Some people with persistent pain have altered perceptions of parts of their body. For example they can perceive their affected limbs as having some distortions of size, perhaps with enlarged hands or very thin forearms. They can also feel that the limb is in a different position to its actual location and that areas of body or limb segments are much colder or hotter than they really are. They know these perceptions are not true, because of course, they can see they are not, but nevertheless the feeling of these alterations in their body remain and can be distressing. It can be difficult for people to communicate their perceptions about their body to clinicians and there is a worry that they won’t be believed or will be seen as deluded or mad.

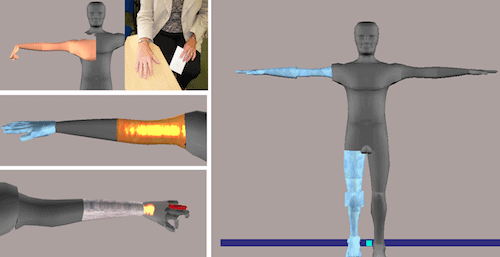

Members of the Pain Research group and Centre for Appearance Research at my university, the University of the West of England (UWE), in Bristol, UK, have been working with a digital media computer scientist, also at UWE, to develop a tool that patients can use to communicate alterations in their body perception to clinicians or to others. The tool gives users an on-screen image of a 3D human figure which can be manipulated to give an impression of their body perception. They can resize and reposition any body parts that they feel are different and apply textures to represent hot or cold sensations, hard ‘stone like’ feelings, or the feeling of body parts being insubstantial.

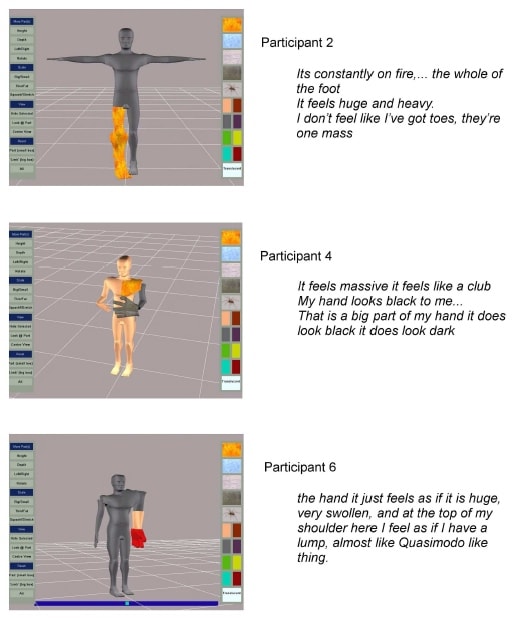

We tested the prototype with patients who were attending a Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) rehabilitation programme at the Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases in Bath. Altered body perception is a common feature of CRPS. Ten people tried the first version in a consultation with a research nurse. They produced some remarkable representations; some examples are shown here[1].

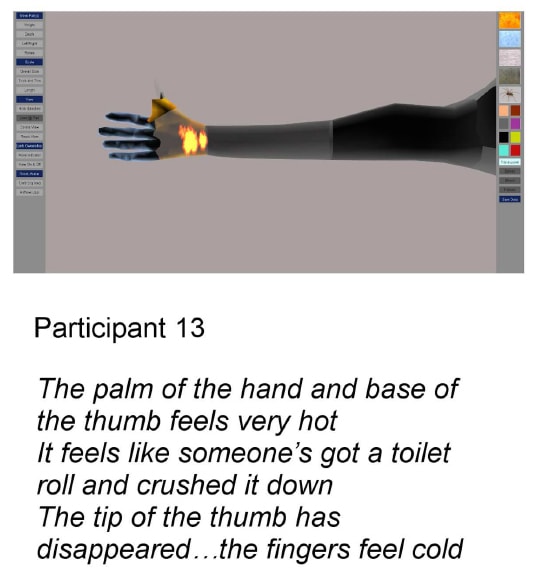

All ten participants thought the tool was useful for communicating their body perceptions and much better than the sketches used in the standard assessment process. They liked the ability to rescale the limbs and the application of textures, particularly the fire effect which they used to represent burning pain. On the whole they liked the neutrality of the avatar too. There were some aspects identified for improvement: people wanted the facility to provide more detailed representation of the hands and also expressed a wish to be able to represent conflicting sensations. For example extreme burning was sometimes experienced with cold sensation in the affected region. Changes were made to meet these requirements and mark II of the tool was tested with three further patients who used the new features and liked them. An example is shown here[2].

This initial testing has been reported in a methods article in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience [3].

Since then we’ve explored the use of the tool with eleven stroke survivors who attended local stroke support groups. Ten of them changed the avatar to illustrate alterations in body perception. A few of their pictures showed scaling changes, and one person illustrated a perception of altered position, but more typically the participants’ body representations described affected limb parts being very cold, stone like, or having shooting pains (see figure for examples). The stroke survivors welcomed the opportunity to express these sensations but were rather bemused that they hadn’t been asked about their body perception when they were in hospital.

Altered body perception is thought to result from changes that occur in the brain because it is not receiving the information it would normally get from moving limbs and feeling things in everyday living. Conditions like stroke and CRPS affect the ability to move and to receive sensory information about affected body parts. With further development we think the body perception tool has great potential for use with other conditions with sensorimotor consequences, but there might also be other applications. We are also investigating its potential for measuring change in body perception. If we can use it to reliably measure change then it is possible it could be a useful predictor for neuropathic pain or as an explanatory process measure in interventions for reducing persistent pain. I’d be interested to hear your ideas about its application.

About Ailie

Ailie Turton is an Occupational Therapist with over 25 years’ experience of Stroke Rehabilitation Research. She is a Senior Lecturer at the University of the West of England, Bristol, UK, and is a member of the Pain Research Group headed by Professor Candy McCabe. Through her research experience in stroke Ailie has developed interest in sensorimotor integration, spatial attention and neuroplasticity for recovery. These all have a bearing on body perception and there are parallels in the consequences of sensory and motor disruption between stroke and CRPS. Ailie has published work on both conditions.

Ailie Turton is an Occupational Therapist with over 25 years’ experience of Stroke Rehabilitation Research. She is a Senior Lecturer at the University of the West of England, Bristol, UK, and is a member of the Pain Research Group headed by Professor Candy McCabe. Through her research experience in stroke Ailie has developed interest in sensorimotor integration, spatial attention and neuroplasticity for recovery. These all have a bearing on body perception and there are parallels in the consequences of sensory and motor disruption between stroke and CRPS. Ailie has published work on both conditions.

Reference

[1] Figure 3, from Turton, Palmer, Grieve, Moss, Lewis and McCabe, Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 2013

[2] Figure 4, from Turton, Palmer, Grieve, Moss, Lewis and McCabe, Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 2013

Turton, A., Palmer, M., Grieve, S., Moss, T., Lewis, J., & McCabe, C. (2013). Evaluation of a Prototype Tool for Communicating Body Perception Disturbances in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7 DOI: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00517