A middle aged patient with slow onset shoulder pain was concerned about the results of a left shoulder ultrasound that showed a partial tear in her rotator cuff. Since the result she had taken to wearing a sling to protect the shoulder from “further tearing”.

A patient with a three year history of work related, disabling low back pain, and a history of depression, worse since she was fired, was seeing a physiotherapist who was applying therapeutic ultrasound to her left sacroiliac joint.

An acquaintance in the community said the surgeon he had seen for his sore right hip told him that they “were destined to meet” because of the degeneration in his hip. The man had not had hip pain previously and had done no rehabilitation. Three weeks later he underwent a total hip replacement.

Even without knowing the full clinical history of these diverse real-life cases, there are questions about whether their health care management was of high quality. I’m sure many BiM readers can recount examples where they have seen or heard of questionable health care practices. Unfortunately research supports this. Unfortunately we, and by ‘we’ I refer to a collective ‘we’ of clinicians such as doctors, physiotherapists, chiropractors, osteopaths and others who work with patients with musculoskeletal pain, don’t always practice in a way that is consistent with research evidence. Over-use of imaging[1], the prescription ‘opioid epidemic’[2], increases in unproven surgeries[3], and a failure to provide patients with self-management advice[4] are just some of the problems. Admittedly sometimes this might be justifiable (a fully informed client may voluntarily choose treatments that are unsupported by research evidence I suppose) but in other instances this results in iatrogenic disability and excessive costs to people and society. It’s a crazy paradox that for conditions associated with such a tremendous burden that we don’t manage them all that well. We need to change the way musculoskeletal pain is managed.

Our study was a step in working toward this change[5]. We were interested in whether, across musculoskeletal pain conditions, we could identify a common set of recommendations to manage musculoskeletal pain. We thought that if we could, it would provide consumers, clinicians, educators and health decision makers with a simple way of knowing what higher quality musculoskeletal pain care looked like.

A common set of recommendations could be used in multiple ways. Consumers with MSK pain could be informed about what to expect when they sought care for a musculoskeletal pain complaint. Clinicians could assess their practice and identify gaps. Educators could use them as a framework for teaching about musculoskeletal pain. Health decision makers could assess the quality of care and in so doing, identify areas of concern.

We first undertook a systematic review of contemporary musculoskeletal pain clinical practice guidelines. Clinical practice guidelines are an important resource for clinicians. They are intended to optimise patient care and include recommendations for management. They are developed via a systematic appraisal of research evidence and careful assessment of the benefits and harms of each management option. Clinical practice guidelines should be developed in a way that is transparent and rigorous.

Unfortunately our first finding was that not all musculoskeletal pain clinical practice guidelines were rigorously developed or reported. In our first systematic review we only ranked only 8 of 32 clinical practice guidelines as high quality[6] (see our article for how we determined this). The lesson – be cautiously critical of musculoskeletal pain clinical practice guidelines.

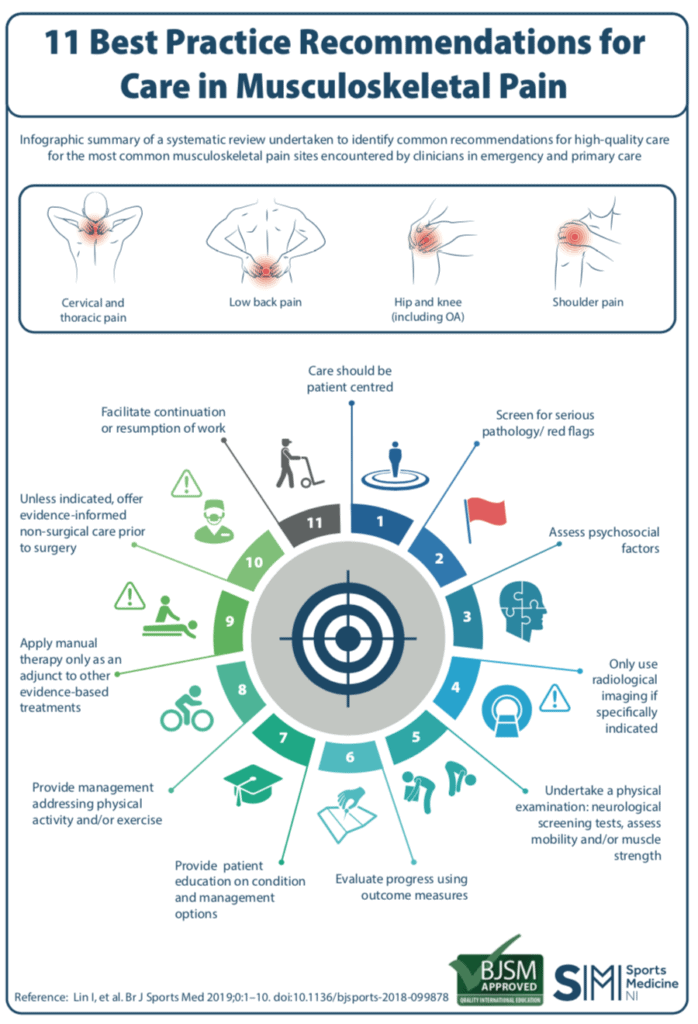

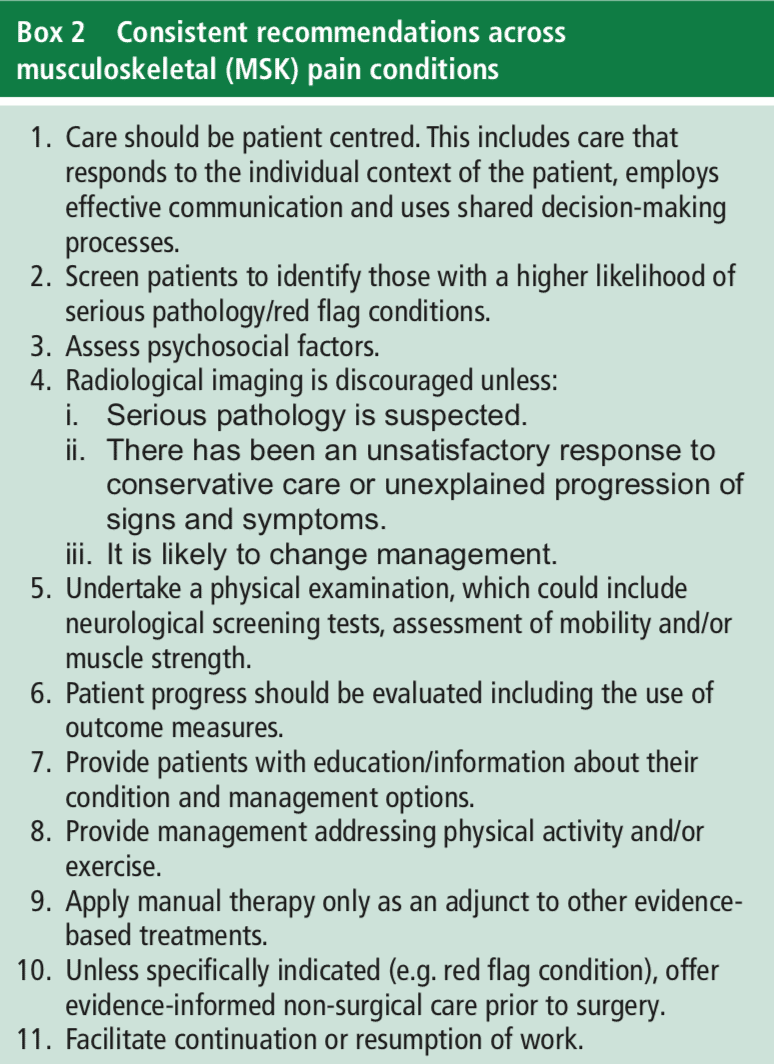

Following an updated search we ranked 11 clinical practice guidelines as high quality. From these we identified 11 common recommendations for the care of musculoskeletal pain conditions (included from our article below).

We also identified treatments for certain conditions that should not be provided. For example, patients with low back pain should not be prescribed opioid-based medications or Panadol alone, given rocker shoes or orthotics, receive disc replacement surgery, or injections into the back when there was no leg pain associated with back pain. Patients with osteoarthritis should be wary of having arthroscopic knee surgery.

Many clinicians will not find these recommendations new. The value of our study is to synthesise recommendations from high quality clinical practice guidelines, across multiple musculoskeletal pain complaints, in a way that can be readily used and applied. One (non-validated, non-rigorous) indicator that these recommendations are useful to clinicians is the speed at which infographics based on the article have appeared. Inside a week infographics in English and Portuguese have surfaced online to use as simple communication tools (see below – with a shout out to Dr Alan Rankin for what must be a record for the fastest development of an unsolicited infographic).

It is important to note that we excluded musculoskeletal pain problems with identified pathologies such as fractures or inflammatory arthropathies such as rheumatoid arthritis. Even though there were only clinical guidelines for spinal pain (low back and neck), knee/hip osteoarthritis, and the shoulder (rotator cuff), we believe the recommendations could apply to a wider range of non-traumatic musculoskeletal pain conditions. There were also areas not included within current clinical practice guidelines that are important to managing musculoskeletal pain, but we could not include in our synthesis. Examples were the assessment of lifestyle factors such a smoking, poor sleep and overweight/obesity, and treatments that target psychosocial factors. These factors may work their way into clinical practice guidelines in the future.

So please take the recommendations, critique them, send us some (constructive) feedback – good or bad, and if helpful, put them to use.

About Ivan Lin

Ivan Lin is a clinician/researcher who lives and works in rural coastal Western Australia on Southern Yamaji Country. His main interest is improving the quality of musculoskeletal pain care, including the effectiveness of care and clinical communication. He predominantly works in Aboriginal health care. He is also interested in other things that contribute to health and wellbeing in communities, including social determinants, enhancing physical activity, education, and health care delivery. Apart from when he can contribute to improving these things he is also inspired by working with good people. The good people and team members on this project were Louise Wiles, Rob Waller, Peter O’Sullivan, Roger Goucke, Yusuf Nagree, Leon Straker, Chris Maher, and Mick Gibberd.

References

[1] Jenkins HJ, Downie AS, Maher CG, et al. Imaging for low back pain: is clinical use consistent with guidelines? A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Spine Journal

[2] Sullivan MD, Howe CQ. Opioid therapy for chronic pain in the United States: Promises and perils. Pain 2013;154:S94-S100.

[3] Judge A, Murphy RJ, Maxwell R, et al. Temporal trends and geographical variation in the use of subacromial decompression and rotator cuff repair of the shoulder in England. The bone & joint journal 2014;96-B(1):70.

[4] Williams CMM, Maher CGP, Hancock MJP, et al. Low Back Pain and Best Practice Care: A Survey of General Practice Physicians. Arch Intern Med 2010;170(3):271-77.

[5] Lin I, Wiles L, Waller R, et al. What does best practice care for musculoskeletal pain look like? Eleven consistent recommendations from high-quality clinical practice guidelines: systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2019:bjsports-2018-099878.

[6] Lin I, Wiles LK, Waller R, et al. Poor overall quality of clinical practice guidelines for musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2017;52(5):337-43.