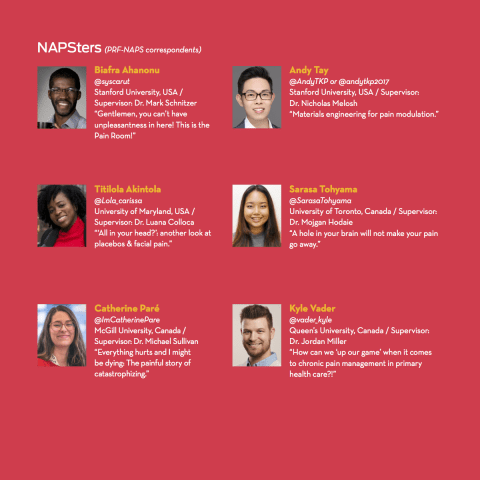

Six early-career pain researchers are participating in the PRF-NAPS Correspondents program during the 2019 North American Pain School, which took place June 23-28 in Montebello, Quebec City, Canada. The Correspondents program is a unique science communications training program that provides participants with knowledge and skills needed to communicate science effectively to a wide range of pain researchers and to patients and the broader public. The Correspondents conducted interviews with NAPS Visiting Faculty, are writing summaries of scientific lectures—and provided live blogging too! Take a look at their blog posts below.

NAPS Recaps

The Train to Pain Is Mainly in the Brain (by NAPS, We Got It!)

Now That I’ve Recovered from My Post-NAPS Nap….

The Top Four Reasons Why You Should Apply for NAPS 2020 (and Be a PRF Correspondent)

From a Feeble Tweet to a Mighty Caw

An All-Around Professional and Personal Development Experience

The Train to Pain Is Mainly in the Brain (by NAPS, We Got It!)

Montreal at night. Visiting Montreal before or after NAPS is a great idea. Photo credit: Biafra Ahanonu.

Montreal at night. Visiting Montreal before or after NAPS is a great idea. Photo credit: Biafra Ahanonu.

Now, once again where is the pain? In the brain! In the brain! – My Fair Clinician (NAPS 2019 Film Festival, Montebello, Quebec, Canada).

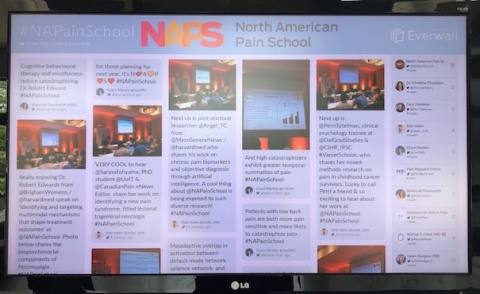

The North American Pain School (NAPS) is a unique experience. The combination of great faculty and trainees, awesome discussions and talks, and a beautiful location help produce a week that will continue to pay dividends far into the future. In this post I want to give future NAPS attendees an idea of why I loved NAPS so much, interspersed with photos that give a feel for what to expect. And for those who want to experience a firehose of NAPS, scroll through the posts at #NAPainSchool. Onward to my NAPS recap!

Faculty and patient partners

The faculty truly took the experience to another level. From enlightening discussions about hype in research with Dr. Jeff Mogil (@JeffreyMogil) to intense chats about calcium imaging with Dr. Michael Gold and a useful workshop by Dr. Christine Chambers on dealing with sexism in the workplace. The rest of the executive committee provided valuable insights: I enjoyed talking with Dr. Roger Fillingim about pursuing passion vs. finding a job and doing it well, along with Dr. Petra Schweinhardt’s workshop in which the NAPSters got to experience several different pain tests themselves (e.g., “To know what kind of pain you’re dealing with”), and with Dr. Charles Argoff, who provided valuable clinical insight.

In addition, the visiting faculty— Drs. Yves De Koninck, Troels Jensen, Judith Paice, Cheryl Stucky, Robert Edwards, and Jennifer Laird—also helped enhance the experience, both from their talks and in discussions with them (keep an eye out on PRF for summaries of their talks). The patient partners Billie Jo Bogden (@BogdenJo) and Justina Marianayagam (@_justinam) provided great insights into the overall experience on the patient side as well as providing needed constructive feedback on both word choice and mindsets of researchers and clinicians; continuing to have patient partners or even a couple more would further improve NAPS.

Networking

(1) Food! There is a lot of great food at NAPS. (2) People apparently hate hip-hop. That is all I learned from the ice breaker (just kidding [but not about the hip-hop]). (3) Faces are hilarious, but pain is not. Much discussion about pros and cons of pain scales during NAPS. (4) The awesome Dr. Roger Fillingim giving a fantastic workshop on mentorship. Photo credit: Biafra Ahanonu.

Networking always sounds so…clinical (pun alert!); however, NAPS could also be known as NAPS (North American Pain Socializing) as it provided one of the best experiences in terms of getting to know both established and up-and-coming researchers in pain. You also gain insights into the different routes people took to become pain researchers, which more often than not appeared to be by chance or unplanned (as I wrote in The Origin of Pain Researchers).

The best thing you can do at NAPS is continuously try to talk to new people. Meet all the trainees! During NAPS I encountered people who work with returning combat veterans, have done veterinary work, interact with patients in rural areas of developing countries, spent time studying obesity and then moved into sleep research, gave me new insights into the culture of Iran, provided a Canadian’s perspective of moving to and living in the (USA! USA! USA!) American South, and talked about their different perspectives on pain having come from a more computational background. And this is only a slice! It is one of the great benefits of NAPS that people from such a broad set of backgrounds are brought to one place where ample time is given to explore and learn.

Pain

(1) The bonfire. For some a way to test their pain thresholds… (2) Maple taffy. This stuff is amazing. (3) Dr. Mogil giving an informative workshop on presenting. Featuring Dr. Allan Basbaum. (4) Effective rhetoric at the student debates. Photo credit: Biafra Ahanonu.

The focus on NAPS was on pain. Going in, I actually thought there would be more wrestling with the never-ending philosophical debate about what “pain” is. While these types of discussions can be useful, it was refreshing at NAPS that pain was treated as, or taken as a given to be, a sensory and affective-motivational percept that we can study objectively. I will write more about this in the future, as it is possible the lack of discussion of what we really mean by pain could be hindering discoveries, but this allowed more fruitful time to learn about all the amazing research going on; to hear about initiatives taking place in the clinic, by patients, and at universities; and to discuss how our understanding of pain could be improved.

In particular, I am still thinking about Dr. Charles Argoff’s workshop, “Interviewing and Diagnosing Pain Patients.” In particular, during the workshop there was a good amount of discussion about asking patients if they have returned to pre-pain function rather than using a quantitative pain scale. While I still have questions about having patients self-report restoration of function (I would have liked to see data showing that patient’s reports agree with assessments by their loved ones, work colleagues, or others who know them), this brought up a good point. It also reminded me of a fun lunchtime topic discussion with Dr. Petra Schweinhardt about the use of functional brain imaging to assess pain and my questions about how it could be used to obtain a secondary verification of pain—inspired by discussions with trainee Saurab Sharma about rural Nepalese claiming to not be in pain (for cultural reasons) while limping away as if they are suppressing a great deal of pain. From this you can get a feel for how various conversations throughout NAPS intertwined with one another to help trainees begin to synthesize the clinical, technological, and cultural aspects of pain to address an urgent issue: how do we measure pain and use it to verify whether therapies are working? This is one of the great benefits of NAPS and I have only highlighted one topic of the many discussed.

Culture and activities

(1) Andy Tay’s birthday celebration. (2) Picture taking, Dr. Mogil edition. (3) Rhetoric at the debates, do we want a “cure” for pain? (See plot of Black Museum). (4) The amazing NAPS crew; ignore the person hogging the left part of the picture. Photo credit: Biafra Ahanonu.

Did you know that, in the course of several generations, Francophone-Anglophone relations have improved even though nearly 25 years ago Quebec came within a hair’s breadth of passing a succession referendum (for those interested, read more here)? NAPS included people from a variety of countries (including Yarim De La Luz-Cuellar from Mexico and Saurab Sharma from Nepal), which helped inform the science (learning how different cultures approached pain, especially in the case of Nepal) and provided a richer background for discussions. At the same time we were able to bond over a variety of activities, such as white water rafting (our boat was known as the “Wave Killers” [“Coming to save the day!”]), where I learned that our guide made the important point that [paraphrasing] “I could either be at home watching Netflix on the weekends or guiding people down the rapids.” These helped break up the intense discussions about pain, leaving me more refreshed and ready to dive back in.

Research

Student talks from NAPS Day 3 (June 25th). Photo credit: Biafra Ahanonu.

Student talks from NAPS Day 3 (June 25th). Photo credit: Biafra Ahanonu.

One of best aspects of NAPS was the student talks. Pain-related cognitive impairment, battlefield anesthesia & acupuncture, epigenome sex differences in pain, dopaminergic pain modulation, parent-child interactions, and more! Future trainees should definitely spend time asking as many people as possible about their research during breaks. You can find out about the various topics discussed at NAPS 2019, but as has been highlighted here, there were a plethora of great talks, workshops, and lectures that will prove valuable jumping-off points at NAPS and going forward after trainees are back home.

I would like to thank Jess Ross (@JRossNeuro) for informing me about NAPS, Neil Andrews (@NeilAndrews) for providing guidance and support as a NAPS Correspondent, and all those who helped organize and coordinate (a special shout out to Drs. Erwan Leclair and Helene Beaudry). NAPS was without a doubt a top-tier experience; from the networking to research to enjoying Quebec, there is much here to offer. Coming from a non-pain lab, Dr. Mark Schnitzer’s at Stanford, NAPS has enhanced the training I received while collaborating with Drs. Grégory Scherrer and Gregory Corder. Prospective NAPSters can get in touch with me (bahanonu@ alum.mit.edu), as I would be happy to answer questions about the program and encourage any trainees interested in pain to apply.

Biafra Ahanonu, PhD, Postdoctoral Scholar, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA.

Above: 2019 PRF-NAPS Correspondents (From left: Kyle Vader, Sarasa Tohyama, Biafra Ahanonu, Andy Tay, Lola Akintola, Catherine Pare). Photo credit: Kyle Vader.

What a week! From morning yoga with Ondine to exclusive trainee workshops, from campfire s’mores to creating my first podcast, NAPS was unlike anything I have ever experienced as a trainee; everything about it was so amazing! A true highlight was meeting and getting to know the faculty, trainees, and patient partners. I will cherish all of the conversations and advice surrounding academia, science, and life, as I continue my journey. Special shout out to my roomie Shahrzad Ghazisaeidi (@Shahrzadghs) – turns out we are both from Toronto (Go Raps)! — to all of the talented PRF Correspondents – I had a blast live blogging and honing our science communication skills together – and to Neil (@NeilAndrews) and Christine (@DrCChambers) for providing such an incredible science communications training program!

Now That I’ve Recovered from My Post-NAPS Nap….

Now that I’ve recovered from an AMAZING week in Montebello, time for a recap of #NAPainSchool 2019 edition! In this blog post, I’m going to focus on my big three “take-homes” from my time at NAPS.

1) The importance of diversity

As highlighted in Dr. Christine Chambers’ (@DrCChambers) talk on “Breaking Barriers: Gender, Unconscious Bias, and Your Career,” diversity matters in science. As I reflect on my week at NAPS, it was so great to have the privilege of connecting with other trainees, patient partners, and pain researchers from across Canada (shout out to @_justinam from the Northwest Territories) and from countries across the world (honourable mention to @atarii_cuellar from Mexico and @Fleurainfleur from Belgium!). I find it so refreshing to hear different perspectives as it always opens my eyes to new ideas and ways of living, which I think is critical in the field of pain research.

2) “Don’t just reach for low-hanging fruit”

The biggest “aha moment” for me from my week at NAPS came from Billie Jo Bodgen (@BogdenJo), one of the #ClassOf2019 patient partners. In her lecture on “Patient Engagement: My Path to Partnership in Pain Research,” Billie Jo ended with an ask that all of us in the audience don’t just reach for low-hanging fruit in pain research, but rather seek out answers to complex problems that don’t always have easy solutions. This message was again echoed by Dr. Cheryl Stucky (@Dr_CherylStucky), who ended her talk, entitled “Animal Models for Pain in Human: Strengths, Weaknesses, and Area for Improvement,” with an “Ode to Billie Jo.” Here she also emphasized the importance of embracing complex problems in pain research.

3) The value of community

Last, but not least, at NAPS I was reminded loud and clear of the value and importance of feeling part of a community. During my time in Montebello, I got to learn alongside a group of people who all share a common interest in improving pain research and care – whether in the context of pediatrics, veterans, or cancer survivors. As I settle back into my work in the School of Rehabilitation Therapy (https://www.rehab.queensu.ca) at Queen’s University, I look forward to keeping in touch with my fellow #ClassOf2019 for support, guidance, and mentorship.

As always, I’ll be continuing to tweet away about my experiences as a physiotherapist and pain researcher, so follow me on twitter (@vader_kyle) and let’s keep the conversation going!

Kyle Vader, PhD student, rehabilitation science, Queen’s University, Canada.

The Top Four Reasons Why You Should Apply for NAPS 2020 (and Be a PRF Correspondent)

I can’t believe it’s the last day of NAPS 2019. I have been to many conferences and several schools as a researcher, but I can confidently say that this is one of the warmest and most welcoming communities I have ever met. Based on my personal experience, I now share with you the top four reasons why you should apply for NAPS 2020 and also the PRF Correspondents program!

1) It’s a unique cultural experience

Whether you need a break, a research inspiration or both, NAPS is a great event to attend. Fairmont Le Château Montebello is a wonderful venue. The food here is amazing regardless of whether you are a fan of BBQ meat, seafood or fresh vegetables. NAPSters also get a chance to know more about Québécois culture during a Sugar Shack dinner! I am not going to reveal how special the dinner is, except to provide the picture below. Do I even need to talk about the jacuzzi?

2

2

2) It’s diverse and inclusive

Jeffrey Mogil, Director of NAPS (and my favorite speaker), shared with us that the NAPSter selection rate was about 25%, with almost complete gender balance and excellent representation of different ethnicities. NAPS also featured pain researchers at different stages of their careers, from first year PhD students to highly accomplished pain leaders. In addition, we had clinical researchers, basic scientists and even engineers like me all gathered in the same room to learn about pain – a truly multi-disciplinary community.

Because of this diverse group, we had the opportunity to learn about pain from different perspectives. For instance, we did an experiment with capsaicin on my arm (see image below), and while it still stings as I am writing, the experience was 100% worth it! More uniquely, we also had patient partners sharing their medical journeys. For anyone who wants to have a once-in-a-lifetime experience learning about pain from multiple angles, NAPS is THE meeting to attend.

3) You can learn “soft” skills

Many graduate programs train their students intensively in experiments, but it is clear that in order for students to do well in their careers and to make an impact on society, they also need soft skills. During NAPS, there were workshops to train participants in skills like managing mentor-mentee relationships, ensuring research rigor, devloping science communication skills and how to present your work like a salesman. These varied skills are especially important for early-career scientists who wish to better communicate their research to peers, the public and future employers.

4) Make friends and build networks

What has been so special about NAPS for me is that the participants are extraordinarily friendly. It has been easy initiating conversations with NAPSters working in entirely different research areas. Faculty members are also extremely approachable. There seemed to be no barriers, which was great for learning and making friends.

An additional bonus if you decide to apply to become a PRF Correspondent is that you would have the opportunity to perform interviews. I decided to interview Professor Cheryl Stucky and, by the way, she blew me away with her exciting childhood stories, sharp insights into pain research and valuable advice about student mentoring. The Eureka! moments and genuine interactions that we shared will be something I will remember for many years to come. Stay tuned for our interview!

I hope that I have convinced you. Start your application early and if you need any advice on your application materials, I am most happy to help. Reach me at andy.csm2012@gmail.com.

Andy Tay, postdoctoral scholar, Stanford University, Stanford, US.

From a Feeble Tweet to a Mighty Caw

“Oh geez, really? This is gonna be painful. I’d really rather avoid it. Okay, I guess I have to suck it up and just do it.”

A glimpse into my mind two months ago would have revealed some variation on those words, but it would not have been related to “volunteering” for a pain assessment workshop (right, fellow NAPSters?). It would actually have been about getting a Twitter account, something I purposefully avoided for a long time. To me, Twitter represented the deterioration of face-to-face contact, time and space for more extensive communication (thank goodness for blogs), and comprehensive knowledge…right?

Wrong! At NAPS, I quickly saw that I had been missing out on a whole community of researchers – not just live tweeting at events like NAPS, but sharing what they learn when they learn it. One of the most validating moments for me at NAPS was when I noticed Billie Jo Bogden (@BogdenJo) sharing my posts, and those posts reaching other people – people I had never met! Not everyone is lucky enough to have access to pain research, but everyone should benefit from it.

I won’t lie and preach that, after six days of live tweeting (check out posts @NAPainSchool, @ImCatherinePare, @vader_kyle, and the like), Twitter had transformed me and that I only speak in 280 character tweets. But Dr. Christine Chambers’ initiative did force me to open my eyes to new and innovative ways of sharing science.

So am I on Twitter every day now? Certainly not, and most days I avoid it. But my views on Twitter and how it might be relevant to science have nonetheless changed. After all, if posting something on Twitter helps even one person deal with their pain, I can certainly get over my own “pain.”

Catherine Paré, PhD student, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec.

An All-Around Professional and Personal Development Experience

Almost every single person is familiar with pain. It’s the most common reason why people seek medical help and is a factor in most diseases and conditions. Thus, we can all agree that understanding pain is pretty important. So when 30 pain trainees go off to meet with 12 of the most established pain researchers amongst the beautiful maple trees of Quebec…you can just imagine the magic that’s bound to take place.

This was exactly what #NAPainSchool was. The people, the science, the use of technology, the food, the connections—all of it came together to form the most comprehensive professional and personal development experience of my academic career thus far. Every day was truly unique in the message that it brought home but a common thread that ran through it all is the importance of tackling the big, complex problems and the need to look at problems from different sides and with great compassion. From the yoga sessions to the insightful talks, to the workshops on skills and interpersonal relationships and much more, it really was an intensive, all-around experience. Very quickly a community was built and by graduation day, we all felt like a family. This is the magic of NAPS!

I’m not sure I knew everything to expect coming into NAPS 2019 but I certainly left with a lot. What I have come away with is a deep sense of community, a greater sense of pride in the work that we do, and, most of all, a wealth of scientific knowledge and new ideas about my own work.

I feel so privileged to have been able to learn from the faculty and other NAPSters. Special thanks to @IASPpain and @PainResForum, the executive and planning committees, and all the sponsors for making this experience truly worthwhile. I look forward to being part of this family for a long time.

Titilola 'Lola' Akintola, PhD student, University of Maryland, Baltimore, US

Wednesday, June 26, 2019

Pain Testing in Humans (Is Quite Painful!)

Speaking and Writing About Your Science … IT MATTERS!

What’s the Deal with Having Patient Partners in Scientific Meetings?

Writing About Your Research for the Public: “Pain in the Brain” Edition

Tuesday, June 25, 2019

Pain Treatment During the Opioid Crisis

How to Be a Good (Pain) Trainee in Five Steps or Less!

Pain Assessment in Research Versus Clinical Practice: A Disconnect

“Well, This Is Quite a Pickle”

Calling All NAPSters: Preprints to Accelerate Pain Research!

Monday, June 24, 2019

The Origin of Pain Researchers

On the Nature of Chocolate Mousse

Trainee Talks Were a Highlight of the First Full Day of NAPS

The Vast and Diverse Field of Pain Research

Yoga, Pain Science & Tweeting … OH MY!

Pain Is Complex: Here’s How Engineers Can Help

NAPS Previews

Moving My Research Forward With the Help of NAPS

Summer Camp for Adults Studying Pain?!? Sign Me Up!

The Spiritual, Societal, and Historical Milieu Influencing Pain Perception

Wednesday, June 26, 2019

Pain Testing in Humans (Is Quite Painful!)

As we were all summoned into a small room, I lifted my sleeve and stuck out my forearm, where one of the faculty members applied a bright orange cream in a circular fashion. The capsaicin didn’t feel like much at first, but as time progressed, it started to itch, prickle, and then burn. This exercise was part of our afternoon workshop on “Pain Testing in Humans,” hosted by Dr. Petra Schweinhardt.

We had three different stations: The purpose of the first station was to measure hyperalgesia and involved using a thermal stimulus to test whether the area of primary hyperalgesia felt more painful than the surrounding areas. I jolted when the heat stimulus was applied to the primary zone and was quite surprised by the stark contrast to when the same stimulus was applied to my other forearm, which still felt painful but did not result in an extreme and exaggerated reaction.

The purpose of the second station was to measure pain distraction and involved immersing our hand in an ice water bucket set at 5 degrees Celsius. We were asked to rate our pain on a Visual Analog Scale while our hand was immersed, as well as during and after a Stroop task. My group felt the distraction of the Stroop task masked our pain from the ice water. As soon as we finished the task, our pain shot up!

The purpose of the third station was to measure conditioned pain modulation and involved taking a baseline rating of pressure pain from our thumb and immersing our arm in the ice water bucket for 2 minutes. Our pressure pain was also recorded during and after the immersion in ice water. Consistent with the phenomenon of “pain inhibits pain,” the majority of my group had lower pressure pain ratings during the ice water immersion. The 2 minutes also felt a lot longer and left some of us sweating at the end!

Overall, for trainees that have not had exposure to how pain testing is conducted in humans, it was a fun and interactive learning experience!

Sarasa Tohyama, PhD student, University of Toronto, Canada.

Today, NAPSters were treated to a great deal of stellar science communication lessons. From how to write articles to different audiences, to how to give excellent talks, it was a welcomed crash course in “how to be a science rockstar,” if you will.

Neil Andrews, expert science writer and the Executive Editor of the Pain Research Forum, told us to consider the idea of “opening things up” as opposed to “dumbing things down” when writing to a general audience. In his really enlightening and humorous session, he also very strongly advised against scientific jargon and getting lost in the weeds (or fine details). For a more general audience he recommended applying a different approach than what is typically used in scientific writing for journals by immediately starting with the bottom line and stating the significance of the findings or study before writing about the relevant details. Regarding the most complicated scientific concepts, he recommended breaking things down completely into component steps (again, with no unnecessary jargon).

On giving a great talk, Dr. Jeff Mogil, the Director of NAPS and a professor at McGill University, emphasized “style over substance”

Here is a summary of 6 key tips from his talk:

1. “The science will speak for itself”: those who will believe your story won’t immediately care about the minute details and those that will care can always check out the cited papers afterward if they need to.

2. Focus on selling your story: On that stage/podium, you’re not a scientist. Rather, you’re an actor, a salesman or both.

3. An actor always memorizes his or her lines. So in front of an audience, you shouldn’t read your slides or need words to cue you in. The slide itself should be enough to cue you in.

4. For that to happen, you need to practice your talk. A lot! You can have talks of different lengths about your research that you practice often and can modify to fit a specific need.

5. Don’t bite off more than you can chew. You don’t have to discuss or highlight every single thing. It’s okay to leave certain things out and decide what details to include in order to fit within the time allotted.

6. Don’t go over time—just don’t do it!

Here’s to honing our crafts and becoming better writers, speakers and science communicators! Keep up with updates on Twitter using #NAPainSchool.

Titilola 'Lola' Akintola, PhD student, University of Maryland, Baltimore, US

Speaking and Writing About Your Science … IT MATTERS!

Our third full day of NAPS is here!

Today kicked off with a lecture by Dr. Troels Jensen from Aarhus University. Dr. Jensen’s talk focused on risk factors for the development of chronic pain, and focused on whiplash, post-surgical pain, and diabetic neuropathy. Check out an article (cited over 2900 times!!!) co-authored by Dr. Jensen on risk factors and prevention of persistent pain after surgery published in The Lancet here.

The next workshop of the morning was led by Neil Andrews (@NeilAndrews) of the Pain Research Forum on “Writing for the Public: How to Write about Your Research to People Without (and With) Science Degrees.” There was six key points on writing from this workshop: 1) Don’t dumb it down; instead, open up your science to a broader audience; 2) AVOID JARGON!!!!! 3) State your bottom line up front; 4) Don’t get lost in the weeds; 5) Break scientific concepts down step by step; and 6) be entertaining!

The final session of the day was led by Dr. Jeffrey Mogil (@JeffreyMogil), Director of NAPS, on “Style over Substance: Giving Better Talks.” A key take-home message for me was that giving a talk is as much about “how you say it” as what you are saying. Part of this session involved NAPSters going up to the front of the room and getting feedback (bless those brave souls!). Speakers included: Ali Alsouhibani (@Ali_Alsouhibani) on “Does Exercise Inhibit Pain? Let’s Get Psychophysical," Biafra Ahanonu (@syscarut) on “Pain in the Brain,” Larissa Strath (@larissastrath) on “Diet and Pain: You Feel What You Eat,” and Nicholas Giordano (@nagiordano) on “Assessing Pain from a Patient Perspective.”

Honourable mention from today’s activities also goes to important lunchtime discussion with NAPS patient partners Billie Jo Bogden (@BogdenJo) and Justina Marianayagam (@_justinam)!

Kyle Vader, PhD student, rehabilitation science, Queen’s University, Canada

We have a problem in pain research, and it’s becoming increasingly serious.

I don’t mean that the pain research world is plagued by inadequate methodologies, a lack of rigor, or unethical procedures. I mean that pain researchers are failing to fulfill their complete responsibility – giving research back to the people.

After all, who is scientific research funded by, at least in North America? The citizens of its respective countries, through the government. That means that the 40-year-old mom of 3 living with chronic back pain is paying for the development of your magnetic biomaterials for neural modulation. And the 23-year-old university student suffering from Crohn’s disease is paying for bettering your understanding of pain management in primary care. Do we not owe these suffering individuals deeper insight into their pain experiences and the translation of research into clinical practice?

Neil Andrews, the editor of the Pain Research Forum, gave an excellent presentation and workshop for the NAPSters today on how to communicate to those with and without science degrees. He delineated a number of ways to be good science communicators, but the first steps start with us, the researchers. It is crucial for the continued advancement of pain research that the public (and our fellow researchers!) know what we are doing. NAPS is promoting this throughout the PRF-NAPS correspondent blogs, as well as by encouraging tweeting during the event. Follow #NAPainSchool to see how budding pain researchers are answering the call to give the people the knowledge they deserve.

Catherine Paré, PhD student, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec

What’s the Deal with Having Patient Partners in Scientific Meetings?

NAPS 2019 is my second scientific meeting with patient partners. My very first was a conference on cancer immunology where I learned that not only can adoptive T cell therapy be cytotoxic due to excessive release of cytokines, but also that it can incur financial toxicity. My conversation with patient partners made me reflect hard on how, as a scientist, I can help lower the financial barriers to promising biomedical treatments. That experience has inspired new ideas and my research has definitely benefitted from it.

I believe that many scientists, including myself, do not interact with patients on a daily basis. This is especially true for basic science researchers who mostly work with cells, tissues and animals. However, there are so many benefits that accrue from interacting with patient partners. Besides getting new ideas for research, it provides researchers with a platform to understand the urgency of innovations in their research and the actual impact their work can have. It can also help inspire researchers who have been working on the same topic but are making slow progress. Overall, having patient partners provides a more integrated approach to solving healthcare problems, where biomedical innovators receive feedback directly from their target audience.

Nevertheless, it is still relatively uncommon to have patient partners at scientific meetings. Discussing with Billie Jo Bogden, one of the patient partners at NAPS 2019, we came up with some suggestions to better promote patient engagement:

1. Volunteer your time to share your knowledge. Many non-profit and healthcare institutions organize volunteering activities. As scientists, we can volunteer at meetings and other events to share our knowledge about the latest research findings with them. Interacting with patients can also help train researchers to make research data relatable and relevant to them – a very key aspect of communications that graduate programs do not train us adequately for.

2. Start doing science communication. Do not worry if you are not a fan of writing. Science communication can come in many forms such as images, videos, phone apps, toy kits and even lab tours.

3. Write to conference organizers on the importance and benefits of having patient partners and request that these organizers sponsor a few patients who will share their experiences as speakers. In fact, professional societies are starting to include patient partners in their meetings and workshops.

4. Join special interest groups with patient partners to create learning opportunities for one another.

I would like to dedicate this blog post to our NAPS 2019 patient partners, Billie Jo Bogden and Justina Marianayagam, to show how much I appreciate their invaluable input to help in the fight against pain.

Andy Tay, postdoctoral scholar, Stanford University, Stanford, US

Writing About Your Research for the Public: “Pain in the Brain” Edition

Photo by Dan Dimmock on Unsplash

On Wednesday of NAPS we had a great workshop by Neil Andrews titled “Writing for the Public: How to Write About Your Research to People Without (and With) Science Degrees.” This workshop had an interactive component where we had an opportunity to quickly write up a public-friendly description of our research and then receive feedback from another trainee (thanks Yarim De La Luz-Cuellar [@atarii_cuellar]!). Below I have included this write-up with minimal edits. You can contrast it with a more long-form article on Practical Pain Management that I was involved with (Scientists Pinpoint Brain Circuit that Mediates Pain).

Why do some people love the Arizona heat (that’s me!) and others crave the “beautiful seasons” in the Northern parts of the United States? Why do people respond to the same stimuli in a different fashion?

I am interested in how the brain takes external stimuli, decides on whether to make stimuli enter conscious awareness, and determines what actions to take in response to those stimuli. Think of a touch from a loved one eliciting a reciprocal response or shifting in your feet once I point out that you feel pressure there. There are multiple fields in neuroscience that seek to address this question. My current research focuses on how the unpleasant component of pain arises and how the activity of individual neurons leads to the suffering associated with pain. This interest comes both from seeing a loved one suffer from persistent pain and an interest in the basic mechanisms of this widespread, clinically costly, and fascinating sense.

We have taken a multi-pronged approach to answering the question of how the brain turns external stimuli into an unpleasant pain perception. First, we use small, miniature microscopes attached to animals’ heads to record the activity of hundreds of neurons in a region of the brain called the amygdala, which means ‘almond’ (like its shape in the brain!). You might have heard of this region for its role in emotions. We found neurons that responded to painful stimuli. Using computational techniques, we could use neural activity to predict whether animals had been given a painful or non-painful stimulus—like a computer being able to read your brain or emotional state. Further, the level of activity of the pain neurons predicted how likely the animal would be to respond to a given stimulus—like a dial that would turn the ‘pain’ up or down.

We then thought, what if we turn the dial all the way down? Using new technology, we turned the activity of pain neurons down and then observed the animals’ behavior. We saw that the animals still reflexively responded to painful stimuli but did not show other behaviors associated with suffering. Imagine placing your hand on a bed of needles and feeling the pricks, but not finding it unpleasant!

Our research adds to a growing pool of knowledge that seeks to identify how the coordinated activity of individual neurons produces pain perception. It’s akin to investigating how the individual band members in an orchestra help produce Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9. In the future we hope to learn more about these pain amygdala neurons, for example, what genes they express, what other brain regions they interact with, and more—and if a similar set of pain neurons exists in humans, whether they have therapeutic potential.

Biafra Ahanonu, PhD, Postdoctoral Scholar, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA

Tuesday, June 25, 2019

Pain Treatment During the Opioid Crisis

Effectively treating pain in the time of an opioid crisis: this is one of the themes that has stayed in my mind as the 3rd day of NAPS wrapped up. As a person who spends a great deal of time thinking about and studying the dangers of opioids and the need for non-pharmacological alternatives for pain, today was a reminder that in some populations and demographics, the conversation around pharmacological analgesics takes a very different tone.

Dr. Judy Paice, a nurse, researcher and Director of the Cancer Pain Program at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University shared an excellent talk on the several considerations for pain management in cancer patients. With specific case studies, we saw how the opioid epidemic and changing regulations around that may have substantially reduced pain management options for cancer patients. She highly recommended screening, and individualized risk assessment, in determining appropriate pharmacotherapy for cancer survivors as well as a compassionate approach to those at risk for or with substance use disorders.

In the developing world, the outlook on opioids is substantially different. First, @link_physio’s research from Nepal already gave us the understanding that there are cultural differences in pain expression and adjustments in assessment need to be made to accommodate that. Then we got to sit at a lunch table discussion with Dr. Paice and Dr. Allen Finley, a pediatric anesthesiologist, both of whom are heavily involved in global health work in the pain sphere, to continue this discussion. In these places, the conversation around opioids is less about the dangers and more about their scarcity and getting access to them for life-saving surgeries, despite regulatory and political impediments.

The importance of understanding a problem from different perspectives and hearing from others cannot be overemphasized. If, like me, you would appreciate some “light” reading about the opioid crisis, check out some recommendations below. Stay tuned for more at @Lola_carissa and follow updates on Twitter using #NAPainschool.

Titilola 'Lola' Akintola, PhD student, University of Maryland, Baltimore, US

How to Be a Good (Pain) Trainee in Five Steps or Less!

In the past three days, I have learned that I still have a lot to learn.

It’s easy to feel that we should be established researchers when we are surrounded by the top investigators in the field as well as by aspiring, ambitious, and awesome peers! But is it really that simple to be a trainee? It seems to me that what’s actually easy is to become lax in our enthusiasm for conducting top-quality research. However, being a trainee doesn’t have to be this way, so here are the top 5 things (from NAPS so far, at least…) to do to become a better trainee:

1. Become a mentee! Dr. Roger Fillingim stressed that it is the responsibility of the mentee to find a mentor! Mentors are invaluable in a trainee’s research journey, from helping to solve methodological problems to providing emotional support.

2. Include patient partners in the picture. The faculty members debated amongst each other whether this is relevant for all kinds of researchers (including basic scientists). A number of trainees presented results from qualitative research highlighting the necessity of including patients in the dialogue driving research initiatives.

3. Collaborate with all kinds of researchers and move the debate away from “basic versus clinical research.” Without our fellow pain researchers to move ALL of pain research forward, the discipline as a whole suffers.

4. As per Dr. Michael Gold, promoting scientific rigour and reproducibility is imperative for conducting good research. Trainees need to remain aware and vigilant of the need to do good work in order to promote the integrity of pain research in the future.

5. In the words of Dr. Charles Argoff during his workshop on assessing and diagnosing pain, “be humble.” We do not know everything about chronic pain, and need to accept that we should always be trying to improve.

These are just a few (non-comprehensive!) steps to becoming a better trainee…stay tuned for more at #NAPainSchool!

Catherine Paré, PhD student, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec

Pain Assessment in Research Versus Clinical Practice: A Disconnect

Day 3 of NAPS kicked off with a talk by Dr. Judith Paice from Northwestern University on “Cancer Pain in the Time of an Opioid Epidemic.” Her encouragement to always take a compassionate approach to pain management left us all thinking about why research on cancer pain is relevant for all pain researchers. I had the privilege of sitting down with her later in the day to further discuss this topic. Stay tuned for my first-ever podcast and insights into pain, opioids, and the media!

One interesting perspective Dr. Paice mentioned during her talk was that the way pain is typically assessed in the clinic is by asking about the patient’s function and goals. This is in contrast to how pain is assessed in research, where scales such as the Numerical Rating Scale are used to measure pain intensity from 0–10 (0: no pain; 10: the worst possible pain). The question period resulted in an eye-opening discussion about a disconnect between research and clinical practice. Indeed, in a later workshop on “Interviewing and Diagnosing Pain Patients,” Dr. Charles Argoff revealed that in his clinical practice, he largely ignores pain assessment scales such as the Numerical Rating Scale and Visual Analog Scale and primarily focuses on the patient’s function. Of note, he stressed the importance of letting patients describe their pain in “their” terms. As a graduate student who conducts pain research in patients and healthy individuals, this got me thinking about the translational importance of assessing pain in a way that reflects both the clinical practice and research worlds.

Tomorrow’s schedule is filled with more talks and workshops from the faculty – I look forward to continuing to learn about pain and its neglected problems! You can follow #NAPainSchool on Twitter for live updates.

Sarasa Tohyama, PhD student, University of Toronto, Canada

”Well, This Is Quite a Pickle”

The focus of today’s blog will be the lunchtime breakout session I attended, led by Dr. Christine Chambers (@DrCChambers). The topic was “Knowledge Translation/Mobilization in Pain Research.” P.S. – you’ll understand the title once you reach the end of my post!

There are SO MANY things I could write to summarize this session, although I’ll do my best to keep to the point.

1. At its core, knowledge translation is about moving new knowledge from research into the hands of the right end-users. You can check out a great resource on knowledge translation from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research here.

2. Knowledge translation is hard for a person to do alone. As described by Dr. Chambers at our discussion table today, partnerships and relationships are KEY to success. Furthermore, as with any relationship, it can take time to make connections – so be patient!

3. Not every researcher can (or wants to) do knowledge translation, and sometimes this can be for good reasons. For example, there can be many challenges in obtaining research funding to support knowledge translation initiatives, and furthermore, many researchers may not have the skills to effectively disseminate knowledge.

4. For trainees (whether from a basic science or clinical research background), there is tremendous value in engaging in mutual partnerships with patient partners. The sooner you can do it, the better! Check out a resource on patient engagement in research developed by the University of British Columbia and Arthritis Research Canada by clicking here.

In sum, knowledge translation is no easy task. As summed up nicely by fellow PRF-NAPS Correspondent Catherine Pare (@ImCatherinePare), “Well, this is quite a pickle.” Despite the challenges, as pain researchers, it is critical that we look at ways to ensure new knowledge is translated into the hands of those who need it, including healthcare providers, policy makers, patients, and the public at large.

Kyle Vader, PhD student in rehabilitation science, Queen’s University, Canada

Calling All NAPSters: Preprints to Accelerate Pain Research!

Research is time consuming – not only the experimental aspect but also the peer review process. If you take a careful look at papers, you will often notice a gap of a few months to even a few years between paper submission and acceptance, and this does not even include the time for previous submissions, revisions and rejections. I would like my fellow NAPSters to know a bit more about how preprints can help them. (Disclosure: I am a consultant for bioRxiv and really enjoy it!).

What are preprints?

Preprints are papers that have not undergone peer review but, nevertheless, are scientifically useful. They are meant to accelerate the visibility of research and to make research discoveries accessible in a more timely manner and, importantly, they are free-of-charge to publish and read. In fact, the physics community has embraced preprints for quite some time through their flagship server, arXiv. bioRxiv, the preprint server dedicated to biomedical sciences, started a few years back, and is rapidly growing.

The Pain Research Forum recently started highlighting pain-related preprints through its Papers of the Week feature. This idea came about after feedback from readers of PRF. Although preprints are becoming more popular, it can still be terrifying for someone new to them. Some of the most common concerns are: 1) Will my paper be scooped? 2) Will my paper be rejected if it first appears as a preprint? and 3) Do grant agencies recognize preprints?

The short answers to these 3 questions: 1) Unlikely; 2) Very unlikely but important to check each journal’s policy; 3) Definitely a YES!

How does bioRxiv work?

Let’s take a look at what goes on at bioRxiv after a preprint submission.

Once a paper is submitted to bioRxiv, it will join a queue of new papers. Papers are first screened by a group of consultants, including myself, for their format such as author information and required headings. Papers with incorrect formats are returned to authors so changes can be made. Papers that are deemed inappropriate, such as those having insufficient new data or commercial interests, or papers that are unethical, will be rejected.

Next, papers are sent to affiliates – scientist volunteers who will then evaluate the scientific soundness of papers before letting papers “go live,” i.e., before they are made accessible to the public.

Whenever the authors wish to update their papers, they can initiate revisions. For revisions without significant changes to research conclusions, the papers will be screened only for their format before going live. The turnaround time from submission to online availability is usually less than a week.

Interested about preprint submissions but still have other concerns? Then head to the bioRxiv FAQ web page to learn more!

Andy Tay, postdoctoral scholar, Stanford University, Stanford, US

Monday, June 24, 2019

The Origin of Pain Researchers

Above: Evening bonfire at NAPS. Photo credit: Biafra Ahanonu.

Why pain?

Or more specifically, why pain research?

It might seem that everyone’s route to pain research originates from the lofty goal of discovering cures and treating patients. But in conversations with several participants at the North American Pain School (NAPS), it is clear that is not always the case and that there are many routes to pain (research!).

There are many examples. One person, applying for graduate school, had a list of professors they wanted as mentors, sent letters of interest via mail (yes, snail mail!), and it so happens one of them did pain research. That led to a lifelong career in pain. Another started off doing toxicology and then transitioned to pain research. There are those with a more clinical background (physiotherapist) or experience dealing with wounded American soldiers coming back from tours abroad, which some would view as a more direct path to pain research. Still others started their careers by attending a lecture delivered by an established researcher within the field that jumpstarted their interest in pain. Lastly, an obesity researcher switched to studying sleep, which happens to dovetail nicely with pain research due to the effects of sleep and pain on one another. This gives a feel for the variety of routes people have taken to get into pain (research!).

During the evening workshop, Dr. Roger Fillingim started an extremely helpful discussion around mentorship (read Mentorship in Academic Medicine). This reminded me of a personal blog post I had written long ago on resources useful to graduate students (Graduate Student Resources) and how useful it is for professors to formally give resources and run workshops to get people thinking about mentorship in a more in-depth fashion. In the future, this type of workshop might also be an opportunity to talk about how future and current mentors can bring more people into the pain field, as oftentimes mentors in fields you aren’t familiar with can spark hidden interests that turn into lifelong passions.

The first couple days of NAPS have been awesome. There have been great conversations ranging from the role of hype in pain research (be mindful [hint hint] of this!) to bringing a Buddhist monk or another spiritual teacher into next year’s NAPS to give their perspective on pain, and beyond. And as an American, it has been great hearing about all the different programs taking place here in Canada (e.g., Solutions for Kids in Pain [SKIP]), both within the basic research, patient, and clinical science communities. These are all more reasons to do pain research, because of the fantastic and intellectually stimulating community.

Really looking forward to the next couple of days. As always, follow updates via Twitter using #NAPainSchool!

Biafra Ahanonu, PhD, Postdoctoral Scholar, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, US

On the Nature of Chocolate Mousse

When I was preparing for NAPS, a trusted source informed me that one of the things I should most look forward to during my time at Montebello was the chocolate mousse. This chocolate mousse, I was promised*, would be exquisite: melt-in-your-mouth chocolate, light as air and full of rich, deep flavour that would bring to the consumer pure joy. Safe to say, my expectations were high: I thought that the chocolate mousse would be very exciting and novel, but also reliable and safe.

Another subject that was also reliable and safe but that I felt I might get a new and interesting perspective on was pain catastrophizing. Catastrophizing is one of the most well-established psychosocial risk factors in pain research. I thought that by getting to hear from Dr. Robert Edwards about his research on catastrophizing, as well as by receiving feedback on my presentation about catastrophizing from NAPSters and faculty members, I would be exposed to new opinions and ideas about the construct I knew well…but boy, was I in for a treat!

The recurring dialogue of how important catastrophizing is in pain was catapulted into the future of pain research by none other than Billie Jo Bogden, NAPS patient partner and advocate extraordinaire. She fearlessly stood among her NAPster colleagues and reminded us of the power our research terms have on those we are trying to help, the patients. The term "catastrophizing" has been felt as a pejorative by patients, and no solution has yet been proposed. By highlighting this issue, I think Billie Jo Bodgen reminds us it is imperative to include patient partners in pain research and ensure that we are not hurting those we are working to help.

While I haven't yet tried the chocolate mousse at NAPS, after my learning experiences today, I might do better to step outside of my comfort zone and try something different.

* Some embellishments have been made by the writer about the source’s opinion of the chocolate mousse.

Catherine Paré, PhD student, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec

Trainee Talks Were a Highlight of the First Full Day of NAPS

The first full day of NAPS was filled with AWESOME talks from trainees, which will continue on Day 2. We have an incredibly diverse group not only with regard to where we all come from and receive our training (so far, I have met trainees from my hometown of Toronto, all across the U.S., and Belgium!) but also with the specific areas of pain we study. These talks featured topics ranging from pre-clinical animal models of pain to study chronic itch, stress, and the “standard American diet”; to pain across the lifespan including research on premature infants, childhood cancer survivors, and older adults; to the application of emerging technologies including advanced neuroimaging, machine learning, and programmable magnetic biomaterials to understand and treat pain.

These talks, including the wonderful talks from the visiting faculty, culminated in a rich discussion that aligned with the theme of this year’s NAPS, which is “Biggest Neglected Problems in Pain Research… and What To Do About Them.” Some of the larger points that we discussed thus far that tie into this theme are 1) the importance of time, particularly a longer duration of pain from injury, in animal models of pain and 2) the challenge of moving findings about effective pain management to actual practice (according to Dr. Christine Chambers it can take 17 years for research to make its way into practice!). I am beyond excited for the remainder of the talks from the trainees and faculty and look forward to further exposure to the diversity of pain research here at NAPS! Stay tuned at #NAPainSchool.

Sarasa Tohyama, PhD student, University of Toronto, Canada

The Vast and Diverse Field of Pain Research

The first full day of NAPS began with yoga and smoothies out in the morning sun with our yoga teacher and “zen-master,” Ondine. It was a nice start to the day because after that, we quickly got into the swing of things by hearing from all the NAPS executive committee members and from about half of the trainees (aka NAPSters), who spoke about their lines of research.

The first thing that stands out is how vast and diverse pain research is and the beauty of a meeting like NAPS is the multidisciplinary lens with which one gets to see everything. We were introduced to everything from the receptor mechanisms of morphine-resistant pain, to how early life pain in premature babies is related to osteoarthritis pain later in life, to mechanisms of chronic itch! The diversity is rich and the little 5-minute snapshots from the NAPSters into what we are all working on leaves you wanting more, and I know that for me it inspired lots of mingling and more conversation after each session.

I was especially looking forward to hearing Dr. Cheryl Stucky’s talk on the strengths and weakness of animal models in pain and the factors to consider to improve translation. I’ll also be touching on the subject as part of my student talk; and I was glad to have a nice premise.

Finally, the lunch topic discussion I participated in tackled the problem of making non-pharmacological pain treatments scalable and more accessible and this really sparked a great discussion, which was led by Dr. Robert Edwards. We identified some of the different challenges, including patient compliance, support of health care practitioners, as well as the shortcomings in making alternative therapies/technologies fully available to the public after scientists complete their research studies. We highlighted patient literacy and education as one possible first step to bridging some of these gaps.

Another full day of learning awaits tomorrow. For those on Twitter, feel free to follow the conversation using the hashtag #NAPainSchool to stay up to date.

Titilola 'Lola' Akintola, PhD student, University of Maryland, Baltimore, US

Wowzers!! The first official full day of the 2019 North American Pain School has been JAM- PACKED with awesomeness so far. The day started off with yoga with Ondine (check out our downward dog here) and was followed by fantastic talks, by executive committee members, visiting faculty members, and NAPSters.

A big take-home message for me has been the DIVERSITY of pain research that is being conducted by those at NAPS. As a physiotherapist and PhD student in rehabilitation science focused on chronic pain management in the context of primary health care, it can be very easy to stay in my own “bubble” of pain research.

Demonstrating some of the diversity of research being done by those at NAPS, some of today’s talks have focused on pain in childhood cancer survivors (by PhD student @PerriTutelman of Dalhousie University), identifying a new type of chronic pain condition (by PhD student @SarasaTohyama of the University of Toronto), and the use of biomarkers and objective diagnosis of pain through artificial intelligence (by post-doctoral researcher @angel_TC of Harvard Medical School).

In addition to hearing about innovative pain research, one of the best parts of today has been the informal and impromptu conversations – with visiting faculty members, other NAPSters, and patient partners. A big part of this has been getting to know the people behind pain research. I must admit that I’m impressed not only by the pain research being undertaken by those at NAPS, but also by the character of the people who are doing this important work.

For those who follow me on Twitter (@vader_kyle), you’ll see I’ve been tweeting away. Once again, don’t forget to use the NAPS hashtag #NAPainSchool to stay up-to-date on what’s happening this week in Montebello!

Kyle Vader, PhD student, rehabilitation science, Queen’s University, Canada

NAPS PREVIEW BLOG POSTS:

Have you ever gotten lost while travelling somewhere new, only to find yourself in an exciting and unique place?

This happened to me once, when I was travelling around Pai, Thailand. One minute I was scootering down the road, unsure of where I was going; the next I found myself on the edge of an incredible tree-filled canyon, stretching and curving across a vast swath of land. Naturally, I stopped to admire the sheer beauty of the space, but hesitated to take my first exploratory steps into the canyon.

NAPS feels similar to me in so many ways to that strange and fascinating experience in Pai. When I started my PhD two years ago, I was unaware that pain research was becoming increasingly prioritized and that the presence of schools for pain research trainees was rapidly growing. Even one year ago, I had only heard whispers of the elusive NAPS, saying things like, No one gets in, it’s so popular or Getting in is impossible, don’t even bother…

Luckily for me, I met a real-life NAPS graduate six months ago. She regaled me with tales of how amazing her experience with NAPS was: You HAVE to apply! It’s life-changing. She described the multitude of benefits of participating in the program, like interacting with and learning from patients who actually live what I research as a clinical psychology student. So I applied, cautiously, feeling a little bit lost, and uncertain of what might lie ahead.

And now here I am, not so lost anymore. I have found the canyon, and stand on the precipice of this exciting, wonderful, and unexpected experience. With this entry, I take a step towards the canyon, ready to explore, with one question on my mind: What opportunities lie ahead?

Above: A canyon in Pai, Thailand.

Catherine Paré, PhD student, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec.

Moving My Research Forward with the Help of NAPS

Hello everyone, this is Andy! I am a postdoctoral scholar at Stanford University. I am super excited to be part of NAPS and the PRF-NAPS Correspondents program.

I learned about NAPS in 2017 but I was two months late. The next year, I kept a calendar reminder for the entire month of January so that I wouldn’t miss this opportunity again.

My research focuses on using biomaterials for remote cell modulation. In my work, I have found that after chronic mechanical stimulation, dorsal root ganglion neurons express fewer mechanosensitive ion channels. These are proteins sandwiched in the cell membrane and can be activated by mechanical force. In certain sub-types of pain, there are too many of these channels, and when this happens, neurons become too sensitive to mechanical stimuli. One example of this is mechanical allodynia, where light touches can induce pain.

To move my research forward, I hope to learn about animal models of pain and state-of-the-art methods for pain modulation during NAPS. I believe that this knowledge will allow me to refine my ideas for using biomaterials for pain relief.

My research has also gathered significant media attention. I have even received emails from patients asking whether my technology can help them. In their emails, I sense desperation and frustration, and these emotions motivated my application for NAPS and for the PRF-NAPS Correspondent program. Through these unique platforms, I aim to interact with stakeholders like pain researchers, healthcare professionals and patients to better integrate myself into the pain community. Pain is a highly complex condition and to effectively manage and cure it, we need input from different angles and perspectives.

I feel extremely fortunate to be chosen for NAPS and as a PRF-NAPS Correspondent. Please stay tuned for my future blog posts!

Andy Tay, postdoctoral scholar, Stanford University, Stanford, US

It’s hard to believe the time is almost here…North American Pain School 2019! I found out I was accepted into NAPS while attending the Canadian Pain Society’s Annual Scientific Meeting this past April in Toronto (#CanadianPain19). I’ve heard such great reviews from previous NAPSters about their experiences, so I’m thrilled to be part of the Class of 2019!

First off, a bit about me. I’m a physiotherapist and have just finished my first year of PhD studies in rehabilitation science at Queen’s University under the supervision of Drs. Jordan Miller and Dean Tripp. My research focuses on pain, primary healthcare, and knowledge translation. My first experience in the world of pain was during my final clinical internship as a physiotherapy student, where I was lucky to spend five weeks in the Pediatric Chronic Pain Clinic at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. This was a transformative experience for me and sparked my interest in pain research and care.

The agenda for NAPS 2019 looks fantastic. The theme for this year is the "Biggest Neglected Problems in Pain Research … and What To Do About Them." As a PRF Correspondent, I’ll be getting science communication training from Neil Andrews (@NeilAndrews) and Dr. Christine Chambers (@DrCChambers). I look forward to improving my communications skills and learning new strategies to share knowledge with diverse audience groups.

During NAPS, I’ll be blogging each day as well as live tweeting on my experiences. I also have the privilege of interviewing Dr. Troels Staehelin Jensen, one of the visiting faculty members for NAPS 2019. Dr. Jensen is a Professor of Neurology at Aarhus University Hospital, Professor of Experimental and Clinical Pain Research at Aarhus University, and Director of the International Diabetic Neuropathy Consortium at Aarhus University in Denmark. At NAPS, Dr. Jensen will be providing a talk on "Risk Factors for the Development of Persistent Pain." Stay tuned for a writeup of his talk as well as an interview with him on his research, career, and thoughts on the future of pain research.

I’m looking forward to a week of fun, pain science, and professional development in Montebello, Quebec. Find me on Twitter (@vader_kyle) and use the hashtag #NAPainSchool to follow along from June 23-28!

Kyle Vader, PhD student, rehabilitation science, Queen’s University, Canada

Whew! It’s just about a week to NAPS. And after a minor (read: not so minor) travel /immigration scare I can now say I’m ready to be a NAPSter! In general, I love meetings, conferences…really, scientific gatherings of any kind. My first real experience at a big science meeting was at the 2018 IASP World Congress on Pain in Boston, USA. Besides all the insightful new concepts and techniques, you get to learn and make new friends from all over the world; I especially love the big-picture reminders I get at these meetings. Listening to talks from experts from different backgrounds in the field really reminds me of the real reason why the work we do is important. Talking with others, getting new ideas or even hearing real patient stories—these are the moments that keep me going. I’ve heard so much about NAPS—from the social media coverage, past student testimonials at my university, and my mentor’s highly encouraging push to apply. So, I’m really excited to be at this year’s NAPS, to meet our faculty, other NAPsters and to fully enjoy my time immersed in science and fun.

I love that the theme of this year’s event, tagged “Biggest Neglected Problems in Pain Research and What To Do About Them?” is so solution oriented. Personally, I always think about how the complexity of pain in and of itself, with its sensory, cognitive and affective dimensions all coming together to make it a really personal experience for each patient, has made pain fairly difficult to model accurately. This has made it more difficult to translate our findings in pre-clinical studies to real-world treatments. But, as with anything, there are always ways to improve and I know I’ll be leaving NAPS with new ideas. I find that exchanging ideas in a more relaxed format than the everyday lab environment can be really mind opening so I know NAPS will be great for that. I look forward to hearing and sharing findings, learning new techniques and gaining a better appreciation of the ones I may already be familiar with. I also look forward to interacting with all the other trainees, many of whom are already doing very interesting work. I see this as my opportunity to form lasting connections with the next generation of pain experts who will continue to move the field forward. Hopefully, we’ll stay in touch, see each other again at future pain conferences, and pick up right where we left off.

Blogging and live-tweeting as a PRF Correspondent will be exciting as well. This will be my first official foray into science communication, so wish me the best!

Titilola "Lola" Akintola, PhD student, University of Maryland, Baltimore, US

Summer Camp for Adults Studying Pain?!? Sign Me Up!

As a graduate student studying pain neuroimaging in humans, I spend most of my time sitting in front of a computer, processing data and running scripts on the terminal. My monitor looks like an ongoing stream of random digits and numbers – kind of like The Matrix, but no, I am not quite entering that virtual reality and there is a purpose behind all the numbers. For someone that spends a lot of time in solitude (sounds gloomy but hopefully current and former graduate students can relate to being in a scientific micro-niche?), the idea of attending a program that provides “a unique educational and networking experience for the next generation of pain researchers” sounds so exciting.

Don’t get me wrong, I love the day-to-day life of research – there are few things in life more rewarding than having the freedom to chase questions that no one knows the answer to and to pursue them with my own creative vision. But the beauty of NAPS is its unique experience that brings together trainees and faculty from all disciplines of the pain field to learn and network intimately. This kind of opportunity is (I think) rare – I get to leave my desk, share my science, and meet like-minded people who care about pain in a more personal and interactive way. With the theme of this year’s NAPS, I am beyond excited to learn about the “Biggest Neglected Problems in Pain Research… and What To Do About Them,” meet the trainees and faculty who are all devoted to improving patient care and pain treatment, as well as enjoy the fun activities that are planned, including the bonfire, sugar shack dinner, and white water rafting (!!). It really does sound like a summer camp, specifically for adults studying pain. So NAPS, here I come! And stay tuned @SarasaTohyama.

Sarasa Tohyama, PhD student, University of Toronto, Canada

The Spiritual, Societal, and Historical Milieu Influencing Pain Perception

He fought down an aching shiver, stared at the lightless void where his hand seemed to remain of its own volition. Memory of pain inhibited every movement. Reason told him he would withdraw a blackened stump from that box.

"Do it!" she snapped.

He jerked his hand from the box, stared at it astonished. Not a mark. No sign of agony on the flesh. He held up the hand, turned it, flexed the fingers.

"Pain by nerve induction," she said. (Herbert, Dune, 9)

I love science fiction. It can often inform science and give a glimpse into how our endless drive for knowledge could shape the world around us. Unlike many animals, humans have an enormous capacity to control our response to noxious, or painful, stimuli. I will often end talks with a note about the Pain Box from Herbert’s science fiction classic Dune [1], which illustrates this point brilliantly while emphasizing other important aspects of pain. The idea of artificially inducing pain highlighted in the above Dune quote has become more widespread—as it is masterfully portrayed with the potentially negative consequences in Black Mirror’s “Black Museum” episode. However, this idea of pain induction, instead of reduction, potentially being useful also points toward a broader discussion that I look forward to having at North American Pain School (NAPS) 2019 related to this year’s “Biggest Neglected Problems in Pain Research … and What To Do About Them” theme: what pain perspectives, management, and research are we overlooking by a focus on eliminating patient pain that is Western-centric in outlook? This theme will be touched on more in the future, but here I will briefly highlight introductory thoughts on two areas: understanding societal and spiritual influences on pain perception along with different historical and non-Western perspectives on pain.

Currently my views of pain are formed from a mix of personal experiences and my basic science, systems neuroscience research into nervous system function [2] using calcium imaging techniques during my PhD in Prof. Mark Schnitzer’s lab [3]. These views have and will benefit from interactions with physicians, patients, and others. Looking over the North American Pain School 2019 program [4], I am encouraged by the Patient Partners and “Ask-A-Patient” sessions. These should provide great opportunities, beyond discussions with those that work in a more clinical setting, to ask about both systematic and anecdotal perspectives on how pain perception varies across those of different socioeconomic and spiritual backgrounds.

The interaction between spiritual views and pain often reminds me of a conversation with a friend who had studied both medicine and theology. He noted that one goal as a physician would be to improve the broader community and spiritual life of patients, both to improve patient outcomes, such as in palliative care settings, as well as to give those at the end of life a more comfortable passage to the next. This view of the interaction of spirituality and pain, the biopsychospiritual model, has been reported on previously and research suggests that certain types of prayer or spirituality can help with pain management [5-7]. While we are unlikely to turn patients into Thích Quảng Đức, a Buddhist monk who famously endured self-immolation by fire, there is an opportunity to discuss in a more comprehensive fashion how greater interactions between clinicians, churches, and other spiritual communities can improve pain management.

Beyond the spiritual is the societal influence on pain. Societal factors are known to play a role in pain perception and reporting [8] and has informed biopsychosocial models of pain [9]. We currently live in an increasingly urbanized society [10] that limits many people’s access to nature [11], losing out on the many associated health benefits. While effective pain management in the clinic is important, this should be complemented by incorporating the wider context of how other aspects of modern life—such as constant agitation due to car and other noises; stress caused by dreary architecture and living spaces along with jobs, advertising, etc.; and lack of deep community connections and support owing to a variety of causes—interact to prevent proper healing, e.g., via stress-induced alterations in body function [9].

For example, within urban planning landmark works such as The Death and Life of Great American Cities [12] and the idea of walkable cities [13] have paved the way toward better understanding the interaction between living spaces, community, and wellbeing that have helped guide redesigning existing and new urban landscapes to improve population health. Throughout NAPS 2019, I would be interested in what faculty and NAPsters would consider to be an appropriate way for pain researchers to interface with government officials, urban planners and architects, community organizers, spiritual leaders, and others to look into ways local and regional communities can integrate ideas from multiple fields to help improve pain management, with additional benefits to other health outcomes. This will be increasingly important as the population ages and larger, planned living spaces are developed.

Lastly, a historical and cross-cultural perspective of the general populace’s view and experience of pain can help us see whether other avenues of treatment are being missed. For example, during the Middle Ages in Europe, the view of death was different than it is now [14-15]. Death was ever-present and this has led to the claim that people back then were better able to cope with death than we are able to today. Great review articles have been written about the changing intellectual and scientific views on pain throughout the ages [16]. However, these should be complemented by more non-academic/clinical histories of evolving cultural perspectives on pain. In addition, more discussion in Western academic institutions should involve how non-Western cultures view, study, and experience pain. Cross-cultural perspectives have been studied before, such as the painful procedures women of the Dugum Dani tribe in New Guinea undergo that are considered natural and thus apparently do not cause as much suffering as might be assumed [17]. A discussion I had with a research scientist who had done acupuncture to reduce back pain highlights this point: they initially went in very skeptical and dismissive of the practice (there are many valid reasons for this [18]), but after experiencing it gained a new perspective, commenting on how their acupuncturist mentioned that in the East any pain during the procedure is not avoided, but embraced. These are only segments of a broader tapestry highlighting differing views of pain across space and time that may prove useful for devising new, holistic pain management strategies.

I am super excited to discuss these thoughts at NAPS 2019 and get perspectives on how we are and can better integrate spiritual, societal, and historical-cultural perspectives into pain research and management. I look forward to sharing the insightful discussions as a PRF-NAPS correspondent (keep updated @syscarut)! Montebello, here we come!

Biafra Ahanonu, PhD, postdoctoral scholar, Stanford University, Stanford, US

References

1. Herbert, F., & Schoenherr, J. (1965). Dune.

2. Quiroga, R. Q., & Panzeri, S. (2009). Extracting information from neuronal populations: information theory and decoding approaches. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(3), 173.

3. Corder, G., Ahanonu, B., Grewe, B. F., Wang, D., Schnitzer, M. J., & Scherrer, G. (2019). An amygdalar neural ensemble that encodes the unpleasantness of pain. Science, 363(6424), 276-281.

4. Mogil, J. (9 June 2019). North American Pain School 2019 Program. Retrieved 16 June 2019 from https://northamericanpainschool.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/NAPS_program_2019.pdf.

5. Weinstein, F., Kapenstein, T., Penn, E., & Richeimer, S. H. (2014). Spirituality assessment and interventions in pain medicine. Practical Pain Management, 14(5).

6. Siddall, P. J., Lovell, M., & MacLeod, R. (2015). Spirituality: what is its role in pain medicine?. Pain Medicine, 16(1), 51-60.

7. Dedeli, O., & Kaptan, G. (2013). Spirituality and religion in pain and pain management. Health psychology research, 1(3).

8. Institute of Medicine. 2011. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13172.

9. Gatchel, R. J., Peng, Y. B., Peters, M. L., Fuchs, P. N., & Turk, D. C. (2007). The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions. Psychological bulletin, 133(4), 581.

10. United Nations. (2018). 2018 revision of world urbanization prospects.

11. Cox, D. T., Hudson, H. L., Shanahan, D. F., Fuller, R. A., & Gaston, K. J. (2017). The rarity of direct experiences of nature in an urban population. Landscape and Urban Planning, 160, 79-84.

12. Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.