Editor’s note: This article is part of PRF’s featured content series, “Investigating Virtual Reality for Pain Management: Past, Present, and Future,” which has been made possible thanks to a generous grant from the MAYDAY Fund.

The integration of virtual reality and artificial intelligence is underway and has the potential to transform pain management, healthcare, and our daily lives. Alexiei Dingli – professor of artificial intelligence (AI) at the University of Malta – is an award-winning expert on AI and a successful entrepreneur. He performs research and contributes to the development of AI projects used in education, digital skills, healthcare, and even transportation. Also, as a former mayor of Valletta, the capital city of Malta, Alexiei’s unique background gives him insights on just how effectively virtual reality (VR) and artificial intelligence can enhance our quality of life.

Transcribed below, this interview with IASP’s Associate Director of Publications – Greg Carbonetti – dives into Alexiei’s interests in technology, his appearance on Shark Tank, and his vision of the future for AI and virtual reality in healthcare and daily life.

Would you mind telling us a bit about yourself, and what made you interested in studying these different types of technologies?

I’m essentially a technology guy. I don’t come from the medical side, but of course I have pains like everyone else. I’ve been in AI for the past 20+ years now, and my expertise is in game development, VR, etc. [My introduction to pain management] was more by coincidence, if I must be honest with you.

My team and I developed a VR system, and when we went to present our poster at a conference, there was a presentation on pain and VR from Walter Greenleaf and his colleagues. Now, [their system] was very effective, but I noticed an issue: The system that they presented came only from the “medical side,” and of course they do not have the [same] expertise in VR. I [thought], “I can do better.”

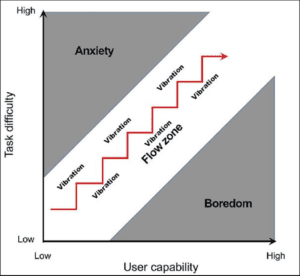

I combined what they were doing with elements of gaming. Now, in gaming, there is something which we call the flow state. What does flow state mean? Essentially, it means the state you’re in when doing something that you enjoy. For example, [sometimes] I start playing a game and [think], “I’ll do a 20-minute game.” Then, I suddenly realize that I spent about two hours playing the game. That’s because I was in a flow state.

We said, “Listen, if we can get the patient into a flow state, [the pain management will] probably be more effective.”

So in 2018, [we conducted research that still used] VR in a similar way – it’s [practically] a game – but what we’re doing is [capturing] biological information about the patient. We got [this] information from smartwatches – heart rate, heart rate variability, etc. – and today, they have many sensors. For example, in the latest version, we also take blood oxygen level. We feed that [information] into a proprietary AI that is on the [VR] headset [and it predicts] whether the person is in the flow state or not.

If the person is maybe a little bit bored, we pump up the intensity of the game so that they move to the flow state. If the person is too pumped up, we slow the game down so that the person is in the flow state. This way, we try to move the person towards the middle, and that proves to be very effective.

In fact, our results show that we managed to reach a 42% pain reduction.

This first project was called Morpheus. Then we had another follow-up project – which we called Precise – where we asked the question, “Once the person gets out of the VR, what happens to the pain?” The pain eventually comes back.

So we asked, “Can we have a system which reduces the pain without the VR?” The answer is yes!

With our second system Precise, we [use] VR where the person is distracted from the pain; however, we are also conditioning the person through the VR. What happens is that once the person gets out of the VR and the pain comes back, they have a watch app [that prompts them to] press a button. [Once they press the button] they get a signal from their watch and their pain levels go down by 40%. It works!

What we do is build that association with their brain. Now, when they are not in the VR and we play the signal back through the watch, we’re getting some good results. Right now, we are polishing the application, and of course we are filing some patents as well. We’re also getting medical certification, and we want to commercialize it.

Bugeja & Dingli, 2023

You’ve done work generating a virtual environment where people can have the experience of autism, but I noticed that you have several similar studies. There was one for the lived experience of being a migrant in a new country, and a recent one on schizophrenia. What was the genesis of this work?

I think it stemmed more from [my] interest in VR, and the technology was becoming much more [advanced]. If I have to be honest with you, the first time I tried VR was in 1996, which was a very long time ago.

I can assure you; I got a terrible headache, and I said I would not do VR again. Now, VR systems have advanced so much more. I’m always fascinated by the ways in which VR can be used to change the brain.

I think it all came from this fascination with how we can mold the brain in such a way to make people better. I think that is a recurring theme in what I do because I believe that if I create AI systems, which ultimately do not touch people for the better, then why am I doing this work? In fact, I have another work in progress [that’s] about trying to understand the EEG signals of the brain and map it into text.

So far, we’ve managed to do 10 words, but we’re expanding it more now to have a vocabulary of bigger words. We’re doing this because of a personal story…. We had a student of ours, and many years later I found out that he was in a motorbike accident and suddenly became paralyzed. So we wanted to give him his voice back. We believe that with this type of system, we can do that. Of course, there’s the technology, the hardware side, but also the software side. For this, we’re using transformers. It’s the basic technology behind large language models like ChatGPT. So these are very powerful AI models, and they’re giving us very good results.

Back to what you [asked]: The migrants’ experience was done because at the time, even in Malta, we had an influx of migrants, and I always wanted people to understand what these people go through. It’s not as if they’re coming on holiday to Malta; they’re risking their lives, and a lot of people do not realize that.

The schizophrenia project started as an educational one as well, as a collaboration with the [Malta] Department of Mental Health. When they train mental health professionals, the way they train them – and this might be funny or tragic, I don’t know – is that someone goes behind the student and starts shouting offensive things. The professionals told me, “That is how [people with schizophrenia] hear the hallucinations.” For them, hallucinations can be auditory, visual, and they can be sensory as well, but for the [patients], they’re as real as both of us talking. They can’t distinguish between what’s real and what’s not.

We said, “Listen, let’s create this VR experience for these mental health students so that we teach them what it would be like.” [In this simulation, the user] goes back to the office after the weekend, and they start getting hallucinations. First, the auditory ones, and then the visual ones. They’re trying to do their job, they’re meeting the boss, but they’re getting these voices telling them, “You’re not good. The boss is going to fire you,” practically pushing them down all the time. Once again, it was a very powerful experience, and you start really appreciating VR.

If you suffer from schizophrenia and you hear the voices, typical therapy forces the patient to confront the voices. So the voices will not go away, but you learn to manage them. What we wanted to do, which was the second phase of that project, was to create these virtual voices, based upon the ones [the user] actually hears, so that [the user] can confront them and even give them a face. Unfortunately, we didn’t get the funding for that phase, but who knows? Maybe in the future….

Recently, we just started another project called VR Mirror Therapy. We’re working with professionals from an eating disorders clinic, and they do mirror therapy. For this, the patient would go in front of the mirror, and must describe their body in fine detail. It’s an exercise in acceptance, so that they learn to accept their body, because the current state of their body is what’s creating the underlying anxiety. It’s about tapping into that. And we’re doing the same now in VR.

You started a company in 2020 initially called HumAIn Ltd. Can you tell us more about this experience and its stated mission to develop “human-centered AI”?

I had started HumAIn because I had won the Malta Social Impacts Award to facilitate creating an AI system for education.

How it started is a funny story. I was helping my kids – I have three kids – do their mathematics, and I, being a lazy software developer at heart, decided to create an Excel sheet that generates exercises automatically, [and] then it corrects them, etc. So my kids had an infinite number of exercises to do. They weren’t so pleased with [“infinite homework”], but they enjoyed it because it gave them feedback immediately.

I [thought], “What if I can do the same for all kids?” This is how my system FAIE [originated], named after my daughter.

With the award, I created the system, and a year later – because of the Malta AI national strategy – it was adopted by Malta. In fact, we’re still working on it, but now we’re extending it to all children in primary school. In Malta, children have a tablet, and the teacher gives out a lesson as usual, but then at the end of the lesson, the teacher presses a button, and every child in class receives a set of personalized exercises based upon their individual abilities.

Then last year in 2024, I was on Shark Tank, and I got funding to create a new company called Digital Traffic Brain, which aims to create systems for traffic management. Right now, we’re rebranding it to Digital Brain, and HumAIn will [most likely] be integrated into Digital Brain. Why? Because what we want to do now is not just focused on traffic.

For example, on the healthcare side, we have a very interesting system called Nurse LUCIE, used for monitoring patients in private and public homes. Basically, it monitors the patients in their wards. So if I wake up in the middle of the night and I have a stroke, the system will realize it, due to the AI analyzing what’s happening, and alert a nurse immediately. The patients also have a wearable device which gives nurses real-time information. So if my heartbeat starts going down suddenly, the system realizes and alerts the nurse. It has a tracker for dementia as well. So if a patient wanders away, the system knows that they are beyond the perimeter, and staff can go and reach them.

I believe that if we create the most fantastic AI in the world, but it’s not being used to help people, then it’s futile. When we create AI that can help people in their daily lives, then I think we are creating human-centered AI. Mind you, I also believe in creating AI that speaks the language of humans, so that people do not need to learn how to use a computer to use these tools. I see this from my dad, since he struggles to use a computer, or any kind of technology, really. But today, we’re moving towards the vocal kind of AI, the one where you can speak to it, and it speaks back.

Do you envision any problems on the horizon as this technology continues to progress?

No. I always say, “AI is a tool.” It depends on how to use that tool. Of course, one of the dangers that I see is that VR and AI together become so good that people might prefer to stay in VR than go to the outside world. I don’t think we should ever move in that direction, like the movie, Ready Player One. This should not be just about creating a good virtual space, but a good space in reality. This is why we want people to stay in their community as well – human interaction is important.

Recently, I was talking to a professor who studies dementia, and he told me that even the preparation to go out is important for the brain – it’s not just talking with someone. So I think that must remain. Of course, if we can assist with AI and VR, I think we should, but try and keep people in their communities.

Having said that, I always say when we are discussing life-threatening systems, or things that might negatively affect people, there should be a gatekeeper, and that should be a human, for various reasons. We’ve seen a lot in the past whereby there were mistakes by an AI system, and the AI system is just following a program. It might be the most intelligent program ever, but it still lacks the common sense, the experience, and everything humans bring to the table.

I always advocate for a balanced approach. So yes, we should have AI, VR, and whatever system that will empower professionals and allow them to do much more than they can do today, but of course the professional is the gatekeeper. So he or she should be there to protect the people from misuse and any dangers.

Where do you see this technology going over the next 10 years in the healthcare space? Is this kind of technology going to be a first-line treatment? Will everyone have access to it?

If I look at what’s happening here in Malta, in Europe, and I would imagine even in the US, we have a big problem with the rising aging population. On the one hand, we have the spectrum of the aging population growing, but we don’t have enough younger people to take care of these folks. So we need to maximize the resources we have, and that is what we are doing with Nurse LUCIE. You still need nurses – I always believe in keeping humans in the loop – but at least we are giving them, like I call them, superpowers.

Before, nurses could watch four people in a room. Now, they can watch 10 rooms at one time, because they’re getting all the information, and probably much better information than by just watching them.

Now, VR is interesting. I always say that we still need to understand its ability. I really believe, from the little I did, that it does change the brain. I’m sure we can do much more than we’re doing, but, unfortunately, sometimes it’s an issue of either funding or technology. For example, one of the problems we’ve been fighting with is getting access to an fMRI, because with it we can prove that our VR is having very positive effects on the pain levels.

I think I see a lot of potential in virtual reality – and not just in virtual reality, mind you. I also see a lot of potential in augmented reality, which could be very helpful as well. Imagine a nurse puts on their glasses, and they can get advice or information about what is happening in a patient’s home, or even just draw attention to the patient who is about to fall. Especially because, I think, we would all prefer that the patient stays at home, rather than go to an institutionalized setting. Of course, that costs even more.

The prominent problem we have now is that the VR headsets are big. We need better technology. And I think once the technology becomes like glasses, then VR will be much more accessible to everyone.

Gregory Carbonetti, PhD, is the IASP associate director of publications and an avid New York Islanders supporter.