“I can’t really understand ‘em”

(Middle aged Aboriginal man with chronic low back pain)

Have you ever heard someone say this or words of similar effect after they have seen a health practitioner such as a doctor, surgeon, physiotherapist or chiropractor for treatment for low back pain? Have you ever experienced this feeling yourself as a patient?

For people with chronic low back pain (CLBP) the chance to tell their story and express concerns to a health practitioner is important. Many patients would like to receive an explanation about their pain in understandable terms with reassurance, support and advice. Successful communication provides the foundation for positive patient / health practitioner interactions. Evidence based care relies on successful communication; outcomes are better, patients are more satisfied with care, there is greater trust and a stronger therapeutic relationship and patients’ behaviours are more concordant with recommended care. Conversely problems during health care consultations commonly occur when there is a breakdown in communication.

Communication with health practitioners was an issue that emerged in a qualitative study we undertook that explored the experiences of Aboriginal Australians with CLBP (1). Our study involved a qualitative, culturally secure research approach using in-depth ‘yarning’ to explore the experiences of 32 Aboriginal Australians with CLBP who live in rural/remote Australia (we’ve written previously about it here). Communication was the most important issue raised by participants as they talked about their experiences of health care.

Our findings highlighted aspects of the content and the style of communication that were important.

Participants were often dissatisfied when the content of information communicated to them was not evidence based or contradicted their personal experiences. An example of this was given by a woman who had been advised by her doctor to lose weight to manage her CLBP:

“They wanted me to lose weight. I lost the weight and it (the pain) was still the same so I put the weight back on”.

Other examples related to radiological imaging findings:

“I just seem to sit listening to the same story… It’s the wear and tear of your bones”.

The use of medical jargon was another significant issue raised:

“I’m not sure, what they, he did… it was all big terminologies”.

Conversely a style of communication that was a two-way conversation, and health practitioners who applied good listening skills were positively regarded: “[I like the doctor to] take time to look at you, listen to you”. This finding is perhaps not unexpected however a number of participants described a positive communication experience as involving a ‘yarn’ with their doctor; alluding to an informal conversational style during the consultation that involved sharing of information and stories between both parties. “Taking the time” to yarn was also regarded positively.

Caution must be exercised in interpreting research findings from rural/remote Aboriginal Australia to other contexts, however we feel our study raised issues with wider relevance.

Firstly, it is important for health practitioners to have up-to-date knowledge about CLBP in order to communicate successfully with patients. Whilst this seems straightforward, practitioners knowing and then applying the evidence is a tremendous challenge; there a well-recognised gap between evidence and practice and the burden of CLBP could be reduced if practitioners would simply apply current available evidence (2).

Secondly, practitioners need to convey evidence based information in a style that is suitable to the context of their patient and their preferences for communication. A ‘yarning’ style may not suit all patients however many elements of a ‘yarning’ style, such as consultations that involve a two way exchange of information, an informal conversational style, and a storytelling/narrative might have universal appeal to people with a complex and multifactorial condition such as CLBP (and are arguably lacking in many health care encounters).

Finally, and most importantly, our study reminds us of the primacy of good communication from the perspective of patients. Evidence based care involves high quality communication that is adaptable to the context of the patient. Our challenge is to recognise and provide this to our patients in a person centred manner.

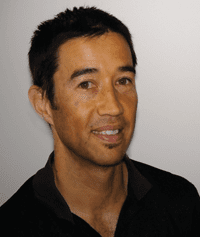

About Ivan Lin

Ivan Lin is spending a year traveling parts of the southern hemisphere with his young family. When he returns to his real life he is a researcher with the Western Australian Centre for Rural Health and physiotherapist with the Geraldton Regional Aboriginal Medical Service (more details are here). He is fortunate to collaborate with researchers in the areas of musculoskeletal pain, Aboriginal health, public health and anthropology and this blog is based on collaboration with Professors’ Peter O’Sullivan, Juli Coffin, Leon Straker, Donna Mak and Sandy Toussaint. He is lucky enough to live on Yamajti country in a town known for its sun, wind, surf and crayfish, more than 400km/250 miles from a major city.

Ivan Lin is spending a year traveling parts of the southern hemisphere with his young family. When he returns to his real life he is a researcher with the Western Australian Centre for Rural Health and physiotherapist with the Geraldton Regional Aboriginal Medical Service (more details are here). He is fortunate to collaborate with researchers in the areas of musculoskeletal pain, Aboriginal health, public health and anthropology and this blog is based on collaboration with Professors’ Peter O’Sullivan, Juli Coffin, Leon Straker, Donna Mak and Sandy Toussaint. He is lucky enough to live on Yamajti country in a town known for its sun, wind, surf and crayfish, more than 400km/250 miles from a major city.

References

[1] Lin I, O’Sullivan P, Coffin J, Mak DB, Toussaint S, & Straker L (2014). ‘I can sit and talk to her’: Aboriginal people, chronic low back pain and healthcare practitioner communication. Aust Fam Physician, 43 (5), 320-4 PMID: 24791777

[2] Williams CMM, Maher CGP, Hancock MJP, McAuley JHP, McLachlan AJP, Britt HP, et al (2010). Low Back Pain and Best Practice Care Arch Intern Med. 170 (3):271-7 DOI: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.507