Having written a number of posts on acupuncture (see here, here, and here) I guess my particular biases are reasonably apparent. So imagine my surprise when a large RCT published in the journal “Pain” reports a significant and substantial effect of Chinese acupuncture in comparison with sham acupuncture or conventional orthopaedic therapy for chronic shoulder pain. First glance demonstrates a well performed trial that boasts power and rigour. It is randomised, allocation is concealed, the outcome measures are appropriate, the data analysis appears sound. Time for a reappraisal?

Perhaps, but this finding is at odds with the recent big trials of acupuncture for pain which consistently show little to no difference between real acupuncture and sham acupuncture, regardless of the type of sham used (see links in the previous posts).

Reading more closely it is always interesting to check how the authors got around the problematic issue of devising a reasonable sham. This study, like many recent others used shallow but penetrating needles at non-acupuncture points [points that are not considered to be beneficial in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM).] In terms of assessing the value of odd theories like meridians this is not unreasonable but it does leave the authors with some interpretive challenges. For example if you don’t find a difference between active and sham do you conclude against acupuncture, or just conclude that acupuncture (or rather needle penetration) works, but not due to the folklore of TCM. Such interpretations are popular these days, but controversial.

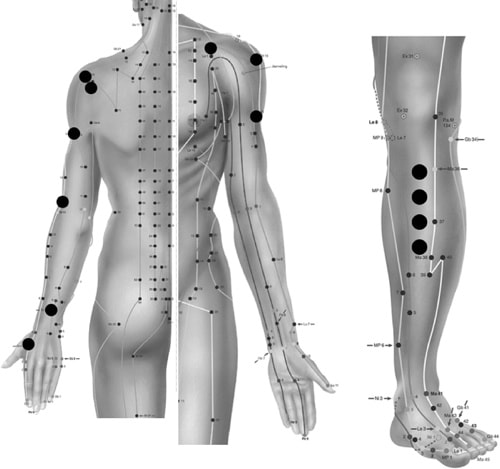

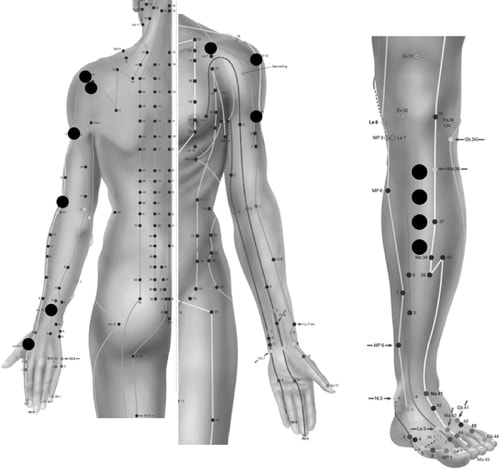

Still, there was a clear change between real and sham acupuncture in this study so that particular problem does not apply. So what could be going on? Here is a figure showing the location of the acupuncture points used in both groups.

Does anything particular jump out at you? If not, take a closer look. For real acupuncture (for shoulder pain, remember) the needles are spread around the shoulder and upper arm. In the sham group they are placed in the lower leg. Now put yourself in the patient’s position. If you are suffering with chronic shoulder pain which treatment would seem more credible to you? Treatment credibility is at the heart of the placebo effect and I think this represents a real issue. Unfortunately participants’ perceptions of treatment credibility were not measured (they often are these days) so we can’t quantify their effects in this study.

Now consider that the needles were inserted twice to four times as deep in the real acupuncture group, and twiddled by the acupuncturist throughout the treatment to elicit sensation (but not twiddled in the sham group) and it strikes me that you might have a much more convincing piece of therapeutic theatre. Then add the problem that it is clearly not possible to blind the therapists using this design and we can see that the real acupuncture group had a number of paths towards a bigger treatment effect that have nothing to do with the theories of Chinese Medicine.

There is the argument that the lasting improvements seen (after 3 months) and the improvement over conventional therapy add weight to the authors’ conclusions. But a convincing placebo might be enough to put patients on a path to lasting improvement and with most patients having had their pain for an average of around 10 months it is likely that many might have already tried and failed with conventional therapy, introducing a nocebo effect in this group. Participants in this study were acupuncture naïve, making this a novel therapy, and would have been signing up to take part for the chance of receiving acupuncture. We know that the kind of folk who volunteer for acupuncture trials seem to have generally high expectations of acupuncture to drive that placebo response. Unfortunately expectations were not measured but together these factors might add up to a heady brew and accentuate the differences between the groups.

Ultimately sham controls, if not indistinguishable (which would be the ideal) need to at least be as convincing as the real treatment. It is fair to acknowledge that these results could possibly be a reflection of the superiority of Chinese acupuncture over sham needling. Since the credibility of the sham, the integrity of patient blinding and the expectations of the participants were not measured we can’t say much for sure. But given the bulk of the existing evidence, the low probability that a pre-medieval argument from authority (the “ancient wisdom” plea) is actually correct and the issues discussed here it would seem more likely to me that a different interpretation might be at hand.

About Neil

Neil O’Connell is a researcher in the Centre for Research in Rehabilitation, Brunel University, West London, UK. He divides his time between research and training new physiotherapists and previously worked extensively as a musculoskeletal physiotherapist. He also tweets! @NeilOConnell

Neil O’Connell is a researcher in the Centre for Research in Rehabilitation, Brunel University, West London, UK. He divides his time between research and training new physiotherapists and previously worked extensively as a musculoskeletal physiotherapist. He also tweets! @NeilOConnell

Neil is currently fighting his way through a PhD investigating chronic low back pain and cortically directed treatment approaches. He is particularly interested in low back pain, pain generally and the rigorous testing of treatments. He also tends to get all geeky over controlled trials.

References

Molsberger AF, Schneider T, Gotthardt H, & Drabik A (2010). German Randomized Acupuncture Trial for chronic shoulder pain (GRASP) – a pragmatic, controlled, patient-blinded, multi-centre trial in an outpatient care environment. Pain, 151 (1), 146-54 PMID: 20655660

O’Connell NE, Wand BM, & Goldacre B (2009). Interpretive bias in acupuncture research?: A case study. Evaluation & the health professions, 32 (4), 393-409 PMID: 19942631

Linde K, Witt CM, Streng A, Weidenhammer W, Wagenpfeil S, Brinkhaus B, Willich SN, & Melchart D (2007). The impact of patient expectations on outcomes in four randomized controlled trials of acupuncture in patients with chronic pain. Pain, 128 (3), 264-71 PMID: 17257756