How many people have sustained an injury (accidental or other) after a few too many drinks, to find that the pain only really kicks in after they have sobered up? Pain experienced the morning after our drunken exploits may lend weight to the established belief that alcohol provides an effective form of pain relief. Historically, alcohol was a predecessor to modern anaesthetics. It wasn’t quite as long ago as we might imagine that patients were carried into operating theatres in a drunken stupor to undergo surgery. Melzack and Wall recount grisly historical tales of strong men immobilising terrified patients while surgeons amputated a leg or drilled a hole in the skull, often with incredible speed.

Given that the analgesic effects of alcohol appear to be well supported anecdotally, we thought it would be interesting to review the research evidence. We looked at the results of controlled experimental studies assessing the effect of measured dosages of alcohol on experimentally-induced pain. The aim was to establish whether alcohol does result in pain relief and, if so, to quantify the magnitude of this effect.

Given the general level of interest in this area, there were fewer studies than we expected. A systematic search found 18 eligible experimental studies, involving a combined total of 404 healthy participants. All those taking part were exposed to painful experimental stimulation after being allocated to an alcohol or a no-alcohol control condition. Participants were 26 years old on average and were mostly male. Pain was assessed in a variety of ways, including pain ratings (0-10) and pain threshold (the point at which pain is first experienced). Studies were generally of good methodological quality; many reported randomisation of participants to conditions, precise measurements of blood alcohol and use of placebo groups who were given negligible levels of alcohol to reproduce its taste and smell.

A meta-analysis of the data from these studies provided robust support for the painkilling effects of alcohol. A mean blood alcohol content (BAC) of approximately 0.08% (around two pints of lager/medium glasses of wine) produced a small elevation of pain threshold and a moderate-to-large reduction in pain ratings. For pain ratings, pain was rated at around 5/10 in the control condition, which was reduced by around 25% after administration of alcohol. A dose-response relationship was also observed, with increasing levels of alcohol resulting in increasing analgesia (with alcohol dosages ranging from the equivalent of around half a pint of lager to three pints). Full results are published in the Journal of Pain.

Overall, these results suggest that alcohol does deliver effective relief from pain – at least for the type of relatively short-term pain induced in the laboratory. While there is uncertainty regarding the precise mechanism(s) underpinning the pain relieving effects of alcohol, suggested mechanisms include both indirect (e.g. through the reduction of anxiety) and direct effects (e.g. via the blocking of NMDA receptors in the central nervous system).

It is difficult to know how well these results generalize to acute pain outside of the laboratory. It is nevertheless interesting to note that pain intensity ratings of 5/10 can represent the threshold at which pain can have a serious impact on normal functioning. It is also hard to know whether the same level of analgesia observed for experimental pain extends to chronic pain complaints (e.g. back pain), as these two types of pain differ in their emotional, cognitive and physical components. Nevertheless, if alcohol blunts pain partly through reducing anxiety and other negative mood states, as has been suggested, it could be speculated that alcohol may be an especially effective analgesic for clinical pain states where levels of emotional distress are often high.

One implication of these findings is that the painkilling properties of alcohol could contribute to the increased usage of alcohol observed in patients with persistent pain. Furthermore, the accessibility and relative inexpensiveness of alcohol is likely to encourage its use as an analgesic in preference to more difficult-to-obtain drugs or interventions. Of course, excessive alcohol consumption can present substantial threats to long-term health and provides an increased risk for developing future chronic pain conditions. Furthermore, these findings suggest that the level of alcohol consumption needed to provide sustained moderate-to-large analgesia for persistent pain exceeds most countries’ guidelines for safe drinking. As such, efforts to promote awareness of alternative pain management strategies (e.g. physical therapy, exercise, controlled use of pain medication) with fewer long-term health consequences to vulnerable people is likely to be beneficial.

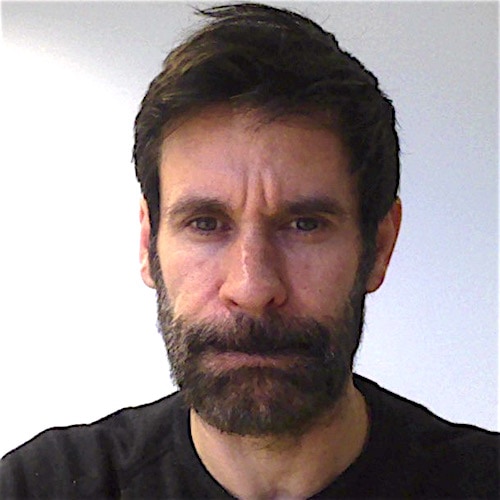

About Trevor Thompson

Trevor Thompson is a senior lecturer in the Psychology department at the University of Greenwich, UK. He has previously worked as a consultant statistician in the area of patient-reported outcomes in the US. He enjoys research examining the neurophysiological foundations of pain and exploring the potential for technology in pain management. But hates mime artists.

Trevor Thompson is a senior lecturer in the Psychology department at the University of Greenwich, UK. He has previously worked as a consultant statistician in the area of patient-reported outcomes in the US. He enjoys research examining the neurophysiological foundations of pain and exploring the potential for technology in pain management. But hates mime artists.

Reference

Thompson T, Oram C, Correll CU, Tsermentseli S, Stubbs B (2016) Analgesic Effects of Alcohol: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Experimental Studies in Healthy Participants. J Pain. 2016 Dec 2. pii: S1526-5900(16)30334-0.