonomy and control. We appreciate the feeling of control over our actions, a sense of having fate in our own hands. This sense of control is central to our own survival, because it allows us to predict the environment and avoid unpleasant experiences, such as pain. However, especially now, the experience of pain in particular and illness in general, threatens this need in several ways. Pain itself might be uncontrollable (e.g., we are not always able to predict or prevent pain, especially when it is chronic) but more crucially, we often find ourselves in situations where we are not able to deal with pain on our own. We have to rely on others (e.g., family, friends, health-care providers) for help in managing, alleviating, explaining, and making sense of pain. In this sense, pain makes us vulnerable because it can make us dependent on others and their evaluation. It is therefore no surprise that feelings of helplessness, shame, guilt, and uncontrollability are common in people with pain. This becomes especially clear in cases of victimization (e.g., bullying or torture), where pain is intentionally inflicted by others [7].

Second, humans are social animals, and they have a fundamental need for significant social relationships. Pain, especially when chronic, can make it harder to maintain social relationships (e.g., pain might prevent someone from engaging in valued hobbies with others). Beyond that, people with pain are frequently stigmatized and excluded by others, especially when there is no underlying medical pathology [5]. Pain reports are still often not taken seriously by others and people with pain often feel misunderstood or disbelieved by others, leading to feelings of social isolation. Chronic pain in particular is in direct conflict with how our society has come to view pain: A short-lived and fixable problem that sometimes interferes with an otherwise healthy, functional and productive member of society.

Third, pain threatens our need to believe that life is fair and just. Experiences of injustice are common in people with pain. No one “deserves” his or her pain and yet we have a tendency to hold someone or something responsible when something bad happens to us. People in pain are not always treated fairly. They are disbelieved, excluded, undertreated, and confronted with allegations of deception, sometimes based on personal characteristics such as ethnicity, race, sex, or age [1,2,6].

Why does all of this matter? It matters because threatening interpersonal needs comes with consequences. A state of helplessness, social isolation and being treated unfairly negatively affects our physical and mental health, and it negatively affects pain too. Across the board, when pain threatens these fundamental social needs, it has been shown to make the experience of pain worse. With this realization comes greater responsibility but also opportunity: If we truly appreciate the biopsychosocial model of pain, we need to understand, investigate and acknowledge that pain can also have dire costs in the social sphere, and that these costs deserve attention, both in research as well as in the clinic. At the same time, addressing and managing threats to the social self, can also directly impact the experience of pain itself.

Pain is social, thus managing the social context of pain is managing pain.

For a full account, see our recent topical review in PAIN [3]

About Kai Karos

Kai Karos finished his bachelor and research master degree at Maastricht University, the Netherlands. He is currently a doctoral researcher in the Research Group on Health Psychology at the University of Leuven (Belgium) under the supervision of Johan Vlaeyen, Ann Meulders and Liesbet Goubert. His PhD research concerns the effects of a threatening social context on pain perception and pain expression. These processes are mainly investigated using experimental laboratory research with healthy participants. For more information see here.

Kai Karos finished his bachelor and research master degree at Maastricht University, the Netherlands. He is currently a doctoral researcher in the Research Group on Health Psychology at the University of Leuven (Belgium) under the supervision of Johan Vlaeyen, Ann Meulders and Liesbet Goubert. His PhD research concerns the effects of a threatening social context on pain perception and pain expression. These processes are mainly investigated using experimental laboratory research with healthy participants. For more information see here.

References

[1] Anderson KO, Green CR, Payne R. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Pain: Causes and Consequences of Unequal Care. J. Pain 2009;10:1187–1204. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2009.10.002.

[2] Craig KD. The social communication model of pain. Can. Psychol. Can. 2009;50:22–32. doi:10.1037/a0014772.

[3] Karos K, Williams AC de C, Meulders A, Vlaeyen JWS. Pain as a threat to the social self. Pain 2018;00:1. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001257.

[4] Piotrowski C. Chronic pain patients and loneliness: A systematic review of the literature. Loneliness in life: Education, business, society. NY: McGraw Hill, 2014.

[5] De Ruddere L, Craig KD. Understanding stigma and chronic pain. Pain 2016;157:1. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000512.

[6] Seers T, Derry S, Seers K, Moore RA. Professionals underestimate patients’ pain. Pain 2018;159:1. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001165.

[7] Voerman JS, Vogel I, De Waart F, Westendorp T, Timman R, Busschbach JJ V, Van De Looij-Jansen P, De Klerk C. Bullying, abuse and family conflict as risk factors for chronic pain among Dutch adolescents. Eur. J. Pain (United Kingdom) 2015;19:1544–1551.

[8] Williams ACDC, Craig KD. Updating the definition of pain. Pain 2016;157:2420–2423. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000613.